Wearable computing — the category of gadgets that includes Google Glass, fitness devices like the Fitbit and Jawbone Up, and a growing number of smart watches — has never been my favorite tech genre to cover. It’s one of those better-in-theory ideas that often sprouts from Silicon Valley’s imagination, and despite a decade’s worth of hosannas like the Wired cover story that proclaimed that “wearable tech will be as big as the smartphone,” no truly impressive wearables ever seemed to materialize. A Samsung watch? Pass. A bracelet that vibrates when I’m getting a call? Kind of cool, but hardly revolutionary.

So, naturally, as wearable computing has been developed for dogs (believe it or not, there are two such gadgets: Whistle and FitBark) and newborn babies (Sproutling makes a wearable baby monitor, and Intel is making a “smart onesie” for infants), my eye-rolls grew by an order of magnitude. Why does a dog need to be Bluetooth-connected? And what kind of psychopathic helicopter parent needs minute-by-minute updates on their baby’s vital signs?

But recently, I tested Whistle, one of the Fitbits for dogs, and some of my confusion faded. Now, I think I was probably being too harsh about the future of wearable computers. Unlike Daniel Gross, I don’t think the entire genre is a total fad, destined to be used by a niche market and forgotten by everyone else. I just think certain types of wearables stand a far better chance of succeeding than others.

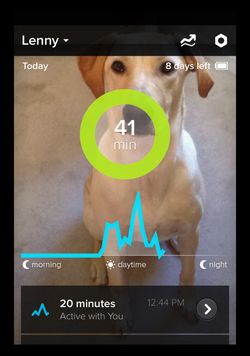

The premise of Whistle is simple: It’s a little circular sensor, about the size of a half-dollar coin, that attaches to your dog’s collar. After it’s on, your dog’s activity level is tracked by a three-axis accelerometer, just like your steps would be counted by a Fitbit or Jawbone band. The device syncs wirelessly and displays activity levels in chart form on a mobile app. Here’s what the home screen for Lenny, my dog, looked like:

So far, not life-changing. Whistle became slightly more valuable when I took off for vacation and left Lenny at a sitter’s house for a few weeks. The device allowed me to check on him from afar every day, making sure he was getting the exercise he needed. I could see when he went for walks, when he napped, and when he retired for the night. If he hadn’t spent enough time outside, I could have called the sitter and asked for an extra walk. (Not that I would have, but it was a theoretical possibility.)

As of today, Whistle is mostly a novelty item — at $129.95 per device, I can’t imagine it taking off except among the most neurotic dog owners. But you can see the conceptual appeal. If it cost $20 and needed to be recharged less frequently, I might buy one, if only for psychic reassurance that my dog is alive when I’m out of the house.

The biggest question that has to be asked of all new wearable devices hoping to reach a mass market is: Does this vastly simplify or speed up an existing process? For Whistle, the answer is no — most dog owners don’t currently keep tabs on their pooch’s minute-by-minute activity using pen and paper. Ditto baby monitors — having a baby’s vital signs “displayed on a coffee cup or a candle” 24/7 is likely to make parenting more complicated, not less.

But I don’t think that the entire category of wearables can be dismissed out of hand, simply because some examples seem less useful than others. Some wearable devices will actually allow a vast improvement in the tasks we already do every day. And once the initial obstacles — short battery life, ugly devices, high costs — are dealt with, the wearables that do streamline their wearers’ lives will overcome novelty status and become widespread very quickly.

Take Google Glass. Like most people, I’d hesitate to wear it in its current form. But I can also see how, as Mat Honan reported about his year wearing Glass, wearing a computer on your face allows you to “get in and get out” of digital interactions much more quickly than reaching for your phone 100 times a day. Used properly, computerized glasses can be an efficiency tool, not a distraction. And once the social stigma wears off, people will begin to see the time-saving benefits of ditching handheld phones for something that sits directly on your face.

I agree with Gross that “wearable technology is an add-on, an accessory, something that comes on top,” and that its adoption would require people to change their habits. But I don’t think this dooms the category. It just means that wearables, like every other consumer product on the market, will need to show that their benefits exceed their costs. The ones that succeed en masse will need to provide big improvements to everyday tasks, or be so cheap and intuitive that even minimal improvements justify the expense. A $130 activity monitor for dogs might not go completely mainstream, but other devices will. Let’s not write them all off just yet.