President Bush left for Africa on Monday to stress his conviction in the battle against AIDS and his efforts to encourage economic growth, trade and good governance where it is badly needed. The trip, which in many ways echoes the themes of predecessor Bill Clinton, represents a turnaround from 2001, when candidate George Bush made it clear Africa was not really on his radar. Now, with strife in Liberia focusing new attention on the continent, Bush says he wants to send the message to Africa that Americans care. He also has a new motivation to make friends on the continent — oil.

The president's itinerary will allow him to highlight Africa’s success stories while zigzagging around the continent’s most notorious leaders, famine areas and civil wars, not the least of which was war-torn Liberia in the days leading up to his trip.

In Senegal, Bush’s visit will include a stop on Goree Island, once a transit point for West African slaves heading for the United States. For visiting U.S. dignitaries, this stop is practically a mandatory gesture to African-Americans.

In Uganda, which has the best record in Africa for reducing the AIDS infection rate, Bush will visit a hospital for AIDS/HIV patients. It will be an opportunity for him to trumpet the five-year, $15 billion initiative to fight the AIDS epidemic in Africa — $10 billion of it as new funding — that he announced in January.

In Botswana, attention will be focused on the environment and a fledgling U.S. trade initiative.

South Africa and Nigeria

The president’s trip also quite naturally includes South Africa, the continent’s economic powerhouse, and Nigeria, its most populous country.

Many of Bush’s Africa policies follow a path laid out by Clinton. For instance, the idea that American aid and favorable trade deals will go to countries demonstrating good governance is a hand-me-down.

Africa watchers say it is also positive that Bush is making a major trip to long-ignored sub-Saharan Africa, also following a precedent set by Clinton.

“I think it’s positive that he’s traveling to Africa and paying attention to the continent,” says Ian Gary, strategic-issues adviser for Catholic Relief Services, which operates aid and development programs in 22 countries on the continent. “But there are holes in the Bush Africa policy.”

One of those holes, according to Gary and other observers, is the new emphasis placed on Africa as a source of oil — part of a strategy to move the United States away from dependence on Middle Eastern oil, particularly since the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. And development experts say an oil investment boom in Africa, unless properly handled, could do more harm than all the other policies are doing good.

“There is the stated [Bush] policy of wanting to improve African economies, end poverty and conflict but if they don’t push for the transparency of Africa’s oil revenues they will sow the seeds of further poverty and conflict,” Gary says.

The problem is that money going into the oil industry tends to fill the pockets of top politicians who grant access for exploration and drilling. Millions in “signing bonuses” and other concealed perks make a handful of people fabulously rich, but do little for the population at large. Indeed, the inflow of foreign exchange to oil tends to create relatively few jobs and allows countries to import, rather than manufacture, the goods they need. In the end, most developing countries that have oil as their economic mainstay are embroiled in conflict and mired in poverty.

Oil's downside

The one oil state on Bush’s itinerary, Nigeria, is a prime example of how things can go wrong. While the country has since 1999 moved to a democratic system, the process has been rocky and violent. Corruption has diminished little since the days of military rule; in 2002, in Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer for 2003, Nigeria was ranked the second most corrupt place of 102 countries. Meanwhile, despite the fact that Nigeria is a major oil exporter, within the country the cost of oil is so high that siphoning it from pipelines for the black market is a cottage industry. The average Nigerian lives on $1 a day.

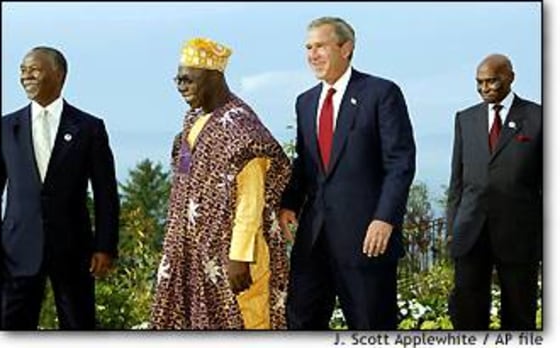

While in Senegal, Bush will meet with the heads of seven West African states — a list that by definition includes tiny countries with large undeveloped oil resources on the Gulf of Guinea. Diplomacy with these countries has ramped up since 2001. Last September, President Bush held an unusual audience at the White House for 10 West African heads of state, including some of the most notorious dictators on the continent.

Among them was Teodoro Obiang Nguema, the leader of Equatorial Guinea, where the United States has also recently opened a new consulate. “He’s one of the worst dictators in Africa,” Gary says. The coastal country is believed to have about 4 billion barrels of oil reserves; U.S.-based ChevronTexaco is the main foreign player, but ExxonMobil and Triton are also deeply involved, making the United States the biggest investor in Equatorial Guinea.

At present, the United States imports about 18 percent of its oil from Africa — most of it from Nigeria, Angola and Gabon. Oil imports from Africa are expected to grow to 25 percent of the total in the coming decade. An anticipated influx of $50 billion in foreign investment will pour into the region, including places where oil reserves are only beginning to be exploited. Chad, Cameroon, Sudan are also oil rich.

West African oil is attractive, too, because it is high quality — almost as good as Middle Eastern oil, experts say — so it requires less refining. Also, transportation from the Gulf of Guinea is relatively inexpensive because it is a direct route that avoids delays and dangers of chokepoints like the Strait of Hormuz.

Non-OPEC nations

Other than Nigeria, the new oil states of Africa are non-OPEC countries, and have shown they are willing to pump oil as fast as they can to reap profits, rather than pace production as OPEC nations do.

Long term, Africa is not the answer for the United States’ energy problem, since Africa’s proven reserves are modest compared to Saudi Arabia’s estimated 260 billion barrels, says Gal Luft, co-director of the Institute for the Analysis of Global Security.

“Some people see [African oil] as a solution, and I see it as a problem,” Luft says. “All you do is deplete the reserves in these countries very fast, only to have a bigger dependency 15 years down the line.”

Luft predicts the United States would end up deploying troops to defend these resources because of the intense civil strife that surrounds them. “It’s sort of a self-fulfilling prophecy that we will have to be there to protect them.”

The Bush administration seeks port access and has discussed sites such as the Gulf of Guinea nation of Sao Tome as possible U.S. military outposts.

For African nations mired in poverty, the impact of oil money coming in could make a huge difference, and would dwarf the amount provided in U.S. and other international aid programs. Africa experts are calling on President Bush to press for transparency on the part of the oil companies as well as the African governments in oil states, putting pressure on those leaders to use the money responsibly.

There is an experiment in accountability in the nation of Chad, where a program run by the World Bank diverts oil revenue into a kind of escrow account, which is then monitored and administered by the World Bank. Its success is subject of debate. Some of the money has certainly gone to the account, but oil experts say Chad has produced more than reported, and used the additional funds to buy weapons to use in its civil war with rebels.

‘Publish what you pay'

A coalition of 75 non-governmental organizations is pressing a proposal called “Publish What You Pay.” It demands global regulation that requires international mining and oil companies to disclose taxes, fees, royalties and other payments to national governments so that leaders would be under pressure to better distribute the income and be accountable.

The White House has shown some interest in an alternative idea, which calls for voluntary disclosure by companies. But under the voluntary system, West African governments — single-party dictatorships of one stripe or another — are unlikely to favor companies that disclose payments. The millions they can make in oil revenue and kickbacks dwarf what is on the table in international and U.S. programs that require good governance.

“If you talk about World Bank programs, the International Monetary Fund, aid from the United States … all this money really pales in comparison to what these rulers can make if they don’t adhere to these rules,” Luft says.

Call to action

The first major test of the Bush administration’s resolve on Africa has arrived. In the run-up to his trip, a conflict between Liberian rebels and the government of Charles Taylor deteriorated into full-scale civil war.

Activists have criticized the Bush administration for being unhelpful in other African conflicts — the fight for the Congo, in particular, where a dozen armies and guerrilla groups vying for land and resources have been embroiled in one of the world’s bloodiest battles for the past five years.

The administration has been more focused on the Sudan, in part because of strong advocacy by U.S. Christian groups pushing for resolution to the Christian-Muslim conflict. There was some hope that Bush might even be present for a peace deal to be signed in Uganda, but those hopes have faded.

The United Nations has called on the Bush administration to provide peacekeepers in Liberia. Although Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld has said Liberia is not of strategic interest to the United States, Bush has said “the people are suffering” and implied that U.S. peacekeepers could be deployed if Taylor is removed.

There are questions, too, about the AIDS fund, which is the seemingly the most ambitious of the Bush Africa initiatives. Bush asked Congress for only a small portion of the funding in 2004, not the $3 billion implied by his announcement earlier this year. The bulk of the remaining funding will have to come in later stages of the program, and skeptics fear it may not happen.

The announcement led American people to believe that “we are more generous and compassionate than we really are,” says Salih Booker, executive director of Africa Action. So far, he says, “it’s not what is happening in Congress, or what the White House intends.”

The organization will be using the Bush trip to draw attention to the need for follow-through. If the funding doesn’t come through, Booker says, “it risks becoming a cruel hoax.”