I don’t think the deficit scold community is wrong about its general belief that the long-term deficit is too high. They’re obviously way too hysterical about both the scale and the immediacy of the crisis, but that is true of pretty much every interest group that wants to shake the world by its lapels and bring attention to their cause. The deficit scolds just happen to be particularly good at commanding elite attention for the pet cause.

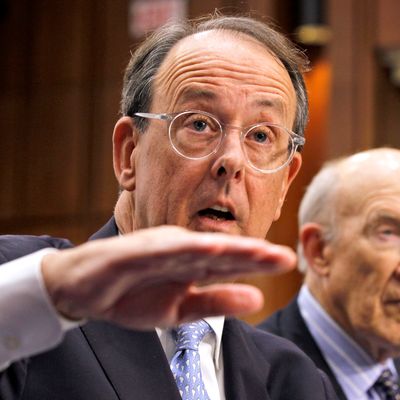

No, the main problem with the deficit scolds is not so much their policy beliefs as their political analysis, which holds, as a kind of philosophical first principle, that the fault for failing to reduce the deficit is everywhere and always shared in equal measure between the two sides. Here is Erskine Bowles today offering his sage analysis of the faltering debt negotiations between President Obama and John Boehner:

“When you think that for better or worse, America will spend over $40 trillion in the next 10 years and these guys can’t find $200 billion to close their divide and prevent an economic collapse, it is pitiful,” Mr. Bowles said in an email to the Wall Street Journal.

Now, first of all, note what has happened here. At the start of the negotiations, Obama asked to increase tax revenue by $1.6 trillion over current policy (which was a trillion dollars less than the Bowles-Simpson plan suggested), while Boehner countered with $800 billion. Everybody said they would wind up compromising at $1.2 trillion, because obviously the fair answer is always exactly halfway between the two sides’ positions. Obama has since progressively moved such that he is now occupying that blessed dead-center space with his $1.2 trillion revenue offer. So of course Bowles now thinks the problem is that both sides can’t agree.

It is true that the stated offers from Obama and Boehner are close enough that a failure to go the last inch is mystifying. But what’s the likely explanation here? Is it that Obama got really close to Boehner’s offer, pointedly said that he has not made his final offer and room remains to negotiate, but Boehner just mysteriously decided to drop out of the negotiations and hold a message vote? Or is it that Boehner figured out that he doesn’t have the votes even for his latest offer?

The answer, of course, is the latter. Not only is that a far more logical interpretation of Boehner’s behavior, it’s also the exact same thing that happened in 2011, when Boehner got swept up in the negotiations, cut a deal with Obama, and then surveyed his caucus and discovered it wouldn’t pass the House and he’d probably be deposed.

But even if Bowles knows this, he won’t say it, because it’s not a bipartisan kind of thing to say. The role of the deficit scold is to lay blame equally on the side that’s trying to do what you want and the side that isn’t. The pathetic thing about Obama’s behavior is his persistent efforts to shame the deficit scolds into abandoning their neutrality and convince them he is on their side and the Republicans aren’t. He is, of course. But not noticing this fact is a major part of the deficit scolds’ job description.