In a raid of militant homes in the disputed Kashmir this spring, Indian police came across not a weapons cache, but contraband worth even more — the finest Shahtoosh shawls made from coats of Tibetan antelope. The animal, illegally slaughtered on the Tibetan plateau for its wool is now one of the most endangered creatures in the world. But to these traders, and those down the line, they were more valuable dead than alive: The shawls had a street value of about $400,000.

As environmentalists meet in South Africa this week to discuss sustainable development, it’s clear that something has gone very wrong.

“Since Stockholm (the summit on the environment in 1972), we have passed more than 300 international and regional environmental treaties,” says Durwood Zaelke, director of the Washington-based non-profit International Network for Environmental Compliance and Enforcement Secretariat (INECE). “While that sounds impressive, it masks the tremendous failure to make the law work. The environment continues to deteriorate.”

CITES, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, is one of the most widely accepted conservation treaties, with 160 signatories. Even so, says Zaelke, “We are losing species at an alarming rate despite CITES. ... Enforcement is the exception rather than the rule.”

Zaelke and some of the other experts attending the Johannesburg summit are now focused not as much on new treaties as ways of making the existing treaties work — training judges, inspectors and prosecutors, using new technology, and beefing up networks of concerned citizens, to name a few initiatives.

Some recent cases of animal trafficking give a sense of the scale, and profit potential, of illegal trade in rare animals. To make the 80 Shahtoosh shawls found in the Kashmir, would have required the slaughter of about 240 Tibetan antelope.

In January this year, authorities seized a shipment of 10,000 rare turtles on the way to Hong Kong, where they are considered a delicacy. In the former Soviet Union, the plunder of sturgeon for caviar has driven the species to the brink of extinction, and the continued demand in turn, has caused noticeable pressure on other sturgeon populations in the United States. In a recent study in Brazil researchers estimated that criminals steal an estimated 38 million animals from its tropical forests each year.

Some experts say the illegal trade in animals rivals the $12 billion illegal drug trade, and arms smuggling. Conservatively, others say, it is at least a multi-billion dollar business.

CITES alone is not enough

CITES is a solid treaty, say experts who track animal populations. “It’s hard to say where we would be without it. I think the situation would be a lot worse,” says Craig Hoover, director Traffic, the portion of the World Wildlife Fund that monitors illegal trade in animals. “That said, CITES is only as effective as the countries who join it, and whether they take it seriously.”

Problem one, he says, is that even some countries that have been members since CITES inception still don’t have laws on their books to implement it.

Most African countries — home to many of the rare big game animals — are signatories, for instance, and only a handful has laws to back up the commitment.

Other countries have laws, but don’t have the resources to enforce them. In Indonesia, one official complained to Zaelke that he had 1,200 islands to police for illegal logging. Zaelke recalls: “This official said, ‘I have four employees. Can you help me prioritize?’”

Disarray in the government can also unravel systems to prevent trafficking that were in place. Indonesia may be the poster child for regional chaos as politicians in Jakarta struggle to put in place a democracy in the wake of three decades of rule by a strongman.

But there are other prime examples: The break-up of the former Soviet Union allowed greater autonomy in the regions — but the looser system has also led to the overfishing and near destruction of Caspian sea sturgeon.

And in Madagascar this year, as two candidates claimed the presidency, normal government functioning stalled for months. In the chaos, Hoover says, permits to handle wild animals started finding their way to the hands of business people. “It has been a disaster for wildlife trafficking,” he says.

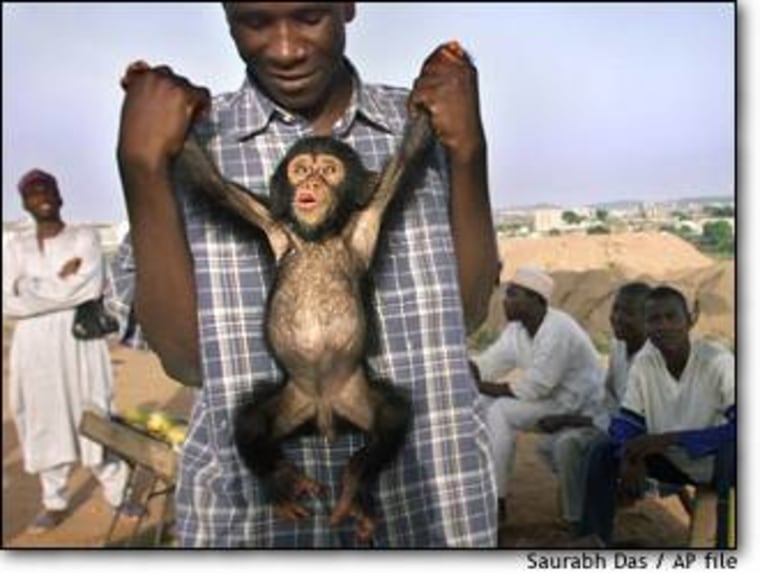

Persistent poverty has increasingly been seen as a major factor in environmental degradation. Indeed, this is one of the central ideas behind the Johannesburg summit — and that any solution needs to address these core problems. No less so in the rapid loss of species. In Africa, for instance, many people survive on “bushmeat” which comes from endangered and abundant species alike.

United States 'loopholes'

But the problem is by no means the province of developing countries alone. The United States, which has some of the toughest rules in place on the import of endangered species, has fewer than 100 Fish and Wildlife inspectors in its ports that process more than 60,000 shipments of wild animals and wild-animal products each year.

And legal loopholes make it difficult to convict traffickers. In a five-year investigation — including 18 months undercover — U.S. Fish and Wildlife agents broke open a case ranging across 20 states that involved trafficking big cats, including leopards, tigers and jaguars, that were killed and sold to the animal parts market for hides, meat, skulls and teeth.

Some were smuggled from abroad, and some were “surplus” animals sold by zoos to the owners of animal parks and roadside shows, people who have USDA licenses to own them.

These owners skirted a law against selling the animals across state lines by claiming to “donate” them, with only cash changing hands. Through a string of “donations” animal park operators, slaughterers, and taxidermists churned up tens of thousands of dollars down the line. Eventually, collectors had the skins and tiger meat was being sold at an exotic meat market in Chicago.

For law enforcement, there were challenges all along the line. “There are way too many people who are licensed as exhibitors and dealers,” says Tim Santel, special agent with U.S. Fish and Wildlife who launched the investigation.

And the “donation” loophole in the U.S. Endangered Species Act “has been exploited in the extreme,” he says. To prove that money was changing hands, the agents were forced to infiltrate the network.

To date, 17 Americans have been indicted in the case, and Santel says more could face charges. Even then, he says, “we only scratched the surface.”

New ideas for old problem

New technology helped get the indictments after DNA testing at a forensics lab in Oregon that specializes in animal identification proved the meat sold at Czimers Game and Seafood market in Chicago to be tiger meat, not lion meat (which can be legally sold). That evidence led to the indictment of market owner Richard Czimer.

The lab has also helped halt the elephant ivory trade. After the sale of elephant tusk was banned, there was a suspiciously sudden surge in the legal trade of “mastodon tusks,” which lab results proved were mostly dyed elephant ivory.

In developed countries, publicity campaigns have had some success in stopping demand for endangered animal products. The Shahtoosh shawl, for instance, was a showcase item on runways in fashion capitals until a public campaign convinced consumers that the product was in fact produced by slaughtering the antelope in huge numbers on the Tibetan Plateau. Some had previously been convinced that the wool was laboriously plucked off trees where the antelope had brushed past.

Zaelke focuses on “capacity building” for officials in developing countries. In conferences with justices and prosecutors, he brings his experience with powerful environmental lobbyists such as Sierra Club. INECE also does practical training for customs officials.

“Customs are the first line of defense. It’s very important for them to be able to recognize when an export permit may be forged, or when the species should have a permit and doesn’t,” says Zaelke. “We are fighting even harder now, with threats of terrorism, to get the attention of customs officials.”

Santel is working with officials in Botswana in techniques for assessing evidence in wildlife trafficking cases.

His organization, INECE has formed an international network of prosecutors called “Green Interpol” which will have access to Interpol resources to investigating environmental crimes, including animal trafficking.

Longer term, however, Zaelke holds out most hope for greater public involvement as watchdogs and as plaintiffs in cases affecting the environment, including wildlife trafficking.

In Brazil, for instance, a non-profit citizen group RENCTAS is recognized as one of the most active forces against wild animal trafficking, by organizing the public into a network of watchdogs to monitor trafficking, including the corrupt officials involved in deals, besides offering training and awareness campaigns.

In India, a new system allows citizens to write a letter complaining of environmental violations which are automatically taken up by the Supreme Court.

One thing that is becoming increasingly clear, Zaelke says, is that conservation cannot be left only to governments.

“Governments as a whole have failed to enforce the law,” he says. “If we had the same level of enforcement in our commercial transactions, the world would be bankrupt.”