The latest efforts to contact a British-led mission to Mars from its orbiting mother ship failed Wednesday, compounding fears that the Beagle 2 probe crashed during a Christmas Day touchdown.

Gloom surrounding the first all-European mission to Mars contrasts with the joy at NASA, whose robotic explorer Spirit safely landed on the Red Planet during the weekend and has transmitted high-definition pictures in the last few days.

“We did not get a signal from the surface of Mars, but this is not the end of the story — we have more shots to play,” the European Space Agency’s David Southwood said.

“It is a setback and it makes me feel very sad,” he added.

Disappointment at Beagle HQ

Engineers and scientists at the Beagle HQ in London hung their heads after the announcement.

“We hope we’ll get the dog to come back to the kennel,” said a defeated-looking Colin Pillinger, who heads the project. “We must play until the final whistle.”

Although nothing has been heard from the 75-pound (34-kilogram) probe since its attempted landing, scientists say they have not given up and will make further attempts to talk to it.

Project scientists have pinned their hopes on contacting the lander, which is designed to hunt for evidence of life on Mars, on its orbiting mother ship, the Mars Express.

But the Express’s first pass, just 220 miles (350 kilometers) above the probe’s landing site, near the planet’s equator, resulted only in a worrying silence.

Future opportunities

The Express will pass over the landing site again on Jan. 8, 9 and 10 for about five to eight minutes each time. If those attempts fail, it passes again on the 12th and 14th. Pillinger said the absolute last attempt would be made in February.

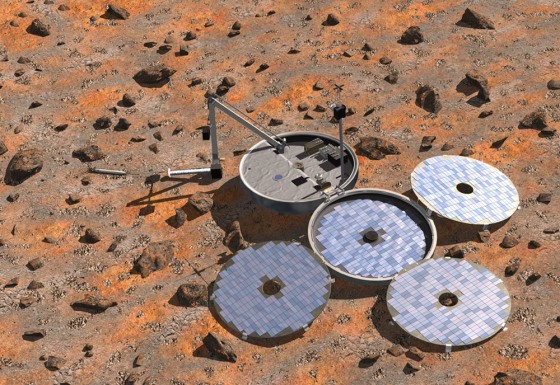

Earlier attempts by radio telescopes and NASA’s Mars Odyssey orbiter to contact Beagle 2, a saucer-shaped probe about the size of an open umbrella, also failed.

Beagle 2, launched last June, is packed with sophisticated instruments designed to take samples from the Martian surface. At its heart is a mass spectrometer used to measure the mass and abundance of atoms and molecules on planetary surfaces.

It was named after the ship that British naturalist Charles Darwin took to gather the data that led to his groundbreaking 19th-century theories of evolution.