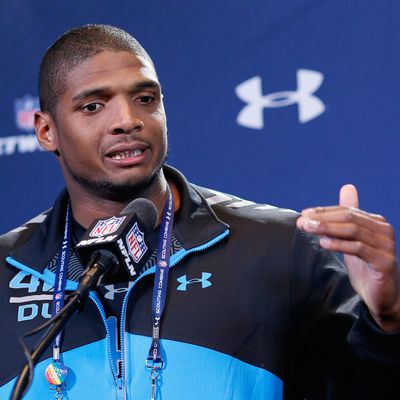

The NFL combine is essentially medical in spirit, less a football tryout than a biomechanical examination, and so there was a great deal of attention on the University of Missouri defensive end Michael Sam this morning when, after false-starting twice, he rumbled down a 40-yard stretch of Astroturf as fast as he could force his body to go. The sprint took him 4.91 seconds. “Disappointing, Mooch?” an NFL Network host asked the former Detroit Lions coach Steve Mariucci. “A bit,” Mariucci allowed. The consensus before the sprint had been that Sam, who came out as gay two weeks ago, looked like a mid-round pick — not a superstar, but a pro, with a real career ahead of him. Now that looks a little bit more like the optimistic scenario. Even if Sam were shaping up as an on-field superstar, he would have had a great deal arrayed against him: The league’s inherent risk-adversity and political conservatism, its reluctance to interfere with the often brutal and retrograde politics of the locker room, the essential disposability of nearly every player. As a slightly lesser figure in football terms, the sport’s first openly gay role player, those forces seem more daunting still.

And yet, over the past few days, with the league’s notables gathered in Indianapolis, a consensus has seemed to take shape, and it has been surprisingly, sometimes movingly, pro-Sam. This weekend, the NFL Network’s lead host Rich Eisen denounced the notion that Sam’s sexuality and the perceived media storm surrounding the player would operate as a “red flag” that would dissuade teams from drafting the defensive end. “Just the concept that he would be a red flag, its so ludicrous,” Eisen said. (The whole segment is worth watching.) “The media scrum that supposedly would be an issue for any NFL team — our colleagues in the media couldn’t even fill out a ten-minute session with questions [for Sam, during his mandatory combine press conference]. It’s asked and answered.”

The league’s general managers, a constitutionally taciturn bunch, echoed the sentiments. “I think our locker room has had the tendency to adjust to things a lot smoother than maybe the media does,” said Ozzie Newsome, general manager of the Baltimore Ravens. “I think it’s widely known that every locker room has a number of gay individuals,” the Atlanta Falcons’ general manager Thomas Dimitroff said. “I really believe the NFL is quite evolved.”

It is that last sentiment, Dimitroff’s, that feels the most telling. The NFL, bedeviled by the concussion epidemic, wants a chance to show it is more progressive than many think — wants to prove that it is, in Dimitroff’s phrase, “quite evolved.” And Sam himself has given the league its chance. The defensive end has managed his very public and fraught coming-out with tremendous dignity and frankness. But he also managed to convey to the league itself that he saw his own historic status as a source of pride but also something of a distraction, from the more important business of trying to shave a few hundredths of a second off of his 40-yard dash time. In so doing, Sam flattered the league’s image of itself: That the players just want to get on with things, it was the outsiders — the media — who kept making so much fuss. “I said I wanted to be seen just as a player, and that’s how all the other guys at the combine see me,” Sam told the analyst and former All-Pro Matt Millen today. “That’s what you are,” Millen told Sam.

But there was an awkwardness in that exchange, and a bigger ambiguity lurking behind it. Was all of this enthusiasm for Sam just public relations, or did the lumpen NFL — the players and scouts and assistant coaches — really believe the line? When they were speaking anonymously, NFL executives and personnel were considerably less sunny. “Not a smart move,” one assistant coach told Sports Illustrated’s Pete Thamel, predicting that coming out would cost Sam money. “I don’t think football is ready for that just yet,” a personnel assistant said. There were some dark murmurings from the locker room, too: “Imagine if he’s the guy next to me and, you know, I get dressed, naked, taking a shower, the whole nine, and it just so happens he looks at me,” the New Orleans Saints linebacker Jonathan Vilma hypothesized. “How am I supposed to respond?” (Vilma later walked those comments back somewhat.) How you think the NFL will cope with Michael Sam — whether he will be given a fair shot — turns in part on whether you believe the sunny public statements or the darker private ones.

My money is on the public statements. Part of this is no doubt thanks to the increasing presence of gay men and lesbians in American cultural life, partly owing to openly gay NBA player Jason Collins (who made his first appearance after coming out as a Brooklyn Net this weekend) and partly owing to the vociferous support for Sam from his college coaches and teammates, to whom he was out and whom he led. But there is something else, too. The NFL is by culture and by bylaws hierarchal, and the message from the league’s own commissioner, Roger Goodell, who happens to have a gay brother (“We truly believe in diversity and this is an opportunity to demonstrate it,” commissioner Goodell said), from its owners and general managers, from its own television network, has been discernibly pro-Sam. Decisions on whom to draft are made semi-publicly — more publicly, at any rate, than an anonymous conversation between a single scout and a reporter. Owners are in the room, or hovering nearby, as are team public relations personnel. In this environment, the talk about Sam’s “character” and his potential effect on a team is likely to mirror the declarations of senior league officials and may very well be more positive than negative. Which doesn’t mean that Sam will necessarily be drafted as a star; he may well have to fight his way onto a roster. But Sam’s enduring achievement lies in his forceful emphasis that all he wanted was to be seen as just another prospect, as a man struggling to push the limits of what he could do physically, to run a little bit faster, to lift a little bit more. The NFL is still surly, defensive, inward-gazing, resistant to change. But in Sam, increasingly, it is coming to see not an interloper but one of its own.