This last weekend, Paul Ryan repeatedly dodged questions about the mathematical impossibility of the tax plan he and Mitt Romney are running on, and then, having burned through seven repeated questions and two minutes of dodging, insisted he couldn’t answer because the math would take too long. Today Bloomberg News spoke to Ryan and promised he could have all the time he wanted to get into the math. Guess what? He still didn’t.

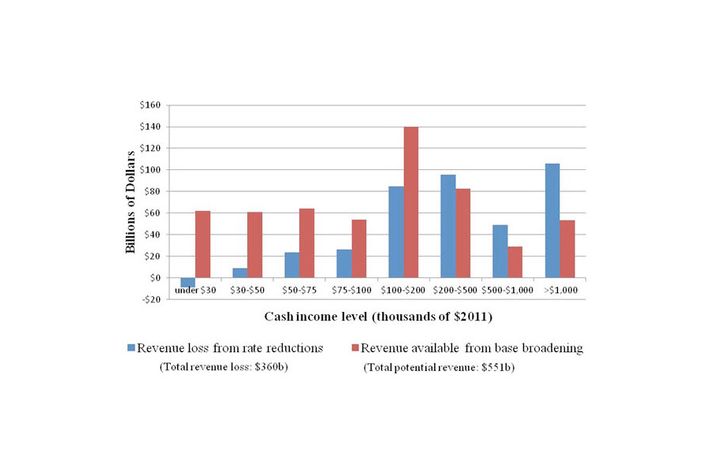

Rather than try to reconcile his irreconcilable promises, Ryan dissembled his way through another interview. To briefly review, the Tax Policy Center showed that people earning more than $250,000 a year would have to get a big tax cut from the Romney plan. The revenue lost from the income tax rate cuts they propose exceeds the available revenue from reducing deductions:

Ryan insisted the study has been discredited, which it hasn’t. The only reason he cited as to why it’s discredited is that “It doesn’t even assume economic growth.” This is a classic gripe of Ryan’s supply-side wing against mainstream economic analysis. It fails to assume that cutting tax rates will spark waves of economic growth, as conservatives are certain it will. But in fact, the study, in one of the many ways it bent over backwards to make the most favorable assumptions for Romney, assumed it would create faster economic growth. It adopted the model proposed by a name Romney and Ryan may recognize. Let me quote the study:

Nevertheless, even if one were to use the model from Mankiw and Weinzierl (2006) and assume that after five years 15 percent of the $360 billion tax cut is paid for through higher economic growth, the available tax expenditures would still need to be cut by 56 percent; on net lower- and middle-income taxpayers would still need to pay higher taxes.

“Mankiw” is Greg Mankiw, former Bush administration economist and current advisor to Mitt Romney.

Ryan likewise insisted that he would not spell out which deductions he would close, because this would make it impossible to negotiate:

You don’t say to Congress, to Democrats that you want to work with, “Take it or leave it, it’s everything, it’s all my way or the highway.” You say, “Here’s my framework. Obviously, the numbers add up. We’ve shown that. …

the best way to maximize success is to leave room for negotiation on how to accomplish the goal and, more importantly, we don’t want to cut some backroom deal like they did on Obamacare. We want to have, you know, Congress and the public participate in this debate about how best to do this.

But you haven’t shown it! Incredibly, Ryan is arguing here that public participation requires him to withhold his plans, rather than letting the public evaluate them during the campaign. Detailing your plans during the campaign would amount to a “backroom deal.”

Every time Ryan was asked about how he could make the impossible numbers add up, he retreated to abstract defenses of tax reform. For instance:

That’s - so look at the way our tax system works right now. We have a very narrow tax base. We raise about $1.2 trillion a year through income tax revenues. We forgo about $1 trillion a year through tax expenditures. So look how narrow that tax base is. So what we’re saying is, you can lower tax rates by 20 percent across the board, limit some tax expenditures and loopholes and deductions without hitting middle class taxpayers. …

Right, but nobody is denying that some form of tax reform is possible. What they’re claiming — indeed, what they’ve proven — is that Romney’s specific proposed form of tax reform is not possible. If he wants to keep current revenue levels, cut tax rates by 20 percent, and hold tax rates on capital constant, and he does, he will reduce revenue, increase effective tax rates on the middle class, or both. All Ryan can do is flee from the math.