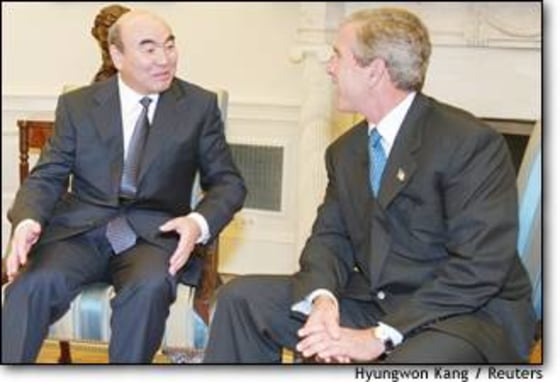

In the club of obscure leaders driven into the limelight by the war on terror, few have been as lucky as Askar Akayev, president of the Republic of Kyrgyzstan. As the Akayev meets with President Bush and other top officials in Washington this week, he enjoys unprecedented attention and support, despite what human rights groups say is a rapidly worsening human rights situation in his home country.

Kyrgyzstan, a small, landlocked Central Asian republic, which became independent in 1991, has few natural resources, and has struggled to reform its post-communist economy. The country is buried in foreign debt and its economy is declining. The government hasn’t managed to build a professional army, a condition more associated with failed states like Somalia.

Kyrgyzstan has also faced real security threats. Islamic extremists with ties to the Taliban in Afghanistan have conducted raids across its border as recently as 2000.

So President Akayev enthusiastically stepped up when the United States came looking for regional support in its war on terrorism after the Sept. 11 attacks. Now, a base built at a former civilian airport at Manas, Kyrgyzstan, is a busy logistical hub supporting the U.S.-led anti-terrorism operations in Afghanistan. There are at least 1,900 troops from eight countries at the base, which accomodates fighter jets, C-130 cargo planes and Boeing KC-135. It was leased to to the U.S. for a year, but president Akayev has expressed flexibility on a possible extension. Kyrgyzstan was the only nation in the region to offer unlimited access for aircraft flying combat as well as humanitarian and search-and- rescue missions.

The Kyrgyz Republic has been “a critical regional partner” in thw war on terrorism, according to J.D. Crouch, assistant secretary of defense for national security.

Kyrgyz cooperation has helped bump up U.S. non-military aid and military aid to the country. Non-military aid jumped from $23.1 million in FY2001 to a total of $42 million in 2002, including annual and supplemental budgets. Military and security assistance has also jumped.

Meanwhile, the United States has also lifted self-imposed restrictions on weapons sales to Kyrgyzstan and its neighbors.

Reputation in doubt

As it happens, the United States is finally focusing on Kyrgyzstan as the country’s reputation falls apart. Once held up as an island of democracy amid a region full of dictators, Kyrgyzstan is sinking into the sea of autocratic rule.

“Over the past year, since Sept. 11 and since the time troops were deployed, the human rights situation has continuously deteriorated,” says Rachel Denber, head of the Europe and Central Asia program at Human Rights Watch. The group is calling on the Bush administration to use its leverage with Akayev to improve the situation.

Akayev, an engineer, rose to prominence through the Kyrgyz Communist Party, emerging as president of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Kyrgyzstan in 1990. After the Soviet Union broke up, he ran unopposed for the presidency of the newly-independent state in 1991, consolidated his power through a referendum in 1994, and then was reelected in 1995.

The real trouble started in 2000, when Akayev ran again, despite a constitutional provision limiting the head of state to two terms. Three of his challengers were brought up on criminal charges and disqualified from the race, including Feliks Kulov, who remains in prison to this day.

In March, protesters took to the streets over the case of a popular member of parliament arrested—an arrest that the U.S. State Department agreed was politically motivated. In a confrontation with the unarmed protesters, police opened fire and killed five people.

Rights groups say that a series of manipulations of the law, including civil and defamation suits have aimed to keep the human rights activists, political opposition and media on the run. Parliamentary powers have been eroded, as more authority has been transfered to the presidency.

In a related trend, the government of Kyrgyzstan is broadly targeting Muslim groups that may present a political challenge.

Among those in the crosshairs in Kyrgyzstan are the Hizb ut-Tahrir, the Party of Liberation—a strict Islamic group that nonetheless preaches nonviolence

But according to Denber, with the exception of Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, which launched the armed incursions into Kyrgyzstan in 1999 and 2000, there are virtually no armed militant groups in Kyrgyzstan.

Human Rights watch says Kyrgyzstan appears to be following the footsteps of the Uzbek government, where thousands of Muslims characterized as extremists have been locked up with little recourse—a process they refer to as “Uzbekification”

Crisis of confidence

As protest and dissatisfaction mount in Kyrgyzstan, observers say the crisis of confidence could become a serious embarrassment for Washington.

“The political fragility in Kyrgyzstan, where we have our largest military presence in the region, has become much more apparent in recent months,” testified Martha Crouch, of the Carnegie Endowment before a Senate foreign relations committee in June. “It is really unclear how the regime of President Akayev will be able to reestablish political trust.”

“If nothing is done—or the United States doesn’t take advantage of this opportunity—then certainly the perception will form in the Kyrgyz public that U.S. is propping up a corrupt government,” warned Denber.

Washington is fighting that interpretation of events. A substantial portion of U.S. non-military aid to Kyrgyzstan is earmarked for building civil society, education and grassroots organizations. According to the State Department it is also alloting money to support of Kyrgyzstan’s parliament, which has acted as something of a check on the power of the president.

The U.S. ambassador to Kyrgyzstan was among the most vocal critics of a law restricting printing press equipment, which the government later repealed. Some of the funding to the country is being used to set up an independent printer for use by independent newspapers and publishers.

But U.S. efforts have “unlikely to keep up with the sharply deteriorating political environment,” Crouch told the Senate committee. She urged lawmakers to aggressively push Akayev to carry through with free and fair elections in 2005.