For a dozen years, World Trade Center watchers have grown accustomed to a steady drip of disappointments. The list of delays, petty grievances, bastardized designs, exploding budgets, and truncated ambitions is too lengthy to rehash. Finally, though, as buildings have started to rear up, shining, from the mire, the surprise is how much optimism the whole project can still produce. I have watched the soft messy tangle of history and ganglions of infrastructure covered over by a great concrete quilt and thin sheets of glass. The horrific pit we will never forget has been filled in, built up, and dressed in a palette of steel and pewter and charcoal and slate, a whole range of dressy blacks and grays accented by reflective surfaces.

Walking through this vast campus now, you might be fooled into thinking of it as a monument to rational modernity. The symmetrical, super-tall tower rocketing skyward, the artful arrangement of prisms at its much smaller but still colossal neighbor, the memorial’s rectilinear voids—the whole complex exudes geometric cool. But the World Trade Center isn’t just an achievement of government-subsidized capitalism or sophisticated engineering. It’s a collection of enshrined emotions. Fear and defiance gave us the bulked-up Tower One, whose height of 1,776 feet, back when it was called the Freedom Tower, was determined not by any market or structural considerations but by pure historical symbolism. Grief produced the memorial plaza. The transportation hub embodies the need for uplift that a decade ago even cold-eyed pragmatists felt.

It’s been astonishing to watch those feelings harden into form. I visited One World Trade Center two winters ago and rode a hoist up the side to the 90th floor, still a nest of columns and beams. Someone had torn a hole in the mesh that wrapped the exposed floors (and still encloses the top, as seen here), framing an unfiltered view. At the center of the structure, where two immense cranes raced each other to the sky, a battalion of lathers, ironworkers, and welders lit the scene with blowtorch sparks and started up a hollering chorus. One man gripped a thick steel rod that another banged with a sledgehammer. It looked like a medieval engraving showing us labor—“The Blacksmythe’s Forge”—a reminder that this sleek technological marvel was built by hand.

Below, hundreds of workers in variously colored vests and hard hats clambered over the many structures and pits and naked steel cages. I had the sense of an unfathomably complex undertaking, carried out on an imperial scale. The buildings on the site rise above a pick-up-sticks pile of conduits, subway tubes, train tracks, truck ramps, and interlaced foundations. Every change of plan triggers a whole cascade of others.

A year later, Tower One had evolved into an immense festive skeleton arrayed in multicolored lights like some kind of mutant lawn ornament. On stormy days, the wind roared through the open floors, producing an unearthly shriek that could be heard for blocks. The building was still raw, hopeful, and wild.

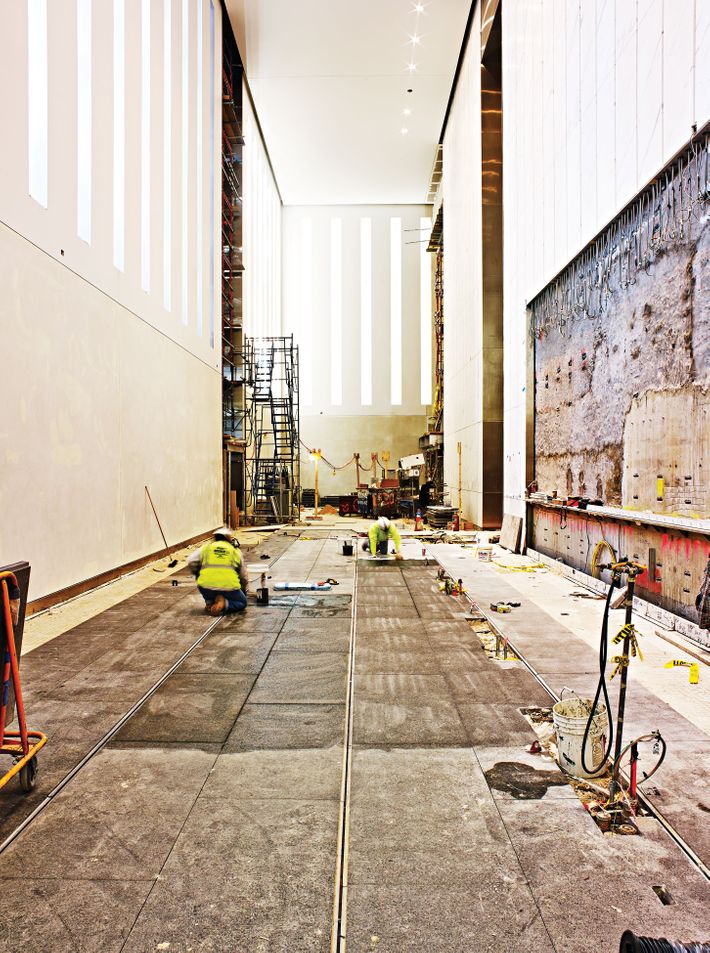

Now it’s been uneasily domesticated. The lobby is a white cell, with high windows piping in vertical strips of daylight from above. Warp-speed elevators stand ready to beam workers up to their cubicles. Construction continues, but already the marketing team has kitted out the 63rd floor with sample offices and videoconferencing rooms. The curtain wall’s thirteen-foot panes of glass make the interiors vertiginously airy and give the exterior an almost liquid seamlessness, as if the façades were coated in shellac.

The almost-finished, nearly $4 billion skyscraper, designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, tries to maintain an equilibrium between ferocity and elegance, brawn and poise. Like the original Twin Towers, the structure is a rectangular block—only here each corner has been shaved away so that the building tapers from square base to smaller square top, passing through a series of octagonal floors. The same thing happens in reverse at the base, with the structure fattening instead of narrowing as it rises 200 feet. That was one frill too many for the Durst Organization, which is co-developing the building with the Port Authority, so the company hid it behind an ordinary cube of cladding.

There’s a lot of such mild deceit in this building. When Condé Nast moves in about eighteen months from now, employees can approach along a newly extended Fulton Street and through a handsome glass curtain wall, as if this were just any corporate headquarters. But the lobby doesn’t open directly onto the street; it takes cover behind a blast barrier and backs onto an elevator core built as solidly as the Hoover Dam, with sides of ultradense concrete six feet thick. The message is clear: no soft targets here; anyone with malicious intentions should just keep moving right along.

The tower is unpeopled at the bottom and the top. The base is a massive concrete bunker, impervious to all the threats that the NYPD could think of. Something there is that doesn’t love a blast wall, so SOM has tricked out the first twenty floors with the architectural equivalent of Swarovski crystals: pairs of glass fins, cocked at different angles and illuminated from behind so that the façade will glitter 24 hours a day.

There’s more razzle-dazzle up top. The building proper rises just to the height of the original World Trade Center (a mere 1,368 feet), but it’s capped by a 408-foot spire whose principal purpose is to win the title of tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. What a strange griffin of a building, with its armored base, its lean glass torso, and its elaborate ceremonial headgear. The divisions reflect a culture struggling to integrate transparency and security. The NSA’s headquarters is a glass building too.

The theater of construction still plays out in Santiago Calatrava’s transportation hub. On a bright, frigid day, I step into the oval “oculus,” and it’s like standing in the center of some ruined arena or prehistoric observatory. Immense pieces of molded steel sit on plinths, like the bones of some giant fossilized beast. Above, curving steel fingers reach for each other. The space between them frames a worm’s-eye view of the surrounding skyscrapers, which seem to converge toward a point in the sky. Calatrava’s aesthetic emerged from the ruins of the ancient world—all those bleached, perfectly proportioned skeletons gleaming in the sun. That kinship is most obvious now, before the openings are glassed in, the two sides of the roof finally meet, and the whole structure acquires its final pristine gloss—before, in other words, the structure gets un-ruined.

You can get a taste of the final result in the block-long pedestrian concourse beneath West Street, which leads from the temporary PATH station to the World Financial Center. It’s surely the most luxurious tunnel in New York, paved in white marble and vaulted with white steel ribs that swoop up from the floor and make a boomerang turn along the ceiling.

Calatrava is suddenly, stunningly out of fashion, amid reports of his leaky roofs and wobbly bridges, budgets gone kablooey, and European government ministers embarrassed to have authorized such bankrupting extravagance. He has turned from a humanist hero into the preeminent architect of self-indulgence, who thrived in the overheated prerecession atmosphere but is now out of step with our supposedly chastened tastes. It doesn’t help that construction delays caused the transportation hub’s cost to pole-vault from $2 billion to nearly double that, making it the world’s most expensive station even though it’s far from the busiest in New York. The word obscene has been tossed around.

The irony is that when he first proposed his design, it was virtually the only component in the complex that met with instant hosannas, and it remains one of the only elements that did not have to be radically reconceived along the way. In 2004, politicians, journalists, civic advocates, and construction professionals gathered in the World Financial Center to watch Calatrava sketch a bird on a sheet of white paper and then, with a few more lines, turn that bird into a train station. Here was a rare gush of pristine vision, infrastructure—that diseased-sounding word—transfigured into architecture. It’s difficult to remember at this remove how many of us desperately wanted the process to be ennobled, to be something other than a plain old New York–style real-estate deal.

Later those witnesses felt a little foolish, as if the architect were performing a conjuring trick and picking everyone’s pockets at the same time. But he wasn’t. He had an idea, and everyone loved it. It’s still a good idea, even if its admirers have soured on it. As the cost rose, the design thickened—more steel, less glass—and those silly movable wings were mercifully pinioned. But the station that’s under construction now remains a thing of awe and wonder. The domed chamber will eventually become the vast indoor plaza it was always intended to be, the lofty, spacious core of a clotted part of town.

Nowhere is the tension between optimistic gleam and gnarled history more stark than in 4 World Trade Center, the freshly completed tower by Maki and Associates. It’s the epitome of the office building as gadget. The out-of-the-box sheen, corners sharp enough to shave with, surfaces so smooth and pristine that a fingerprint reads like graffiti, lines you could sight a laser by—every detail and finish is calculated to stimulate pride (if you belong there) or envy (if you don’t). The elevator hall’s marble isn’t just white; it’s frothy and unblemished, as if Maki had skimmed off the cream of the quarry and discarded everything else.

To what end, this fetishized perfection? (The only confirmed tenants so far—the Port Authority and the city’s human-resources department—could probably manage with less luxe.) Maybe it’s that the building performs the same consoling magic on the site’s violent history as hospital corners and gleaming uniforms do: It neutralizes gruesome memory, substituting violence with order. The upper floors provide spectacular crow’s nests from which to scan all the soaring urbanity that stretches from the Poconos to the Long Island Sound. But to gaze on the memorial, you have to press yourself against the glass and look past your feet. Or you could step across the granite-paved lobby, slip through the glass membrane, and emerge onto a block of Greenwich Street that the old World Trade Center had obliterated and that has now been restored. Cross that, and you come to the memorial plaza and the pair of dark-polished wells of melancholy.

It’s okay that all this impeccably tailored corporate design glosses over the past and hides the saga of destruction, dismantlement, and rebuilding. The site is becoming so blessedly normal! A chorus of planners always promised that this wounded place would one day be sutured back to the rest of the city and that the passage from profane streetscape to contemplative sanctum would be smooth and clear. It hasn’t happened yet, since fences still haven’t come down and visiting the memorial plaza still requires a pass. But soon crowds will flow freely into this traumatized site, smudging its borders, so that another decade from now we’ll hardly see the scar.