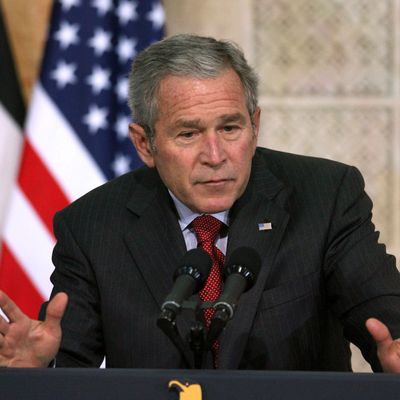

Immigration reform is pitting Republicans against each other, much as it did when George W. Bush attempted the same goal, only to abandon the effort in the face of a right-wing backlash. Though the relative strength of the two sides has tilted toward the pro-reform direction since then, the basic contours of the debate have not. Another thing that has carried over from that bitter schism is that the Bush administration itself — its legacy and place within the conservative movement — again lies at the heart of the dispute.

The conservative movement has always framed its case for dominance within the Republican Party in largely practical, not just ideological, terms. Phyllis Schlafly’s seminal 1964 book, A Choice Not an Echo, argued that moving right would not prevent Republicans from winning but enable it, by pulling to their side the majority of conservative voters who had been confused or discouraged by the lack of clear ideological differentiation between the parties. It did not work out terribly well for them in 1964, but Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election, and every subsequent Republican victory, has vindicated this strategy in the conservative mind. Republicans win when they hold fast to their principles, and lose when they wobble.

The trick to making the rule work lay in selective definitions. Reagan actually betrayed the movement time and again — on taxes, immigration, arms control, judges — but left office popular and was thus deemed a true conservative. Bush’s immigration reform gambit came at a time, 2006 to 2007, when the conservative movement was rapidly transitioning its approach toward Bush from a posture of hero worship to angry denunciations of a heretic who had never shared their views to begin with. The revolt against Bush became ensconced as party dogma: He was too “compassionate,” too Establishment, too big government, to faithfully carry the conservative banner.

The conservative revolt against Bush has always been the subtext of the party’s intramural war over immigration. From time to time, it has become the text.

A few days ago, Schlafly, still kicking around at 88 years old, denounced immigration reform as a doomed ploy. With familiar logic, she argued that Republicans should instead mobilize more white voters by nominating red-blooded conservatives (“I think when you have an establishment-run nomination system, they give us a series of losers.”). Schlafly did not mention Bush by name, but the implication was clear enough to summon Bush administration veteran Peter Wehner, who replied, “Phyllis Schlafly has lost the ambition to convince, which is just one reason why her counsel should be ignored.”

This outraged conservative talk-show host Laura Ingraham (“How dare ex-Bushies,” she wrote, ” — the same crowd who practically destroyed the GOP only a few years ago — make political criticism of someone who defeated the ERA, and who played a major role in building Reagan’s original coalition?”) Wehner, without directly referencing Ingraham, then defended the concept that a true conservative can engage in political compromise — conservative, he argued, required “wisdom and good judgment, sobriety, foresight and prudence.”

Ingraham then launched an epic denunciation of Bush, notable for its comprehensive sweep:

Looking back, was it “wisdom and good judgment” to launch two wars with no coherent plans for victory or payment?

Was it “sobriety” to allow millions of illegal immigrants into the country?

Was it “foresight” to ignore signs that a housing bubble was in the offing, or to run up huge deficits all through the Bush years?

Was it “prudence” to put people like Alberto Gonzalez and Mike Brown into positions of authority?

Is it “wisdom and good judgment” to let Barack Obama and Chuck Schumer re-write the nation’s immigration laws in a manner that favors the left?

Wehner then mounted his latest passionate defense of the success and conservative purity of the Bush administration (“where Ingraham’s arguments become most confused is in her angry attacks against George W. Bush, anyone who worked for President Bush, and the entire Bush family.”).

For the record, I fall in the middle of this dispute. Wehner is right that Bush’s administration was mostly conservative; Ingraham is right that it was mostly terrible. On Ingraham’s side of the argument, Bush committed historic foreign policy blunders, presided over widespread incompetence, turned a budget running a couple-hundred-billion-dollar surplus at its peak to one running a couple-hundred-billion-dollar deficit at its peak, and managed to combine a weak recovery, massive bubble, and once-in-a-lifetime recession.

Where Wehner draws blood is where he notes that Ingraham supported nearly all of the Bush policies she now denounces. Indeed, in his capacity as caretaker of what was then a flourishing Bush cult of personality among the conservative movement, Wehner saw firsthand just how worshipfully Ingraham regarded the 43rd president at the time. “Ms. Ingraham showed an almost supernatural ability to contain her disdain for President Bush when she was invited to meet with him in the White House,” he writes. “Who knew that underneath her good manners and supportive words lay a seething volcano?”

Ingraham, notes Wehner, is oddly fixated upon Bush’s appointment of Harriet Miers, an indefensible decision, but one that Bush did correct by forcing her to withdraw. The reason Ingraham likes to cite Miers is that it is one of the few Bush failures that took place after conservatives began to cast him as a heretic. The rest of the litany — the foreign policy blunders, the deficit-financed tax cuts, the deficit-financed Medicare benefit — occurred when Bush still enjoyed the passionate support of Ingraham and her fellow conservative movementarians.

Ingraham assumes that Bush’s failures must go hand-in-hand with his ideological deviations, essentially defining his failures by their results (deficits, a huge bubble) rather than by their policies, which did indeed reflect exactly what conservatives demanded at the time. The ritual conservative denunciations of Bush are intended to cleanse the ideology of Bush’s sins, and through sheer repetition, most of the conservatives have made the world forget just how fervently they supported Bush through most of what they now call his errors.

The tension that lay beneath this delicate balance did not rise to the surface because conservatives have been mostly united throughout the Obama era. Establishmentarian Republicans and grassroots activists alike endorsed the party’s posture of total opposition to the entire Obama agenda. Immigration reform is the first time a serious tactical split has arisen within the party — the first time when a significant GOP faction has decided the party’s interests dictated cooperating with Obama in some form rather than opposing anything he could support. And so the denunciation of Bush is now being used not merely as a ritual incantation but as a conservative weapon to discredit fellow Republicans.

That explains the unusual bitterness of the internecine feud between former friends. It also explains why Republicans needed Marco Rubio, not Jeb Bush, to lead the immigration reform push. But it also points to a larger question facing the party. Conservatives need to decide if their denunciations of Bush are a mere rhetorical device or a genuine strategy.