There’s one in every family — the conspiracy theorist uncle, certain that the world is run by a secret cabal. Or maybe it’s the dotty aunt who bolts her door with 14 locks, too racked with paranoia to leave the house.

Take a good look, America.

OK. You can put the mirror down now.

This was the year Americans confronted the awful aftermath of 9/11. It gave us time to put the event in context, to assess what we are and how we see ourselves as a nation.

It was the year America became a player in a Pedro Almodóvar film — a Nation on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown.

We made an accommodation with our anxiety, but we did not come to a particularly flattering arrangement.

The face of fear

Americans thought they had fears before 9/11: Kid-eating sharks. Mad cows. Shifty-eyed California congressmen with painted-on grins.

Please.

In the post-9/11 world of 2002, we confronted the reality that some very bad, very resourceful people wanted to kill as many of us as they could. All around them, Americans found, or thought they had found, reasons for suspicion.

Racial and religious profiling became a participant sport, no longer confined to law enforcement. Just ask those Americans who follow the Sikh religion — one completely unrelated to Islam in any form, much less the extremist brand cultivated by the 9/11 hijackers. But Sikh organizations reported hundreds of attacks on their adherents after 9/11, continuing well into 2002 despite a direct appeal from the president for understanding.

Americans went nowhere in droves, most of them scared to travel, the rest annoyed at the security measures imposed on those who did go out and about.

Although they remain much less restrictive than those in countries with long histories as terrorist hot spots, America’s airports became armed fortresses in many people’s eyes, where carrying a nail clipper earned you an appointment with a menacing-looking man in a uniform — only now, he worked for the government, and he carried a gun.

About to land and need to use the lavatory? Tough.

Driving back from a day trip to Canada? Pack a lunch. You’re going to be idling in line at the checkpoint for a good long while.

This Christmas season, dashing through the snow to Grandma’s house in a one-horse, open sleigh is more than a jaunty holiday lyric. It doesn’t sound all that bad. Even if you’re going cross-country.

What's bugging you?

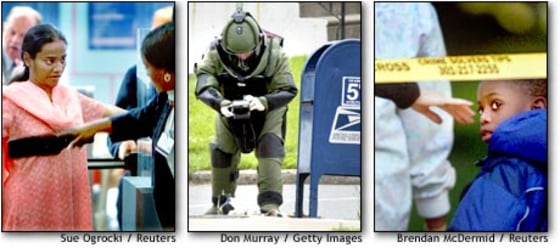

Other, more mundane transactions also took on a Hitchcockian cast. Like going to the mailbox.

First it was anthrax, the germ that made us suspicious of baby powder and Sweet ’n Low. The anthrax letters of late last year have receded from memory, but they continue to have a profound effect on commerce and communications to this day.

Hundreds of thousands of Washington-area residents still can’t be sure your package will get through to them. The capital’s main mail-processing center remains closed, more than a year after some of the anthrax letters were processed there.

Want to send a letter to the editor? At most newspapers and magazines these days, it’s fax or e-mail only, please.

Got a minor infection? Don’t count on getting that antibiotic prescription that worked so well last time. Doctors worried about the efficacy of Cipro warned that continuing overuse of antibiotics could lead to the rapid evolution of resistant bacteria.

Then there were the mail bombs. Forget whether opening a letter could kill you. If you sneezed within a hundred yards of a mailbox, everybody ducked.

By the time he was arrested in May, college student Luke Helder was accused of planting 18 bombs in mailboxes in the Midwest and the Southwest, injuring at least six people. He allegedly was following a pattern that would have reflected a smiley face on the map.

Now it’s smallpox. It’s the most frightening of all, and not just because it’s deadlier. It’s worse because it’s purely theoretical. We know, or thought we knew, where the anthrax would show up. We don’t even know if the smallpox will make an appearance.

So the president got jabbed with a needle carrying a vaccine with some fairly scary risks of its own, to ward off a disease that hasn’t shown itself in three decades and may not even exist at all.

Home, sweet home

But our fear didn’t end with terrorist-related concerns.

Dedicated to never again being caught napping, Americans in 2002 began looking under every rock. They found plenty to recoil from.

White vans and trucks had their day of suspicion. The D.C.-area snipers drove home the reality that any nut with a gun could end your life.

Would the spasm of fear that gripped America during the sniper shootings have been so pronounced if 9/11 had never happened? It’s an unanswerable question. But it didn’t help that the chief suspect turned out to be a convert to a militant form of Islam who allegedly hailed the terrorist attacks.

Amber Alerts joined white vans and blue Caprices in America’s palette of uneasiness. There were actually fewer abductions of children this year than in previous years, but for a while this summer, parents eyed with suspicion any man who roamed within a half-mile of their kids.

Especially if he was a priest.

So America RSVP’d its regrets and stayed home.

Air travel over the summer — prime vacation season — fell a full 22 percent, the Travel Industry Association of America reported. By the time final figures are in, airlines are expected to report an overall drop in passengers of more than 10 percent for the year.

The American Automobile Association said overall travel this holiday season was expected to fall a further 1 percent from the post-Sept. 11 levels of a year ago. Hotels, meanwhile, reported a drop in occupancy of almost 4 percent during the first half of the year.

What were people doing with their time? They were watching sports on television. Attendance at Major League Baseball games fell by more than 6 percent — but TV ratings jumped nearly 15 percent. NFL ratings were also up significantly, by 9 percent through the halfway point of the season.

Still, you couldn’t be too comfortable inside your home. After all, you couldn’t be 100 percent sure you’d have a home. On the heels of the terrorist attacks came an economic slowdown. In truth, it had been brewing for a long time, but it chose a particularly unfortunate moment to begin percolating.

The stock market, already queasy from the wild ride of 2001, began uncontrollably screaming and waving its arms as it barreled down the roller-coaster loop-the-loop. By last week, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was down 16 percent for the year, while the Nasdaq had fallen 30 percent — and those figures included a healthy jump from October.

The unemployment rate reached an eight-year high in April and essentially stayed there the rest of the year.

The technology sector, which was supposed to buttress all things economic, showed no signs of picking itself off the floor. U.S. technology employment fell by almost a half-million in 2002: Sun Microsystems cut its staffing by 11 percent and announced plans for further layoffs next year. IBM slashed 15,600 jobs. Unemployment in Santa Clara County, Calif., home of Silicon Valley, reached 80,000 this year.

The economy cut several business giants down to size. Fifty-four publicly traded companies filed for bankruptcy from May to August. National Steel went under in March. US Airways went bankrupt in August, followed by United Airlines in December.

Then, of course, there were WorldCom and Enron.

Giving Americans the business

In such an environment, when folks are looking closely and anxiously, previous exuberances come out looking more than a little unsavory:

I met him on a Monday and my sheets were spread

At Enron-ron-ron, at Enron-ron.

The lawyers got the truth, but they were trying to shred

At Enron-ron-ron, at Enron-ron.

Oh, when profits dip;

Here’s a little tip:

Form a partnership

With Enron-ron-ron, with Enron-ron.

- The Capitol Steps

WorldCom was shown to have improperly accounted for $9 billion and was forced into bankruptcy. Adelphia Communications’ founder, John J. Rigas, was arrested and charged with conspiring to loot the company of more than $2.5 billion.

And at Tyco International, Chief Executive Dennis Kozlowski was ousted amid reports that he had used company funds for personal extravagances like a $6,000 shower curtain and a life-size ice replica of Michelangelo’s David. Eventually, Kozlowski and Chief Financial Officer Mark Swartz would be charged with 38 felony counts for allegedly stealing $170 million from the company and pocketing $430 million more in tainted stock sales.

For a brief time, rich (or once-rich) men in business suits joined Osama bin Laden and Saddam Hussein in the gallery of scorn as America looked at the cooked books — and sent them back to the kitchen.

Out of the frying pan ...

Speaking of cooking ...

Even food was under suspicion. The New York Times Sunday Magazine knocked dedicated label readers for a loop when it published an article suggesting that years of advice to eat a low-fat, high-carbohydrate diet were all wrong.

Most nutrition experts denounced the idea that fat is your friend, but it was too late. Steakhouses reported record business, and some of them even started dropping lower-fat options from their menus. They stopped selling.

Holy cow. Just what was a poor vegetarian or animal-rights activist supposed to do in the face of the new red-meat mania?

Anthrax, meanwhile, wasn’t the only bug to seize attention in 2002. Every other week, it seemed, diners were being rushed to the hospital in the latest E. coli or listeria outbreak.

Recalls of meat soared to record levels, the Agriculture Department reported. All told, an estimated 79 million illnesses, 300,000 hospitalizations and 5,000 deaths were blamed on food-borne diseases.

But it wasn’t until late in the year that the most frightening food news of all came along. Scientists at Stockholm University announced in April that baking and frying produced extraordinarily high levels of a chemical byproduct called acrylamide — a known carcinogen. The research was deemed so important that the scientists went public with their findings before they had been published in an academic journal.

The Food and Drug Administration called the discovery “worrisome” and ordered expedited studies, because the acrylamide appeared to form in the most common foods — starches like French fries and crackers. And especially bread, now the staff of death.

Finally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention advised doctors this year not to rely on traditional scrubbing before surgery. Alcohol-based gels — similar to the waterless hand-cleaning gels you can buy at the supermarket — did a better job of sterilizing, the CDC found.

“Washing with soap and water was the least effective method” in every study it monitored, the CDC said.

That was 2002. You couldn’t even trust soap.