Which metaphor will the new U.S. administration base its approach to China on — the sleeping giant, a waking dragon, the sick man of Asia? As President Bush heads into his first meetings with top-level Chinese leaders, it’s very uncertain. He has signaled a hard line on Beijing — an approach that some say could send relations into a deep freeze — but Beijing is so far confidently betting against it.

“In Washington, you hear a lot of tough things said by people who are joining the Bush government,” says Zang Guohua, a longtime Beijing journalist who is now Washington bureau chief for a Taiwan-based TV network. “But when you talk to Chinese officials, they have a different view.”

Zang says officials believe Bush, like his predecessors, will take a softer line on Beijing as they realize the high stakes in the relationship. “In Beijing, they still have a lot of hopes for a friendly Bush presidency once Bush gets a real feel of what he’s dealing with,” Zang said.

China's growing clout

Their confidence is based on real changes in China. Compared even to 1993, when Bill Clinton entered the White House, President Bush faces a far more influential and sophisticated China. It has a massive pool of educated professionals, well-traveled businesspeople, major cities that are peppered with Starbucks, McDonald’s and Gap stores. It has grown explosively and absorbed the lion’s share of foreign investment among developing countries.

It also has in increasingly well-trained and equipped military — a military that could plausibly launch a punishing strike, if it chose, aimed at Taiwan or the United States.

Beijing is demanding that with its new economic clout, and size, it be treated accordingly — as a major player in international organizations and in defense discussions. This year, it will host the regional Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation forum in Shanghai, and it is lobbying hard to play host to the 2008 Olympic Games.

The most important change in the Chinese psyche is the smooth reversion since 1997 of both Hong Kong and Macau to control by Beijing, after a century of colonial rule. The success of these two moves has focused Beijing’s attention on unification with Taiwan, which it sees as completing the consolidation of its rightful empire. Beijing has no goal more important than this one.

Bush suggests otherwise

The signals Bush has sent so far do not bode well for ties with China. He strongly suggested that he would shift U.S. priorities to “allies” in Asia, particularly Japan, and distinguished himself from his predecessor by characterizing China a “competitor” rather than a “strategic partner.” Some cabinet appointments, such as that of former Japan ambassador Richard Armitage as deputy secretary of state have reinforced this shift.

Bush has made statements that in the past would have set off loud alarms in Beijing, including, during his campaign for the presidency, a comment suggesting he would visit Taiwan, something no U.S. president has done since Washington resumed diplomatic ties with Beijing in 1979. A state visit would be viewed as a violation of basic accords between Beijing and Washington that rest on the principal that there is but one China, and Taiwan is merely a part of it.

Even a trip dubbed as “private” by Taiwan President Lee Teng-hui to his alma mater Cornell University in 1995 set off a firestorm between Beijing and Washington, and factored into China’s decision to hold missile tests near Taiwan — an escalation of hostility that alarmed the whole region.

Beijing sorts words and actions

But Bush’s campaign statement didn’t elicit a strong reaction from China. Growing in sophistication, Beijing views political rhetoric coming from Washington with more equanimity than it used to. After all, it witnessed Clinton lobby hard for China’s accession to the World Trade Organization, after initially campaigning against allowing China preferential trade status with the United States. The same president who described the leadership in Zhongnanhai as the “butchers of Beijing,” referring to the 1989 crackdown on Tiananmen Square was gamboling about on the Great Wall seven years later.

In the lead up to Beijing’s first direct contact with the new administration, Prime Minister Zhu Rongji set a conciliatory tone — in sharp contrast to the rhetoric of the past — noting that being called a “competitor” is not necessarily bad. (Perhaps he saw greater respect for China in this designation.) He also suggested that Beijing and Washington could discuss U.S. plans for a national missile defense system, which Beijing has previously opposed as a threat to its own missile deterrent capacity.

Beijing warns on Aegis, but waits

What Beijing awaits is a clear bellwether of President’s Bush’s approach to China — his decision over an upcoming arms deal with Taiwan. If Bush approves a request by Taiwan for four destroyers equipped with the Aegis radar system, Beijing would see it as a fundamental change in the security arrangement and a threat to its most cherished goal: bringing Taiwan back into the fold.

And on this point, China has been very direct. In a speech in Washington, days before meeting President Bush, Vice Premier Qian Qichen warned that the Aegis sale would be a violation of a 1982 agreement under which the United States pledged not to improve the quality or quantity of its weapons sales to Taiwan compared with previous years.

“Just imagine,” Qian said, “China has always stood for peaceful reunification” with Taiwan. The Aegis sale would “change the issue into a military solution,” he added.

“I hate to say it could plunge U.S.-China relations in a deep freeze,” says Jonathan Pollack, Chairman, Strategic Research Department at the Naval War College, referring to the possible Aegis sale. “But it very well could.”

The reasons are both symbolic and strategic. The sale in question could allow Taiwan to link into U.S. Pacific Command systems on short notice, and this would amount, from Beijing’s point of view, to military ties with Taiwan.

Under the Taiwan Relations Act of 1979, the United States is committed to selling weapons to Taiwan for defensive purposes only. These sales must be evaluated and finally approved by the White House. The United States and Taiwan have no formal military ties.

Moreover, the Aegis is powerful enough to detect and deflect up to 100 incoming missiles at a time, which would seriously undermine China’s not-so-subtle pressure on Taiwan to negotiate for reunification. China has about 300 missiles positioned so that they could reach Taiwan. It is said to be adding about 50 per year.

Mixed signals from Washington

Bush’s leaning on the Aegis sale is far from clear, and as always, the debate is secretive.

Some of Bush’s appointments of former Cold warriors suggest he might approve it, while Secretary of State Colin Powell and security adviser Condoleezza Rice are expected to oppose it. Many of the Asia related appointments have yet to be made.

Bush’s right-wing backers have forcefully pointed out that Taiwan has changed too, and say that calls for reevaluation of the relationship. They complain that Clinton’s administration in particular gave Taiwan short shrift even as it has moved to a full-bodied democracy. And they point out that Taiwan, a de facto country, is now led by a president who has openly espoused moves towards official independence.

Taiwan politicians have some reason to hope that they will have a better friend in the White House. They took heart from Bush’s harder line on North Korea recently, and by his stated intent to move closer to Japan, with whom Taiwan is also close.

Behind the scenes contact

Still, China appears relatively sanguine. For one thing, Beijing can pretty safely count on the influence of powerful business interests such as the U.S.-China Business Council — representing companies from AT&T to Boeing and Compaq — to weigh in for Beijing-friendly policies.

And journalist Zang says that defying outward appearance, Chinese officials report that the new administration has quietly contacted Beijing, and that some of the sparring has been less intense privately than in public.

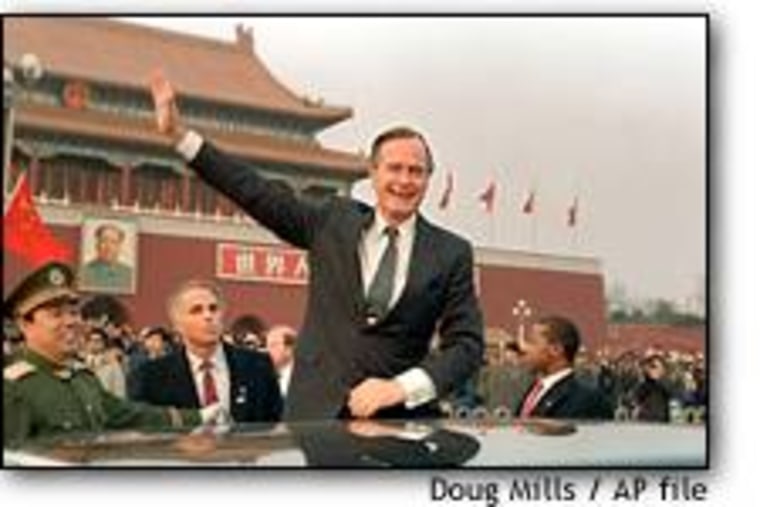

He notes that both the incoming and the outgoing Chinese ambassadors to the United States have made courtesy calls on the senior George Bush in Texas, who they believe can be relied on to influence his son if he moves to far away from the status quo on China.

Even though it was the elder Bush who approved the last significant arms sale to Taiwan — a batch of F-16 fighters — Beijing considers the retired president to be a friend, along with another old diplomatic warrior who engineered President Richard Nixon’s watershed trip to China in 1972. Says Zang: “They believe that if things get really bad, there will always be two people to turn to — (former President) George Bush and Henry Kissinger.”

MSNBC.com’s Kari Huus covers international issues.