They flock to the United States every March, Irish politicians of all stripes eager to soak in the seasonal goodwill. But this year’s St. Patrick’s Day festivities for Sinn Fein, the political ally of the IRA, have been clouded by allegations of links between the IRA and leftist rebels in Colombia.

What three Irishmen were doing in Colombia last year has been disputed, as have many of the allegations that have emerged since they were arrested at Bogota’s airport last August.

But what is beyond doubt is that the three Irish citizens, one of whom represented Sinn Fein in Cuba, are stuck in a Bogota jail, charged with helping to train guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, or FARC, designated by the U.S. State Department as a terrorist organization.

In the wake of President Bush’s war on terrorism following the Sept. 11 attacks on the United States, it’s an association that is awkward, at the very least, for Sinn Fein.

The three — Niall Connolly, Jim Monaghan and Martin McCauley — have rejected the charges, saying they visited rebel-held territory in Colombia to study peace negotiations. Ironically, the Colombian government has since moved troops back into the territory after peace talks with the rebels collapsed in February.

The IRA also denied that the three were representing the organization, which declared a cease-fire in its own battle in Northern Ireland in 1997. Meantime, a has been launched in Ireland to gain their freedom.

WASHINGTON PROBE

But in Washington, the House Foreign Relations Committee, under the auspices of Rep. Henry Hyde, R-Ill., has opened an investigation into the arrests following a call from another House member, Rep. Bill Delahunt, D-Mass., for an examination into the veracity of the charges.

“It seems to us that it’s in our national interest to understand if these things are related or not,” Delahunt’s spokesman, Steve Schwadron, said.

The committee members are awaiting the result of the probe to see whether it’s appropriate to hold hearings, Schwadron said.

The United States remains concerned. “It is not a continuing relationship, but it’s not a one-time deal either,” one senior U.S. official said, referring to IRA-rebel relations. “In short, don’t think of it as an organization-to-organization relationship, but an individual-to-individual relationship that was forged a while back.”

The Irish government, which has offered consular services to the three being held in Colombia, has remained mum on the allegations, although one official, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said the charges were an embarrassment that “could complicate the peace process.”

GOOD FRIDAY AGREEMENT

Above all, it’s the peace process in Northern Ireland that concerns the Irish and British governments, and the political parties in the British province.

Since former Senate leader George Mitchell shepherded the parties toward accepting the landmark Good Friday Agreement on April 10, 1998, all sides have looked to Washington to stay involved in resolving the conflict.

After the IRA cease-fire, the agreement set up a multiparty government in Northern Ireland that included the first-ever participation of Sinn Fein.

Since then, the White House has stayed involved in the Irish peace process. Former President Clinton was notable for his interest in resolving the conflict, while the Bush administration has taken a more hands-off stance, although the Irish leaders insist Washington still plays a key role.

”[Bush] is absolutely helpful to us,” Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern said Wednesday at a pre-St. Patrick’s Day reception in Washington.

ADMINISTRATION’S ANGER

The administration’s point person on Northern Ireland is Ambassador Richard Haass, the State Department’s director of policy planning.

He was furious after the three men were arrested in Colombia, telling Sinn Fein at the time that the development was very damaging.

“They were not there for their vacations, they were not there for an exchange of view on negotiation techniques in the peace process, but for discussions with FARC on matters that come under the rubric of terrorism,” he said on Sept. 18. In the immediate aftermath of the arrests, Sinn Fein President Gerry Adams denied any links to the arrested men. In October, however, he acknowledged that Connolly did represent the party in Havana, but said it was without his authorization or knowledge.

Cuban officials said Connolly represented Sinn Fein in Havana and that he left the country last April.

The two other men had past convictions for IRA activity. After their arrests, Sinn Fein’s rivals in the Protestant parties of Northern Ireland pounced on the news, asserting that it exposed the terrorist links of the party.

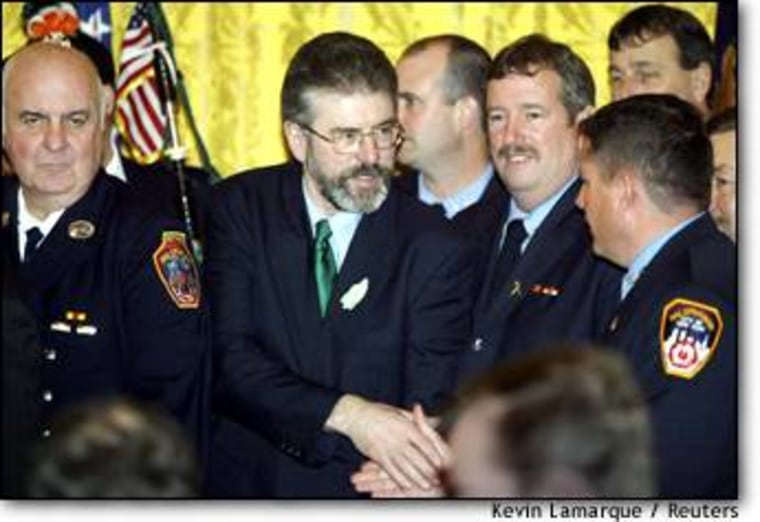

But Washington has refused to isolate Sinn Fein. Haass met with Adams this week, as did Bush, who invited the leaders of the main political parties in Northern Ireland to the White House.

On Thursday, Haass said there was progress toward peace but “I don’t think we’ve reached the positive point of no return where the process is so rooted that it could not unravel.”

As for the Colombian connection, he said, “We have zero tolerance for any support of the FARC by the IRA or anyone else. It’s not a popular insurgency but a bunch of drug-running terrorists trying to disrupt a democracy.”

FRIENDS OF SINN FEIN

Sinn Fein has come a long way in the United States over the past decade.

Adams was only first granted a visa to enter the United States in 1994, after he led his party into a dialogue with the Irish and British governments and the main political parties in the province.

Now Sinn Fein has expanded its political base, becoming the only party in Ireland with representatives in the Dublin, Belfast and London parliaments.

Acceptance in Washington has helped, especially for tapping the resources of sympathetic Irish Americans.

According to Justice Department records, the party’s fund-raising arm, Friends of Sinn Fein, has raised more than $2.5 million since 1997.

Rita O’Hare, Sinn Fein’s representative in Washington, said there has been no drop in contact between the party and the U.S. administration or with Irish-American supporters.

She described the reception of the Sinn Fein leaders this week as “very warm.” As for the Colombia arrests, “it doesn’t figure with Irish Americans or the people in Washington,” she said on Friday.

ADAMS’ EFFECT

For Rep. Peter King, R-N.Y., who has long maintained an interest in Irish affairs, Sinn Fein remains an important force in the Irish peace-making process.

He said Adams has established his credibility with U.S. administrations, currency that has helped Sinn Fein overcome the Colombia controversy.

“I was outraged when [the three men] were found in Colombia; it was disgraceful,” King said. “I’ve had long conversations with [Sinn Fein’s] Martin McGuinness and Gerry Adams about it and they were as angry as I was,” he said. “They also said they’ve received assurances from the IRA that it won’t happen again.”

McGuinness is a Sinn Fein member of the British parliament and minister of education in the current Northern Ireland government.

King remains concerned by the allegations that the Irish republican movement was involved with Colombian rebels, but he said he has seen no evidence that the IRA had sanctioned their presence.

(NBC’s Robert Windrem in New York and Mary Murray in Havana contributed to this report.)