The Weather Channel’s headquarters are located in an anonymous office park on the north side of Atlanta. It’s a natural home—Atlanta has been a cable-company town since Ted Turner first beamed his Superstation from West Peachtree in 1976, and the city’s massive airport and (generally) mild weather make it a good base from which to scramble the network’s field reporters. The Weather Channel logo—that royal-blue square, virtually unchanged since the dawn of cable—hangs demurely from the top story, while a gaudier scrim adorns the lobby windows, loudly proclaiming the company’s new slogan: “It’s Amazing Out There,” a cheery take on the increasingly disturbing weather punishing our shores, and that cheeriness is about to be put to the test. It’s January 28, and a powerful snowstorm has descended on Dixie.

Downstairs in the lobby, nonessential personnel, clad in makeshift winter outfits—sweaters layered over sweaters, creaky parkas—are fleeing to their sedans to pick up the kids or the last loaf of seven-grain at the Publix. Except nonessential personnel in anonymous office parks across this city of 5 million have all just had that same idea, and the roads are already so congested that cars can’t even get out of the Weather Channel parking lot. One by one, staffers trudge back inside, resigned now to ride out the storm at their desks. It’s looking like dinner tonight will be a turkey wrap from the Doppler Deli. “It’s ugly out there,” says one employee, flashing his badge as he comes back in from the cold.

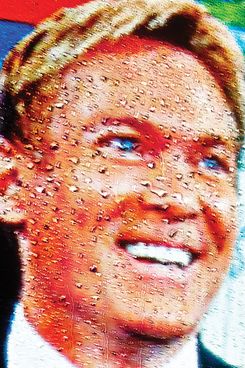

Upstairs, Sam Champion is watching from a fourth-floor window as the snow begins to accumulate, and he can scarcely contain his excitement. A Kentucky native, he spent more than two decades in New York, first at WABC and then on Good Morning America, and when the topic is weather, he talks at a New Yorker’s rapid clip. This, he says, is why he left ABC for the hinterlands of narrowcast cable, despite being part of the GMA team that finally overtook Today in the ratings after nearly two decades at No. 2. Though currently clad in black jeans and an oatmeal sweater, Champion will shortly don a charcoal suit and a candy-striped purple tie and co-anchor two hours of wall-to-wall storm coverage. And he won’t have to sacrifice a minute of barometric analysis to the State of the Union address, which President Obama will deliver later this evening.

“In network news, I come to them and say, ‘I’ve got a snowstorm in the South, and it affects millions of people, from Houston all the way to North Carolina, who don’t get snow, who don’t get ice, who don’t get freezing rain, and don’t know what to do—I need resources; I need live shots; I need time in the show.’ They’re saying, ‘Yeah, but the president’s talking.’ ”

With all due respect, Mr. President, Sam Champion thinks Mother Nature deserves top billing. “Because I think that this story is just as big to the people who face it as the State of the Union address is. Because it colors every moment of your life, and a bit more than whatever the announcement will be tonight in Washington. Because this affects you immediately. It impacts you directly.”

On March 17, Champion will launch a new morning show, AMHQ, which will aim to prepare viewers for their day out in the elements, pitting the dismal weather against his sunny personality and sky-blue eyes. “I don’t have to have an argument about where the weather goes in the show,” he says. “It is the show.” For now, however, there’s snow falling on the poorly prepared city of Atlanta, and Champion is eager to get behind an anchor’s desk.

“It’s a calling,” he says.

If ever the world needed a weather channel, now would seem to be the time. The weather hasn’t just been bad this winter—it’s been Book of Revelations bad. In 2014 alone, there’s been a crippling drought in Southern California and record snow accumulations in the Midwest. In early January, temperatures across the country dropped precipitously, and dangerously, thanks to the polar vortex, a weather phenomenon that sounds like a doomsday weapon. We’ve been obsessing over what’s coming next, devouring weather forecasts as if they were dispatches from the front of a losing war. Weather small talk, once a benign staple of the elevator, has turned more urgent and technical—we speak now of strategic salt reserves, of the Sperry-Piltz ice-accumulation index, of whether the “precip” estimate will “verify.”

In a not entirely dubious recent segment, a Weather Channel anchor interviewed a clinical psychologist, Josh Klapow, who explained that the weather has been so extreme that it’s left some Americans experiencing acute anxiety and even post-traumatic-stress disorder. People who have been cooped up for too long in a storm might be susceptible to a malady he calls “snow rage.” The symptoms? “People will throw things; they’ll break things; they’ll curse. They may go after a neighbor or a loved one.”

All of this has, of course, been helpful to the Weather Channel, which will post strong year-over-year ratings for January, despite being dropped this year by the satellite provider DirecTV in a contract dispute. No other news organization has the Weather Channel’s ability to cover the nasty stuff. Early in its history, the network realized that in severe weather, we don’t just want a forecast—we want to see the weather. We want a fellow human being to stand in front of a camera, his face partially obscured by his windblown parka hood, and tell us what it’s like out there.

The problem on a larger scale, for the channel at least, is that even in these perilous weather times, there are stretches when the worst things on the five-day forecast are some partly cloudy skies. The treacherous winter of 2014 follows a 2013 hurricane season in which no major storm made landfall in the U.S., a blessing for low-lying coastal areas and a curse for the network’s Nielsens. A run of pleasant weather is particularly bad news when competition comes not just from the local network affiliates but also the weather nerds on Twitter and the weather app in everyone’s pocket.

The network has had some success with Weather.com, which it launched in the pioneer days of the internet, one of the great unsung hedges in media history. The still-popular website—the one where you, and 8 million daily visitors like you, punch in your Zip Code to get the local forecast—has buoyed the company’s balance sheet, in part by taking a more sensationalist, anxiety-stoking approach. “Snow Panic Has Driven Weather.com Completely Insane,” joked Gawker—and that was last year, during a far milder winter. This season has brought a steady drumbeat of fear-inducing headlines (“Winter Shows No Mercy. Cold Is Back!”), red alert! banners heralding the latest advisory from the National Weather Service, and shameless click-bait (“Young Mom Found Dead in Snow-Covered Car,” “20 Ways to Pop the Question—Outdoors”). The website may now even be more valuable than the network, which is cold comfort for the TV people.

The predicament has occasioned something of an identity crisis at the Weather Channel. Like History and A&E, other niche channels, it’s experimenting with reality series, and like its cousins in cable news, it’s also betting on the power of personality, hoping Sam Champion has the magnetism to hold on to viewers for longer than it takes to catch a forecast, choose a sweater, and flip away. And it’s redefining what constitutes a weather story, looking for ways to engage viewers on those days when the roof isn’t about to blow off. In one recent series of segments, a correspondent interviewed shelter dogs hoping to become the channel’s official “Weather Therapy Dog,” which will be dispatched to areas hard hit by storms to comfort victims. The winner was a shepherd mix named Butler.

“That’s one heck of a lake effect!” Tom Niziol exclaims, to no one in particular. He’s just finished a live update on the storm barreling toward the South, but as a native of upstate New York, he always has an eye on Lake Ontario. Niziol—rhymes with drizzle—is another recent addition to the Weather Channel staff, but where Champion is buff and bleached blond, Niziol is bald, bespectacled, birdlike. During the 25 years Champion spent on air at ABC, becoming arguably the most recognizable face in weather (and surely the only one with an indie-rock band named after him), Niziol was sitting behind a desk at the National Weather Service’s Buffalo bureau, studying snow. Before he started at the Weather Channel in 2012, he’d never even been on television.

Niziol mans the so-called expert desk, a workstation in the heart of the newsroom that bristles with monitors displaying weather data. A telestrator allows him to illustrate for viewers the movements of cold fronts and low-pressure systems using an electronic pen, which he flips into the air and catches between takes.

In a winter of endless snow, Niziol has quickly become a fixture of the network’s severe-weather coverage. He’s also helped develop one of its most controversial recent experiments. In 2012, the Weather Channel began naming winter storms, a practice the National Weather Service had previously reserved for hurricanes—and previously reserved for itself. The thinking was that naming is a powerful tool for disseminating information about dangerous storms. No more anonymous nor’easters, said the Weather Channel. Meet, for instance, Winter Storms Iago, Orko, and Q—named, respectively, for the Othello villain, the Basque god of thunder, and, for some reason, the Broadway express train.

Niziol’s old colleagues at the National Weather Service weren’t amused, issuing a sternly worded memorandum prohibiting personnel from using the names in any NWS product. The internet-using public, by contrast, found the whole thing hilarious. This year, the Weather Channel has chosen to use Greek and Latin names, which gives the practice a patina of science. “Dorky,” tweeted Stephen King when Winter Storm Hercules bounded into New England in early January. A few weeks later, another storm paid a visit to the Northeast, this one named Janus, after the Roman god of transitions. Redditors gleefully posted screen captures of a Weather Channel graphic that had inadvertently obscured the J in Janus, and a thousand jokes about the crappy weather were launched.

Niziol stands by the utility of storm-naming, but there was a perception, among the weather community and viewers alike, that it was a thinly veiled effort to brand the weather, to turn weather systems into tempestuous reality-TV stars. It played into an existing concern that the Weather Channel has abandoned its core mission of delivering smart, sound forecasts in favor of airing whatever would get viewers to visit the channel, regardless of the conditions outside.

It was perhaps after watching one of the more questionable episodes of Freaks of Nature—a show that offers breathless profiles of men like Heinz Zak, an Austrian who defied the elements by slack-lining across a blustery alpine pass in a Tyrolean hat—that executives at DirecTV took the drastic step of dropping the Weather Channel. The bitter dispute is ostensibly over a penny, a reported one-cent increase, from $.13 to $.14, in the price per customer that DirecTV pays the network to carry its programming. But DirecTV has also argued that what viewers want from a weather channel isn’t Teutonic daredevils. They want to know the temperature outside. To prove that point, DirecTV started sending a new weather channel to its customers: a just-the-facts-ma’am product called Weather Nation.

On January 28, as Weather Channel correspondents are setting up across the Southeast, two young men in ill-fitting three-button suits are broadcasting on DirecTV channel 362—the Weather Channel’s old slot—from what looks like a dimly lit junior-college AV room. Between forecasts, they cut to a static map of temperatures across the country accompanied by elevator music heavy on alto sax.

No one, in other words, could accuse Weather Nation of having too many bells and whistles, though it does still have some kinks to work out. As the Weather Channel’s general counsel recently noted in a mischievous letter to the FCC, Weather Nation hasn’t yet mastered the art of closed captioning. Consider this update on conditions in the Midwest:

“That’s going to be the next system that spreads across the Chicago area, perhaps up towards Flint. As we head through the weekend, some impressive snow totals. May make for some tricky travel conditions.”

Which Weather Nation transcribed thusly for the hearing-impaired:

BAFFLING TO ME THEN NEXT IS DOWN THAT SPREAD DECRIES THE CHICAGO AREA AND SOME ORANGE FLAMES AS WE HEAD TO THE WEEKEND SOME NYMPH RESTAURANTS THE SUN MAY MAKE FOR SOME FREAKING TRAVEL CONDITIONS.

By the time Sam Champion takes the air at 5 p.m., it’s clear that the storm the Weather Channel has christened Leon is more than just a weather story. Roads that were congested at midday are now choked closed. School buses are marooned in the ensuing snarl, and several schools in the metro-Atlanta area will end up sheltering kids overnight; stranded parents will take refuge on the floors of Home Depot or CVS. The situation is so dire that Diane Sawyer decides to lead her broadcast with the storm, if apparently at the last minute. “We are here in Washington, D.C., for the president’s State of the Union address,” she says, “and one thing is certain tonight, this union is in the grip of a deep freeze.”

Champion kicks off his block of live coverage by checking in with Weather Channel reporters dispatched into the field. Reporting live from the Low Country is Jim Cantore, the popular, macho meteorologist who has set up near the College of Charleston. As he delivers his update, a piercing howl is heard off-camera, and, a moment later, a young man flashes into the frame, running toward Cantore as if to maul him. Without breaking eye contact with the camera, the meteorologist lifts his right leg at precisely the moment of impact, delivering a knee to his attacker’s solar plexus and sending him careening out of the shot, buckled over in pain.

I only catch up with the clip later, after it’s gone viral and become the subject of a skit on Jimmy Kimmel. By the time Cantore is fighting off stir-crazy undergrads on live TV, I’m attempting to make it to the airport before they run out of anti-icing fluid. “You better get the hell out of here,” Champion had told me when the first flakes began to fall. I should have trusted his forecast: I-75, which would normally be buzzing with rush-hour traffic, is instead a frozen wasteland littered with helpless Optimas, Altimas, and other cars purchased for their moon roofs, not their traction control. Drivers floor it trying to ascend the slightest incline, then run out of gas from the futile effort. Southerners who haven’t watched Champion’s snappy taped segment on how to drive in the snow are pumping their anti-lock brakes and steering against the skid like the winter-weather novices that they are.

I’m one of the lucky ones—I’ve hitched a ride with two New York–based web designers in town for a meeting with Weather.com. Like me, they were trapped at the Weather Channel headquarters, but they knew a driver hardier than most who was willing to pick us up in his SUV if we were game to hike a mile to the interstate, sparing him the even-worse conditions on the side roads. His truck makes quick work of the accumulating snow, but every quarter-mile or so, my companions and I are obliged to disembark, run out onto the road, and join the roving bands of Good Samaritans helping to get stuck cars unstuck.

Weather Channel people often talk of having had a formative childhood experience with the elements. Jim Cantore marveled at the snowpack of his Vermont boyhood; Sam Champion found his calling after tornadoes leveled the town where his grandparents lived. Jogging up the snow-hushed interstate, a municipal bus fishtailing in my direction, I experience in equal measure the wonder and terror of their childhood brushes with nature, and it occurs to me that this is what the Weather Channel offers: a first-person experience, the thrill of being there. An app can’t tell the weather story in all its apocalyptic glory—not yet, at least.

Such are the epiphanies one has while inhaling the exhaust of a Ford Fiesta spinning its tires on an ice patch, the elevated musings that are said to precede an acute attack of snow rage. We’ve been on the road now for four hours. We’re about halfway there.

*This article appeared in the March 10, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.