In October 1993, when Beijing lost its bid for the 2000 Olympics, it was a bitter moment. Late the night that the decision came, and Sydney was chosen, there were crowds of people clustered on street corners and gathered in Tiananmen Square, and they were angry. Many blamed the United States for the loss. But Beijing’s real problem was its approach — heavy on nationalism and hype, light on substance. For the 2008 bid — now under consideration by a delegation from the International Olympic Committee — it’s clear that China is taking a new tack.

Beijing had much to learn when it launched its first Olympic bid. It’s main mistake in that effort was relying less on practical ways to deal with such a complex event than on nationalistic and political appeals.

The logic of the time: The most populous nation in the world — with one of the oldest culture — simply deserved to win, Chinese officials argued. The implication: China built the Great Wall, so if chosen to host the games, it could certainly put together whatever was necessary by 2000. And there was a political theme woven throughout: If China was awarded the games, it would help propel the agenda China’s reformers, and greater openness of the country.

In Mao's footsteps

China mobilized for the arrival of the International Olympic Committee as only a dictatorship can. The media ran odes to the Olympic spirit, officials put 330,000 children to work cleaning street dividers. Food vendors were ordered out of sight and there were as many as 10 traffic officers at major intersections. Taxi drivers were compelled to learn a few phrases of English, and plaster “Beijing-2000” bumper stickers on their cars, while major factories were ordered to shut down for a few days to clear the smog for the visitors.

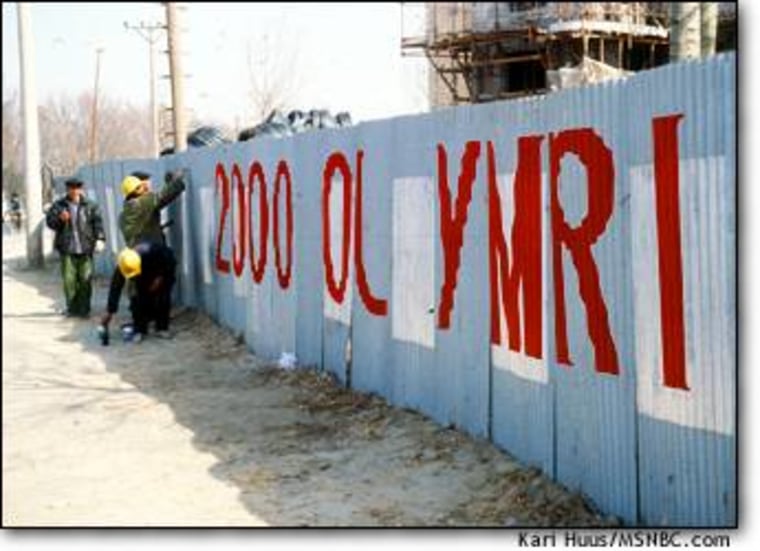

Virtually everyone in the capital was involved in the bid on some level, many conscripted to paint slogans on every available surface. They declared “A more open China awaits the 2000 Olympics” and “Epoch-making games in a legendary city,” replacing the fading slogans of the past — promoting birth control, love for the Communist Party (and its love for the masses), and even some fading anti-Rightist rhetoric.

I remember stopping in my tracks as one small group of slogan painters — factory workers on normal days — painfully copied the slogan that had been penned for them on a slip of paper. “WARMLY WELCOME THE 2000 OLYMRICS.” My contribution to the cause was to point out the error, which they eagerly fixed.

Beijing had convinced many of its own people that it would win the right to host the 2000 Olympics. And after months of being revved up to grab the honors, the disappointment was profound. People stood out on the streets, many clustered around hand-held radios. At first, many people heard the announcement wrong, and started to cheer. Then the reality spread through the crowd like a dark cloud.

It was a period of especially tense relations between the U.S. and China — and many Chinese immediately interpreted the Olympic defeat as just one more sign that the Washington was blocking China from becoming a real player in the world. “Why does the U.S. go out of its way to get into other people’s business?” one bystander asked me, accusingly.

Some Chinese friends suggested I temporarily call myself Canadian, so as not to test the mood of the restive masses. In reality, the worst anti U-S.-backlash I experienced was on a couple of occasions when taxi drivers refused to give me a ride. But even intellectuals berated the United States, or just mourned the defeat, because they believed that a successful bid would boost reforms and force the issue of human rights in China.

New savvy and flash

The problem was, that China didn’t convince the Olympic committee. With or without the U.S. congressional opposition to Beijing’s bid on human rights grounds — an idea that is once again floating in Congress — the IOC needed to justify choosing Beijing, very much a third-world capital in transition, over Sydney, a city with first-rate amenities, marketing and money. It apparently couldn’t.

This time around, Beijing is a front-runner, ahead of competitors Paris, Toronto, Osaka and Istanbul. For one thing, Beijing started this effort with the help of top marketing firms, something it only resorted to late in the game on its earlier bid.

A peek at the Beijing Olympic promotional Web site (http://www.beijing-olympic.org.cn/eindex.shtm) is an indication of just how far the Beijing Olympic Bid Committee has come, in part because of the promotional help. Images of Chinese athletes, cultural sites and daily life flash past, with a tidy index of information on event sites, its vision, related news and features. The site features streaming video, produced by filmmaker Zhang Yimou, a Chinese director of “Raise the Red Lantern” and “Farewell to my Concubine” — movies long admired in Hollywood but generally viewed with suspicion by China’s aging leadership. All things considered, the effort is impressive, and without spelling errors, at least for the most part.

In a demonstration of its Olympic spirit, China made a great show of cleaning up its reputation for doping in international athletic competition. In the 2000 games, it withdrew the famous “Ma Family Army” — a group of women runners who had astonished the world in earlier meets. This time, the special training regime they were supposed to be on was revealed as a mere steroid boost.

It’s a sacrifice for a larger cause. While in the past in China, the gold medal count has been paramount, and a national obsession during the Olympics, China wants these games badly, and staked its national pride on them.

The time intervening has made a huge difference in the city’s capabilities. Since 1993, when Beijing was just coming out of a post-Tiananmen crackdown, reforms have resumed and the country has seen a whopping 8-percent annual growth. Beijing now boasts of 450 four-star hotels. Even if some stretch the definition of “four-star,” there’s no denying the construction of up-market hotels in Beijing has been astonishing. And for what it’s worth, since the opening of Beijing’s first McDonalds in 1992, the city has seen an influx of countless other franchise restaurants and stores, including 55 more McDonald’s.

While China as a whole is still a poor, developing country, what visitors would see in Beijing would be a rapidly emerging international capital buzzing with cell phones of thousands of new entrepreneurs. Many of these same business people also travel freely throughout the region and the world, a dramatic shift from the early 1990s.

Pollution from cars continues to grow, but smog generated by factories is on the decline because Beijing, along with other Chinese cities, has gradually moved industry away from population centers.

And there is no doubt China would roll out the red carpet. The government plans $20 billion in new construction — nearly triple what it was promising eight years ago — to get all the necessary facilities in order. The effort would include highways, subway lines and new facilities — a building spree that would rival that of the Great Wall.

Where past and present merge

One thing that hasn’t changed much since 1993 is the poor human rights record that complicates Beijing’s efforts. Even as the IOC inspection team arrived in Beijing, China sentenced 28-year-old political activist Shan Chengfeng to two years in a labor camp for “disturbing social order.” Her crime — signing a petition urging the IOC to press China to release political prisoners.

Some of the prominent prisoners are long-time dissidents like writer Xu Wenli, released when China was making its last Olympic bid, but since re-arrested on new political charges and sentenced to long terms. And it is unclear how many lesser-known people — possible hundreds — are languishing in prison as a result of China’s recent crackdown on the Falun Gong spiritual movement. This will continue to be awkward for China’s leaders.

But as it pours its experience, money and new-found marketing savvy into the bid for 2008, Beijing will be much harder to resist than in the past, when clumsiness alone was enough to nix its prospects.

Reuters contributed to this story.