Valance Cole has at least two key facts on his side in his long struggle to overturn a manslaughter conviction for a 1985 Brooklyn killing that has kept him in prison for more than a quarter century. The first is that the homicide detective who built the case against him is closely connected to an evidence-faking scandal that has prosecutors — and now a New York State Supreme Court judge — reexamining dozens of old convictions. The second is that another man has been trying for years to confess to the killing in question.

Denzil Smith, 54, is the first to admit that he shot Michael Jennings on Aug. 4, 1985. He has confessed in detail no less than four times since 2007, most recently on video. Smith says he spoke up because he thinks it’s unfair that Cole has spent all this time in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

The killing went down, Smith says, after he discovered someone had swiped his cocaine stash. He blamed a guy named Trini and went looking for him on Fulton Street in Brooklyn’s rough — in those days, anyway — Bed Stuy neighborhood. Soon enough, he found him.

“So I’m talking to him, ‘Listen big man, if you don’t give me what I want, I’ma hurt you,’” Smith told an investigator in a video-recorded interview last March. “And then I’m talking to him — now here comes another guy.” The other guy was Jennings, a friend of Trini’s. Before long Smith and Jennings were getting into it. Smith recalls Jennings reaching for something silver and shiny in his waistband.

“What am I supposed to do?” Smith asked the video camera. “He’s the one who initiated it.” Smith drew a .38 revolver and shot Jennings twice. But the shiny object was just a Walkman. Smith tossed his gun under a car and fled. Jennings died that day.

Smith tells the story from his native Guyana, beyond the easy reach of American law enforcement. He was deported from the United States a decade ago after threatening to kill a girlfriend and refuses to return to New York. But for years he’s been trying to get Cole released, and for years the Brooklyn district attorney’s office has dismissed his confessions as irrelevant. “I was just helping an innocent man in jail,” Smith told the investigator. “Because I know he was.”

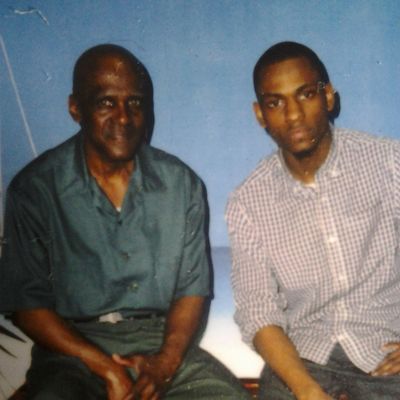

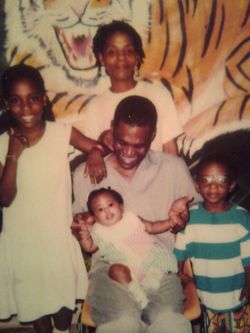

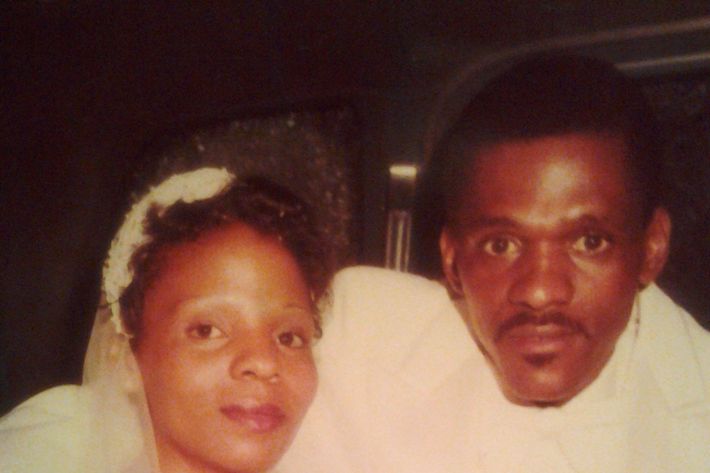

Cole, a social club owner who had had run-ins with the police over drugs and an earlier shooting, was arrested seven months after Jennings’ killing. Based mainly on the testimony of two witnesses — one a drug user who later recanted saying he’d been coerced, the other a man whose version of events stood in stark contrast to that of other witnesses — Cole was convicted of first-degree manslaughter in 1987 and received a 25-year sentence. When his prison term ended this year, he was handed over to federal custody, where he awaits deportation, also to Guyana. He has been fighting the conviction all along and says his main motivation now is to spend time with his grandchildren. “I missed that chance of being a part of my children’s lives,” Cole, the father of six, says. “I want to be part of my grandchildren’s lives.”

An unfolding scandal around retired Brooklyn homicide detective Louis Scarcella has given Cole and his legal team new hope. Scarcella landed on the front page of the New York Times in May and dozens of his cases dating back to the eighties and nineties have come under review by the Brooklyn district attorney’s office and a state Supreme Court justice. Already, David Ranta, the man whom Scarcella helped to convict in the 1991 killing of a prominent rabbi, has been freed. A witness in the 1995 shooting of a little girl claimed to have been coached, prompting the New York State Board of Parole to release the man convicted of her killing. In its reporting, the Times noted that Scarcella had relied very heavily, across many cases, on the testimony of a well-known crack addict named Teresa Gomez. To say the least, she claimed to have seen a remarkable number of murders.

The lead detective in the killing of Michael Jennings — the man who built the case against Cole — was Louis Scarcella’s longtime partner, Stephen Chmil. While Chmil has not been the primary focus of the inquiry, some of the convictions under review by the District Attorney’s Office are cases that he shared with Scarcella — as the two jointly worked the Ranta case. But the Cole case has not been reopened, despite sharing some notable characteristics with convictions now under review, including a drug-addicted key witness, claims of coerced testimony, and charges that detectives ignored evidence that pointed to another killer. (Scarcella was not involved in the Cole case.)

“Valance is most certainly innocent,” said Rebecca Freedman, the assistant director of the Exoneration Initiative, a nonprofit organization that works to clear innocent people without DNA evidence, and which has taken up Cole’s case. “The police files suggest that Detective Chmil and his partners engaged in questionable practices when it came to certain witnesses, putting pressure on them to either implicate Cole or to prevent them from exonerating him. And it’s a great injustice.”

Even Chmil acknowledges that Jeffrey Campbell, one of the main witnesses against Cole, was a crack addict. Campbell implicated Cole after being arrested for robbery. Years later, dying from AIDS, Campbell recanted and said Chmil had promised the robbery charges would be dropped if he testified against Cole.

Speaking to Daily Intelligencer, Chmil conceded the similarity between Campbell and Theresa Gomez, the crack-addicted serial witness that his partner relied upon so heavily.

“Campbell was a lot like her,” Chmil said. “He was a street guy. I know I dealt with him a few times. Sometimes he’d tell you the truth, sometimes he wouldn’t.”

Still, Chmil said he did nothing wrong in the Jennings case. “We put away enough bad people,” he said. “To frame somebody … ” He paused. “I’m Christian. I couldn’t do that in my heart.”

But defense lawyer who went up against Scarcella and Chmil in the eighties remembered Campbell saying police threatened him if he didn’t testify.

“Campbell was probably the most unreliable witness you could ever want because he was such a bad drug addict. He was such a bad crackhead, and certainly easily manipulated,” Michael Baum said. “These guys were pros at using these junkies and druggies and prostitutes to come in and testify.”

The other main witness against Cole, Charles Ford, did not identify him from a lineup until six months after the shooting. And Ford’s account of what happened that day – that the shooter was a disgruntled customer angry about inferior drugs he had bought – was at odds with everyone else’s from the scene.

By contrast, Cole’s legal team points to Smith’s four separate confessions, five witnesses who identified Smith as the shooter, and multiple other witnesses who provided a description of the shooter that matched Smith. (The two men were far from lookalikes: Smith stands five foot eight, while Cole is over six feet; at the time of the shooting, Smith was 25 years old, Cole 39.)

Cole has challenged his verdict at least ten times, always unsuccessfully. “Non-DNA work is really difficult and courts are reluctant to grant relief even in the face of very powerful evidence of innocence,” said the Exoneration Initiative’s director, Glenn Garber.

Now, in what could be Cole’s last chance to clear his name, the Exoneration Initiative is again trying to overturn his conviction. At the center of a new legal motion filed in July in New York State Supreme Court is Smith’s videotaped confession.

“This is his last shot at justice,” Freedman said. “It deserves a real searching inquiry into the truth of what happened with this murder and who did it. And even if he is deported that doesn’t change the fact that there was a wrong done to him and it needs to be righted – not just for him but for the entire system.”

Though Cole and Smith were both from Guyana and had met, they say they were not friends. Cole owned the social club in Brooklyn, but lived with his family in an apartment in Queens, and on the afternoon of the shooting, says he was at home waiting for relatives to arrive. His nephew had just died, and the funeral had been the day before.

Cole, who also has a conviction for heroin possession, wonders if he was targeted because in street slang, he had “beat a body”: He was found guilty of manslaughter after killing a man at a store he owned on Marcy Avenue – he says the gun went off during a robbery, prosecutors accused him of selling marijuana from the store – but he never went to prison. The reason he didn’t is that the judge in the case disagreed with the jury’s decision, stating at sentencing: “it’s a repugnant verdict, it’s a little inconsistent with the facts in the case. In this case, I do not feel it’s necessary to give you jail time.”

The Brooklyn district attorney’s office declined to comment. But in legal papers, it called Smith’s confession yet another unreliable account of Jennings’ killing, calling it inadmissible hearsay. It focused on one unclear reference to the time of the murder to discount the entire statement.

Cole’s 29-year-old son Marlon said his father has never seemed bitter or angry. But life became difficult for the family after Cole was sent to prison. “When he went everything changed,” Marlon Cole said. “It was hard. My mother became an instant single mother.”

Cole recalled one prison visit when his wife did not have the 35 cents to allow Marlon, then about 5 years old, to buy a bag of chips. “She said all the money I have in my possession is for us to catch the train to get back home,” he said. “I went back to my cell and I cried about it, knowing I’m innocent and my family had to suffer.”

When asked about whether Cole should be exonerated, Chmil said: “You can quote me: If things work out for him, fine. But I stand by cases I worked on.”