President Obama’s message on the economy has been a delicate balance between noting that things have gotten better but acknowledging that they haven’t gotten better enough. The goal of his press conference was to shift the balance from the former toward the latter. A month ago, Obama was running ads that sounded almost chipper. Now, in the wake of a terrible jobs report and looming Euro-disaster, he wants to remind everybody that he has a plan to improve the economy and Republicans are blocking it.

Instead he delivered a soundbite, instantly seized upon by Republicans and political reporters, that seems to transmit the opposite of that intended message. That soundbite is “the private sector is doing fine.” Republicans are already blasting it out in e-mails and tweets, and the line will no doubt be repeated on Republican campaign ads between now and November. Obama’s attempt to recalibrate his message away from “it’s getting better” to “it’s still not good enough” wound up giving Republicans a line to present him as arguing for just the opposite.

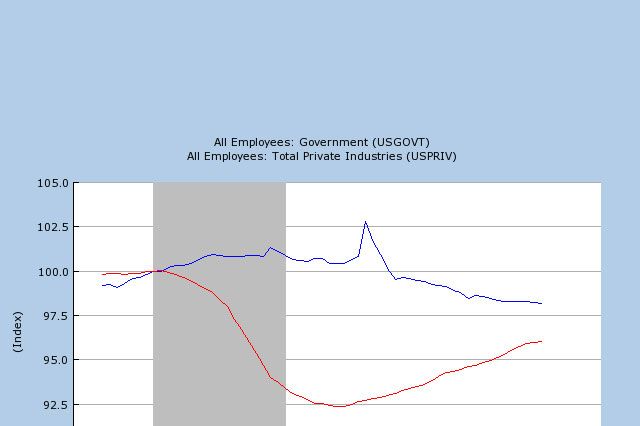

Obama uttered that line in support of his contention that the economy is not fine, and that the Republican Congress ought to stop blocking his jobs program. Obama’s argument is that private sector jobs have grown steadily, but overall job growth has been held back by continuous cuts in government employment (which has dragged down private sector growth as well):

We’ve created 4.3 million jobs over the past 27 months. Over 800,000 just this year alone. The private sector is doing fine. Where we’re seeing problems is with state and local government, often with cuts initiated by governors or mayors who are not getting the kind of help they’re accustomed to from the federal government.

This is true:

The upward-sloping red line is private sector employment, and the downward-sloping blue line is government employment. Obama’s jobs plan is to spend money building public infrastructure and rehiring laid-off state and local employees. Macroeconomic Advisers estimates that Obama’s plan would add more than a million jobs, a calculation that is broadly in line with other private sector estimates.

Republicans in Congress oppose Obama’s jobs plan and utterly deny the consensus beliefs of the macroeconomic industry. The Republican line is that, even in current conditions of mass unemployment, zero interest rates and low inflation, higher short-term deficits harm the economy rather than help it. Republicans embraced this unorthodox line of thinking suddenly, after maintaining the opposite when their party held the White House.

I used to reject the accusation that Republicans reversed their thinking out of a conscious decision to sabotage the economy in order to regain power. I tend to think of the human mind as more malleable than that, with people first grasping their self-interest and then persuading themselves to actually believe it, so that Republicans were walking around in the grips of a genuine fervor for obscure Austrian economic doctrines.

I was shaken of that belief not long ago, when Mitt Romney said off the cuff that cutting spending in his first year would retard the recovery. You would think at least some Republicans would raise a cry of outrage over their nominee’s casual dismissal of the bedrock assumptions that have driven Republican economic policy making for the last three years. Conservatives have not been shy of holding Romney’s feet to the fire in the case of ideological deviations such as appointing a transition director who hinted that having tens of millions of Americans without health insurance might be a bad thing. Conservatives mounted zero pushback whatsoever, suggesting that their newfound attachment to contractionary fiscal policy is a pure shift of expediency, to be discarded immediately if their party wins power and suddenly has an incentive to speed up rather than slow down the economy.

So Republicans in Congress are blocking Obama’s jobs plan, in the correct understanding that this will redound to their party’s advantage. When Obama attempts to explain this state of affairs, Romney can accuse him of making “excuses.” Obama can hammer home the point that Republicans are blocking his plan, but doing so has the side effect of making him appear partisan and ineffective.

Obama was arguing, correctly, that Republicans are the ones satisfied with slow private sector growth, and he is the one trying to boost it through economic stimulus. But his argument is complicated, and theirs is very simple.