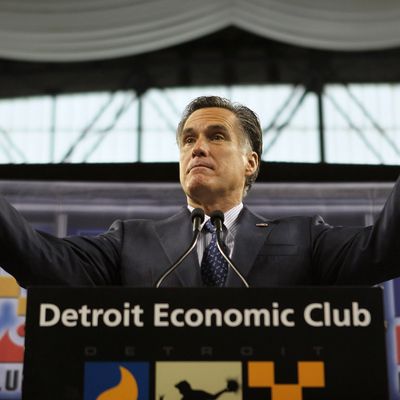

News reports about Mitt Romney’s economic plan last week focused on the cavernous void in which it was held, and brushed off the substance of the remarks. But Romney’s new economic plan this week is highly significant. It signals that the era of Republican fiscal conservatism will come to an end if he is elected.

We should not be surprised. Since Ronald Reagan, budget deficits have been something Republicans talk about in fervent and often apocalyptic tones when there’s a Democrat in the White House. Many people mistook the latest upsurge in Republican deficit-phobia, coupled with debt-themed Tea Party activism, as a lasting change. It was only a temporal one, and as Romney’s new economic theme shows, it is bound to come to an end if he takes office.

Romney is proposing a 20 percent across-the-board tax cut, to be paid for by unspecified spending cuts, unspecified reductions in tax deductions, and — crucially — “economic growth.” Overjoyed conservatives, who until now had been flaying Romney for his insufficient commitment to the cause of supply-side economics, are now displaying the love they had been withholding. The Wall Street Journal editorial page and the Washington Examiner bestow upon Romney the sacred appellation of Reaganism. Reagan, of course, was not what you would call a deficit-slayer. Neither was George W. Bush, who also pursued a Reagan-esque budget vision. Romney is likewise signaling that, should he take office, the emphasis will turn away from deficits and toward “growth,” defined as minimizing tax rates for the rich.

The key tell here is his embrace of “dynamic scoring.” This is a longtime fixation for Republicans, and understanding it helps understand the import of Romney’s latest move. The core is a reasonable-sounding proposition that, when measuring the cost of legislation, budget agencies ought to take account of their effect on economic growth. A plan that would facilitate growth would result in higher tax revenue and thus smaller deficits. In theory, budget agencies could take this into account. A corollary is that, all things being equal, lower marginal tax rates will result in higher economic growth than higher tax rates.

However, all sorts of unpleasant complications intercede. The Congressional Budget Office has trouble accounting for even fairly simple budget projections because the political assumptions are impossible to nail down. Indeed, the CBO keeps two sets of books, one scoring what the law saws Congress will do, and another attempting to guess what Congress actually will do. The tax debate aggravates the problem substantially. Romney’s tax plan, like Bush’s tax plan and Reagan’s tax plan, provides for large up-front marginal tax cuts, combined with theoretical future offsets to limit the fiscal damage. Whether those plans should be scored to increase growth or decrease growth depends not only on how much weight to assign the benefits of lower taxes, which is itself a highly controversial subject among economists, but also whether the magic asterisks will ever materialize.

In practice, “dynamic scoring” metastasizes itself as a demand by Republicans that they not have to provide any offsets for the cost of their debt-financed tax cuts, because those tax cuts putatively increase growth. And those assumptions in turn hinge upon wildly and even hilariously selective readings of the economics literature and recent history. Here’s the Journal cheerleading for Romney’s embrace of “dynamic scoring”:

The Romney campaign is also shrewd to say it will assume some dynamic revenue feedback from his marginal-rate cuts. This does not mean that the tax cuts will entirely “pay for themselves” right away. It does mean that it can safely assume that his proposal would recapture about one-third of the revenue loss from the rate reductions through more investment and economic growth.

That’s a defensible and conservative estimate based on historical experience with rate reductions. Tax revenues soared after the Reagan 1981 tax cuts (the Gipper cut rates across the board by 25%) and the Bush 2003 rate reductions. The 2003 investment tax cut was expected to lose revenue, but the gain in jobs and business activity produced $786 billion more in revenue from 2003-2007.

Ask yourself a question: If the 2003 tax cuts produced so much higher revenue through 2007, why did we get rid of them? The answer, of course, is that we didn’t. They’re still in effect. After 2007, revenue fell off a cliff. Now, revenue fell off a cliff because the economy collapsed, which isn’t the fault of the tax cuts. But it also rose after 2003 because the economy was on an upswing, which was also not the responsibility of the tax cuts. The Journal is displaying here a basic supply-side method, which involves selectively accounting for the state of the economy. For decades they have argued for the benefits of the 1981 Reagan tax cuts by starting their timeline at 1982, which gives the tax cuts all the benefits of the business cycle rise from the 1982 recession without any of the responsibility for the plunge into it. The same technique is at work in their pretense that the Bush tax cuts somehow ended in 2007.

The Republicans demanding dynamic scoring — even the most respectable economists they could find to ally themselves with the cause — all insisted that Bill Clinton’s tax hike would bring in much less revenue than the “static scoring” estimated, by tamping down the incentive of “job creators.” They likewise insisted that Bush’s 2001 and 2003 tax hikes would bring in much more revenue than forecast through the same dynamic in reverse. Both predictions proved fantastically incorrect. (William Gale of the Brookings Institution estimated that the Bush tax cuts overall dampened economic growth slightly.)

Supply-side economics is a theology immune from real-world revision. The significance of Romney’s announcement is that he is allying himself wholesale with the supply-side worldview. He is embracing the Republican governing doctrine of regressive debt-financed tax cuts. Spending cuts would be nice, but tax cuts for the rich are essential. If Romney wins, the agenda will increasingly come to focus on “growth,” and his party’s monomania with debt will be increasingly quaint.