Some 35,000 Muslim Americans gathered here this weekend for a convention that exhorted them to fight the deterioration of civil liberties, and work to dispel images of Muslims as terrorists and radicals. The three-day convention of the Islamic Society of North America is the largest annual gatherings of Muslims in the country, drawing imams and luminaries from across the United States.

Nearly two years after the Sept. 11 attacks, and the mass arrests and questioning of Muslims that followed, leaders of the community are trying to transform fear into political action, especially as elections approach.

“The Muslim community is at a crossroads,” said Nihad Awad, executive director of the Council on American Islamic Relations. “People are intimidated. They are afraid to organize politically, afraid to give to charity. … We cannot allow this to happen.”

Awad was speaking to a packed session on repealing some provisions of the USA Patriot Act, and organizing to prevent passage of an expanded anti-terrorism bill dubbed Patriot II, a draft of which was leaked to the press by a Justice Department official.

The Patriot Act, which expanded the power of federal agents to search private property and lowered the judicial standard for evidence, was adopted six weeks after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the United States, which were committed by militant Muslims, many from Saudi Arabia.

“When the government says we’re in a war with terrorism for which there is no end … we can’t wait for the war to be over to demand our rights,” said Kit Gage, director of the First Amendment Foundation and National Committee Against Repressive Legislation.

Thousands questioned, arrested

Under the law, thousands of Muslim Americans and Muslim immigrants who are not yet citizens have been questioned or arrested, and an unknown number remain in custody in undisclosed locations. A series of other policies, executive orders and screening methods have also disproportionately affected Muslim Americans.

Patriot Act II, formally called the Domestic Security Enhancement Act of 2003, would further expand the powers of security agents, and allow for the deportation of naturalized American citizens deemed a security risk for their affiliations or political views.

Awad says Muslim Americans need to take up the mantle of civil rights leadership, just as African Americans did three decades earlier. “It may appear we are defending the rights of Muslims, but in reality we are defending the rights of all Americans,” says Awad.

This session and others stressed that Muslims need to know their rights, and assert them. One oft-repeated mantra at the conference: If the FBI knocks, insist on the right to a lawyer before speaking to them. Another: If treated unfairly, at the airport, in the workplace, report these incidents, and fight them.

Speakers urged participants to join movements in cities across the country to resist the Patriot Act. At least 120 cities, as well as the state of Alaska, have passed resolutions saying that they will not enforce the Patriot Act, in a protest of the offending provisions. They also urged Muslims to speak to their local, state and national representatives on their concerns about civil rights.

But rallying this community to political action is difficult. Many Muslim Americans are on the path to citizenship and fear attracting negative attention. And many who are citizens are first generation immigrants who remain focused on hard work and survival.

The younger generation

The most receptive people are the younger generation — people born in the United States who have no immigration issues, says Khurrum Wahid, an attorney with Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem. Wahid, who has worked on some of the more notable post-9/11 cases says, even so, interest waxes and wanes depending on the latest Justice Department movements.

“It’s a two steps forward and one step back scenario,” says Wahid.

“We need an outlet for the voice of moderate Muslims,” said Mohammad Farooq, a professor of economics from Iowa who was attending the conference. “The debate should be dominated by moderates.”

Qasim Shakoor, a 28-year old Yale graduate of Pakistani descent from Youngstown, Ohio, agreed. But he also said he would not be among those speaking out. “I’m afraid to talk. My father tells me to keep my mouth shut,” he said over a plate of dal and rice at the Islamic bazaar attached to the conference. “Ashcroft, Guantanamo Bay, images of Osama bin Laden… All of it creates an atmosphere of fear,” he added. “Most Muslims just want to work hard and make a good life for their families.”

His uncle, Abdul Bari Lateef, a criminal forensics specialist also from Youngstown, has always encouraged his own children to be politically involved, and to get to know the political system. But he too says the post 9/11 atmosphere has given him reason to pause. Coming to such a large gathering of Muslims caused him to “worry like hell” about security.

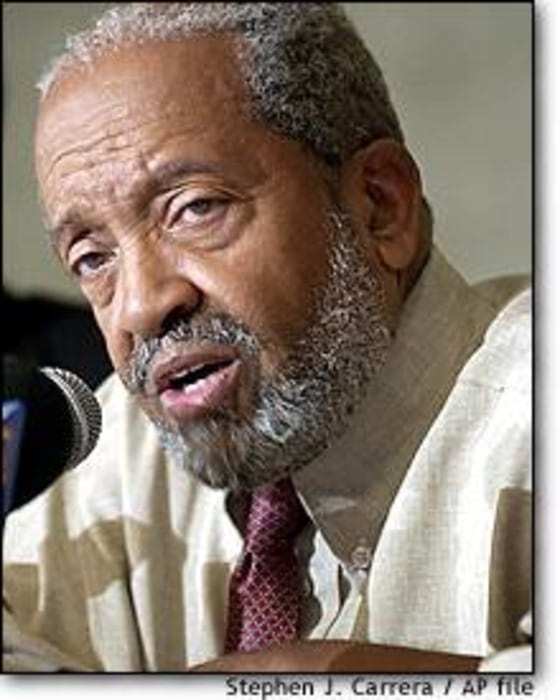

Meanwhile, one of the Islamic Society’s partners, black Muslim leader Imam W. Deen Mohammed, announced his resignation from the American Society of Muslims but pledged to continue working on Muslim issues. His organization represents American black Muslims, while the Islamic Society was founded by immigrant Muslims.

A social event, too

The massive gathering was an opportunity for political evangelism and religious study, but for many people it was equally a social event. Children tagged along with mothers and fathers to large prayer sessions, and then proceeded to a bazaar where hundreds of stalls flogged everything from Islamic children’s books and head scarves to hair restoration potions. One booth sold Internet filtering devices to help parents control the corrupting influences of the Web.

An Islamic film festival ran parallel to the more sober sessions, including comedies geared to the American Muslim experience. There was a loudly announced blood drive under way, and regular sessions teaching CPR. After hours, there were “halal” gatherings for single young men and women to meet.

As the day’s sessions came to a close, many of the head-scarves came off, and the cell phones came out, as the young people arranged their plans for the evening.