Ten years ago Colombian farmer Miguel Lucero abandoned his coca crops and replaced them with hearts of palm under a U.N.- sponsored alternative development program. “Although I was happy with my economic situation while I was growing coca, I did not want to see my family in that kind of environment,” Lucero said by phone from his hometown of La Hormiga in Putumayo. “I wanted to raise my children in an honest environment,” he said.

Now Lucero finds himself facing economic disaster, and he is concerned about his wife and six children. He said that his aspiration to send his children to school was shattered after he uprooted his coca crops.

“I do not care about having less food now and not having money for material things such as clothes,” he said. “What hurts me the most is to not be able to provide my children with the education I never had.”

In the past three years, the campaign to encourage alternative development has been stepped up under Plan Colombia. According to the U.S. government, 22,000 families have benefited over the past three years from the alternative development program, which is administered through the U.S. Agency for International Development.

But critics say that it’s too little, too late, and that the government is ignoring the development of the neglected rural hinterland while accepting funding from the United States that modernizes its military.

Coca and poppy, the base material for cocaine and heroin, are considered cash crops by many small farmers like Lucero. They are very profitable because they are easy to maintain and there is always a market, thus avoiding problems such as spoilage. These farmers usually maintain a mix of crops, including food crops for home consumption.

MEETING THE FARMERS

In order to begin alternative projects, the National Plan for Alternative Development (PLANTE), a government run agency in Colombia, meets with small farmers who must sign a formal social pact to voluntarily eradicate their coca or poppy crops.

Then the farmer’s field is marked with Global Positional System equipment that is supposed to prevent it from being sprayed by aerial fumigation while PLANTE provides the seeds for licit crop development.

USAID’s involvement in the five-year Colombian program is estimated to cost $222 million, of which $53 million has been provided since 2000. This year, USAID is spending $122 million on Colombia, of which $60.2 million is for Alternative Development.

U.S. officials maintain that the alternative development program will be successful.

So far, 16,700 hectares (41,200 acres) of illicit crops have been eradicated and 24,500 hectares of licit crops such as rubber, cassava, specialty coffee, and cacao have been planted, according to USAID.

FUMIGATION

The widespread use of aerial fumigation to destroy coca crops has sparked a backlash, and farmer Lucero partly blames it for his own economic situation.

Despite the fact that he has not grown coca in 10 years, his crops were sprayed twice, turning his once healthy harvest “from a vivid green to a dark brown.” It also ruined the grass for the cattle, he said.

“I felt completely destroyed to find myself with nothing from one moment to another for no reason at all,” Lucero added.

Responding to the growing complaints, Colombia’s top court last week ordered the government to suspend spraying of drug crops pending investigations into whether chemicals used are harmful.

The government said it would appeal, describing the herbicide used, glyphosate, as harmless to people. It said glyphosate was one of the most commonly used agricultural chemicals in the world.

“While I’m president and there are drugs, I can’t stop spraying,” President Alvaro Uribe said in a speech last weekend in the village of Orito, also in Putumayo region, where the spraying efforts have been concentrated.

ENFORCEMENT MECHANISM

In the first five months of 2003, the United States helped spray 64,000 hectares of coca, according to officials.

And while it remains a controversial strategy, Adolfo Franco, the USAID assistant administrator of the Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean, said that “without it, it would not be possible to conduct alternative development.” The fumigation was an “enforcement mechanism,” he said.

According to Franco, if legal crops are sprayed, it is usually for one of two reasons. First, some farmers plant licit crops next to illicit crops. For example, they might plant three rows of hearts of palm next to one row of coca.

Second, “there might be a mistake here and there.” He noted that there is compensation for those who are mistakenly sprayed.

The General Accounting Office reported in January of 2002 that alternative development was not having much luck. But Franco said the study was conducted under the previous administration of Andres Pastrana when the procedure to manually eradicate illicit crops was much different.

He said that under Pastrana 37,000 “pacts” were signed between farmers and the government. But once the pact was signed, the farmer was paid and was not checked on to confirm the coca wasn’t being re-cultivated. Franco added that Pastrana’s suspension of aerial fumigation did not help the situation either.

DIFFERENT VIEWS

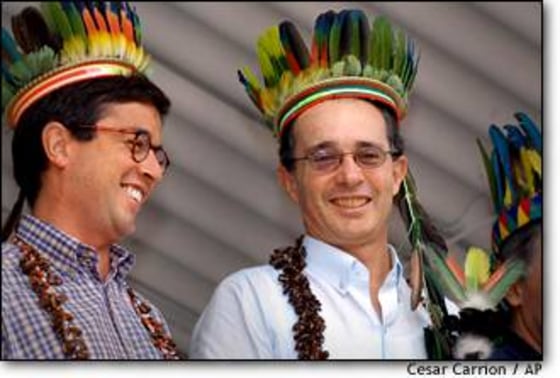

Colombia’s ambassador the United States, Luis Alberto Moreno, downplayed criticism of the fumigation, saying that the government is willing to compensate farmers for any damage caused. And he said that a host of job-creation, alternative development programs are working “tremendously well.”

International and Comparative Studies professor Bruce M. Bagley from the University of Miami is not as optimistic.

“Replanting in previously sprayed fields is taking place at an accelerated pace, particularly in light of the under-funded, deficient, and often corrupt management of Colombia’s alternative development programs in eradication zones,” he said.

In addition, “the intensification of guerrilla and paramilitary violence in many regions of the Colombian countryside during the Uribe administration greatly complicates the execution of crop eradication and alternative development plans in key regions of the country.”

For Lucero, his biggest fear right now is that his children be swept by one of Colombia’s insurgent groups.

His children usually try to find work for the day at nearby farms, but he fears that his children’s lack of education and work opportunities will lead them join the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia or the paramilitary group known as the United Self-Defense Forces.

“If one of my children joins one of the insurgent groups, the rival group will look for revenge and kill the entire family. When I used to cultivate coca, I did not have that fear.”

(Carmen Sesin is an assignment editor for NBC News.)