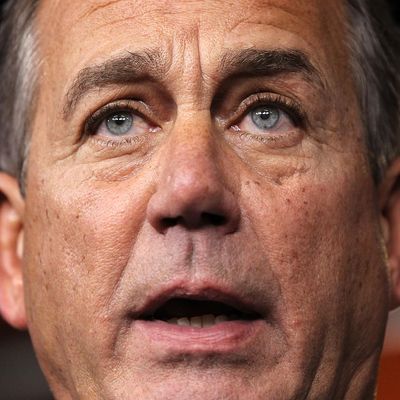

This week, John Boehner developed a new rule: Tax hikes would be permitted in any budget deal, but they must not exceed the total of new spending cuts. Not no new taxes, but one-to-one. It’s a new rule! White House officials seemed to be busily working to follow Boehner’s rule when he pulled out of the regular negotiations and instead focused on his strange Plan B vote.

The habit of formulating arbitrary rules, and subsequently discarding them, is becoming a key feature of the Boehner speakership. Boehner’s speakership is a years-long game of Calvinball.

The first major Boehner Rule — really, more of a guideline — was that he would try to pass bills with at least 218 Republican votes. Democrats could vote yes, of course, but Boehner’s goal was to assemble voting coalitions that did not need the opposing party at all. He was forced to abandon this repeatedly.

The second, and most famous, of the Boehner rules came about during the struggle over raising the debt ceiling last year. Boehner decreed that he would raise the debt ceiling only in return for securing spending cuts at least equal in size to the amount of the debt-ceiling increase. Of course, this rule, too, is insane. Over time it would force gargantuan cuts to government spending — far larger than Republicans themselves propose. (Even if Obama decided to sign into law the Paul Ryan plan, he would then have to agree to an additional $5 trillion in spending cuts in order to comply with the Boehner Rule.)

Likewise, Boehner’s latest rule makes no real sense. Boehner says the ratio of spending cuts to tax hikes has to be at least one-to-one. But last year, Obama and Boehner agreed to enact $1.5 trillion in spending cuts and to postpone until after the election how to handle entitlement spending and taxes. If those cuts had not occurred, and were instead being enacted now, then Obama’s latest offer would be well over one-to-one. Boehner just wants to exclude it. He also wants to exclude savings from reduced interest payments, which he and other Republicans have always counted before.

All of these rules serve a similar purpose. They attempt to channel the amorphous right-wing rage that propelled Republicans into the House majority into some sort of definable metric. The first Republican revolution from the nineties flamed out in a series of coups, and the threat of a recurrence has hung over Boehner since the beginning of his tenure. Boehner’s rules all bind him to the will of the conservative base, essentially allowing him to prove that he has fulfilled his duty to them and that any (inevitable) compromise is not the result of a sellout.

The 218 Republican votes guideline did that by essentially forcing Boehner to attempt to gain near-unanimity among his caucus. The debt-ceiling rule ran along the same lines. Republicans had won the House, were frothing mad, determined to use their debt-ceiling power to force concessions, but they couldn’t agree on what concessions were either realistic or sufficient or even whether raising the debt ceiling at all under any conditions was acceptable. Boehner’s debt-limit rule let him promise that the concessions he won would merely represent an endless string of concessions into eternity. (It’s possible somebody has done the math and explained how this rule couldn’t possibly be sustained, because Boehner is invoking this rule far less often these days.)

The spending-tax ratio rule is another way for Boehner to set up a marker that would constitute victory. What makes it odd is that he is defining this rule in a way that makes it very hard to fulfill. If he decided to count interest savings as spending cuts, as he has before, Obama could probably meet his terms.

But the amazing thing is that the administration actually seems to be taking the latest Boehner rule seriously, complaining that he is not interpreting it fairly enough but also hoping that the rule will pave the way for fair deals in the future. They actually seem to think that Boehner feels compelled to follow his own rules.