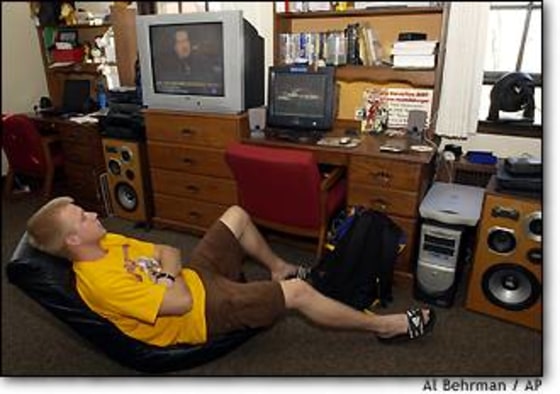

Steve Leslie’s dorm room at Miami University has 20 plugs sprouting from the walls. They power a color TV, stereo, compact disc and DVD players, video game player, desktop computer and laptop, printer, scanner, refrigerator, microwave and two fans. Then there are rechargers for a cell phone, hand-held computer, camera, electric razor and toothbrush.

“I just kept adding stuff,” said Leslie, 20, a junior who shares the room with another student. “I fill up my car and my dad’s truck. Some of the bigger stuff, like the speakers, have to wait for the second trip.”

Today’s collegians are part of a generation raised on electronics, and colleges are having no choice but to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to upgrade electrical systems. Often, the upgrade costs are getting passed on to parents and students in the form of higher fees.

“It looks like Circuit City in some of those rooms,” said Dan Bertsos, director of residence services at Wright State University near Dayton.

New and renovated dorms at Texas Christian University in Fort Worth are being wired to handle the increasing load.

“Kids used to come to college with an AM radio and an electric razor. Now they arrive with every electronic device there is,” said Roger Fisher, director of residential services. “They come to campus in a U-Haul, and Dad follows in a Suburban.”

The average freshman at Miami University takes 18 appliances to campus, according to a March survey by the school.

As part of a $7 million renovation of one dorm, Ogden Hall, the university spent $212,548 in 2000 to add building substations, electrical distribution panels and electrical outlets. The 7,000 students who live on campus pay an extra $100 a year in housing fees to cover the renovation costs.

“These days the students’ lives are quite changed. They need more appliances,” said Takashi Kawai, a 64-year-old Dayton-area man whose son lives in a dorm at Miami.

In a renovation a few years ago, Wright State doubled to four the number of electrical outlets in each of the 162 rooms at Hamilton Hall, increased the number of circuit breakers, installed new electrical-switch gear and rewired fuse boxes and student rooms. The cost was about $500,000, or $1,000 per student.

At Penn State University, electrical consumption in October was 33 million kilowatt hours, up from 27 million in October 1996. The school’s electric bill is about $1 million a month. Paul Ruskin, with the university’s physical-plant office, said power use by the 13,000 student residents contributed to the increase.

Some officials say higher energy costs, campus expansions, lighting and the addition of computer labs and other energy-eating facilities are more to blame for increased power demand than student appliances.

And upgrading electrical systems in new and renovated dorms is often required by law under newer, more demanding building safety codes.

Andrew Matthews, of the Association of College and University Housing Officers-International, said many dorms were built in the 1950s and 1960s and don’t have the electrical capacity for power-dependent students.

The higher amp load has some schools setting limits and conserving.

The University of Dayton had to stop installing air conditioners in the dorm rooms of students who requested them for such things as allergies and asthma. Craig Schmitt, executive director of residential services, said the school will be able to accommodate those students next fall in a new, air-conditioned dorm.

Miami University has been replacing incandescent lights around campus with more efficient fluorescent ones.

But conservation alone is oftentimes not enough.

Maryville College in Maryville, Tenn., decided to tear down one residence hall last year and build a new dorm at a cost of $7 million.

“If too many women turned on their hair dryers in the morning, the circuit breakers would blow. That was happening daily,” said Bill Seymour, vice president and dean of students.