India's Mr. Clean has finally been pulled down into the muck of local politics.

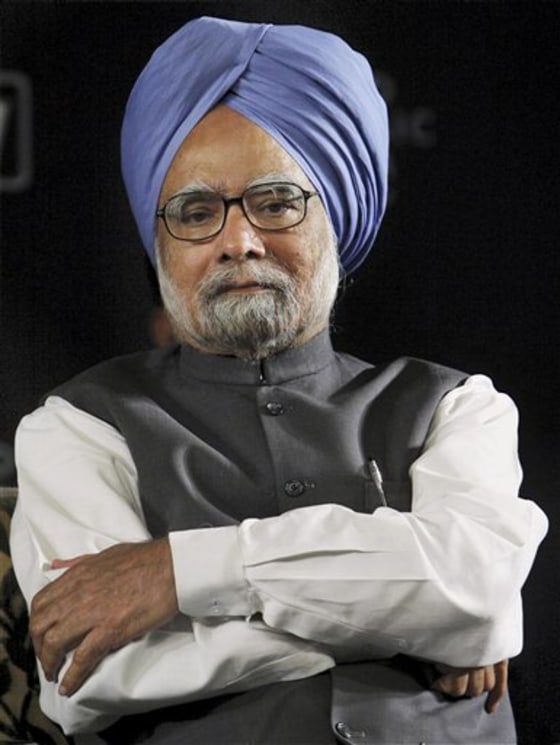

Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, the blue-turbaned economist credited with unleashing India's explosive growth, stands accused of dragging his heels while one of his government ministers presided over a telecommunications scandal that cost the country billions of dollars.

The Supreme Court has issued an unprecedented rebuke to the prime minister and is demanding his government explain itself. The opposition has paralyzed parliament in protest.

While there is no suggestion Singh benefited personally from the scandal, his reputation as a rare leader untainted by India's crass political dealmaking has taken a serious hit.

"A fortnight ago, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh was the toast of the nation," The Asian Age newspaper said. "Today, however, he is faced with what could well be India's own Watergate."

The government, which has denied wrongdoing, is taking the accusations seriously enough to send the attorney general himself to represent Singh at a Supreme Court hearing scheduled for Tuesday.

And Singh promised to get to the bottom of what could be the costliest political scandal in India's history.

"There should be no doubt in anyone's mind that if any wrong thing has been done by anybody, he or she will be brought to book," he said Saturday.

The allegations concern the 2008 sale of second-generation, or 2G, cellular licenses in a bewildering process run by then-Telecoms Minister Andimuthu Raja with ever-changing rules that raised eyebrows even at the time. The sale netted India 124 billion rupees ($2.7 billion), an amount that seemed absurdly low after an auction of 3G licenses this May raised 677 billion rupees ($14.6 billion).

In a report issued last week, the state auditor general said the 2G sale was run "in an arbitrary, unfair and inequitable manner," that violated Singh's wishes for a transparent bidding process and cost the government as much as $36 billion. Many of the 122 licenses were given to "ineligible applicants" who then quickly sold their stakes at a high premium.

Despite persistent questions about his conduct, and an ongoing probe into the sale by the Central Bureau of Investigation, Raja continued to serve as Singh's telecoms minister and was again appointed to the position last year after the ruling Congress Party and its coalition partners won re-election.

The Supreme Court has demanded Singh explain why he took more than a year to answer parliamentary demands to investigate Raja, who was forced to resign last week.

"The allegation is not that (Singh) is a crook, but that he is the night watchman that stood idly by while others robbed the place blind," said Vir Sanghvi, editorial director of the Hindustan Times newspaper.

The scandal flared as Congress and the government were putting out other fires.

Earlier this month, the party forced out Maharashtra Chief Minister Ashok Chavan amid revelations that his relatives and other officials received deeply discounted homes in a Mumbai apartment building meant to house war veterans and widows. It also forced Suresh Kalmadi to resign his leadership position in the party amid the swirl of scandals surrounding India's recent hosting of the Commonwealth Games, which he organized.

In a sign of how pervasive political corruption is here, the opposition Bharatiya Janata Party, which has frozen parliament for nearly two weeks demanding an all-party investigation into Raja's conduct, is itself fighting off allegations one of its top officials sold state land for a pittance to his children.

The 78-year-old Singh, an Oxford-educated economist who runs the country with the air of a genial, though not particularly exciting, university professor, was supposed to be above all this.

He is credited with bringing India out of the economic dark ages when, as finance minister in 1991, he repealed a blanket of regulations that was smothering business here.

A rarity among politicians, Singh expressed no great political ambitions. So when Italian-born Sonia Gandhi, former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's widow, led Congress to electoral victory in 2004 amid a controversy over her foreign roots, she tapped him as her partner in a unique experiment. He would run the government; she would tame the messy world of party politics.

The 2G scandal has shown how difficult it is to separate politics from governance.

The Congress Party resisted dumping Raja — who denies wrongdoing — because he belonged to its important Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam coalition partner, which demanded he retain the post. While the loss of that party's 18 seats would not have brought down the government, it would have left it with a narrower majority more prone to the whims of other coalition partners.

Yet retaining Raja for as long as it did, further tarred Singh and his government.

Though there have been quiet murmurs Singh might have to take the fall and resign, or that he could simply grow so fed up with the accusations that he might decide on his own to quit, such a move remained unlikely.

Congress has rallied behind the prime minister and even his critics continued to describe him as a man of deep personal integrity.

Subramanian Swamy, the opposition lawmaker who filed the Supreme Court case against Singh, praised the prime minister as "decent" and "upright" and said there was no suggestion Singh made any money off the scam.

"Any demand for his resignation is not justified at the moment," he said.

That could change if Singh does not take swift action to clean up the mess, he said.