For more than three years, Democratic Senator Jeanne Shaheen and Republican Senator Rob Portman have been cooperating on a bill to improve energy efficiency standards. They carefully assembled a wide coalition, ranging from conservative business lobbies to liberal environmentalists, and trimmed away any remotely controversial provisions, leaving a series of modest-size but worthy reforms that helped business save money by reducing energy use. It appeared headed for passage, and even had bipartisan House sponsors. Then Monday the bill suddenly died. It died for reasons that were initially mysterious, but which turn out to clarify not only the legislation’s fate but the broader reason why national politics, in the form Americans wish it to exist, is dead and can never return.

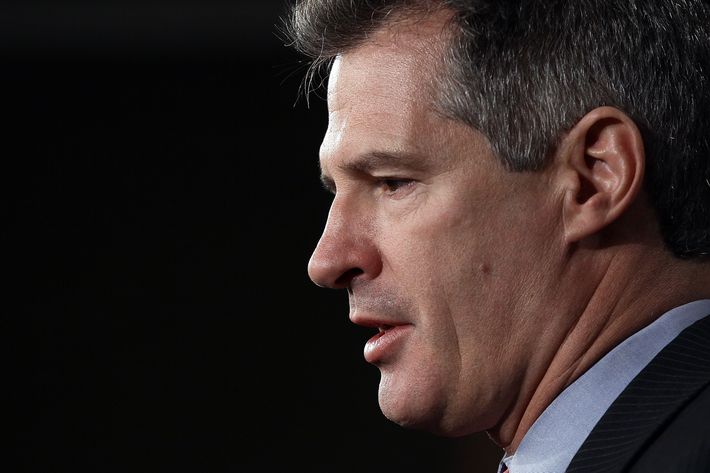

The proximate cause of the legislation’s demise was the demand by Republican Senators to hold votes on controversial amendments on issues like approving the Keystone pipeline and preventing new regulations on power plants. Obviously, attaching divisive amendments to a bill that was painstakingly written to avoid controversy is going to fracture its coalition, and so it did. The reason Senate Republicans decided to fracture the coalition for an energy bill everybody seemed to like, Sabrina Siddiqui and Ryan Grim report, is that Scott Brown asked them to. Brown is running against Shaheen this November, and Republicans — especially would-be Majority leader Mitch McConnell — want Brown to beat Shaheen because they want to win a majority.

Brown needs to deprive Shaheen of the afterglow that would come from shepherding a (now rare) bipartisan bill through Congress. And, indeed, when Senate Republicans killed Shaheen’s bill, the New Hampshire Republican Party immediately highlighted its failure to attack her:

Senator Shaheen has called the Shaheen-Portman Energy Efficiency Bill her ‘defining’ legislation. But after its defeat, Senator Shaheen doesn’t have a single legislative accomplishment to run on as she seeks re-election. It’s time to end Jeanne Shaheen’s failed tenure in the Senate and replace her with a responsible Republican who can get results for New Hampshire.

For a voter paying close attention to the Senate’s machinations, this makes little sense: Republicans are arguing that their torpedoing of Shaheen’s bill proves Shaheen is a legislative failure. But few voters follow politics so closely, and even those reading detailed coverage of the bill’s failure would quickly get lost in an arcane procedural dispute that putatively caused its demise.

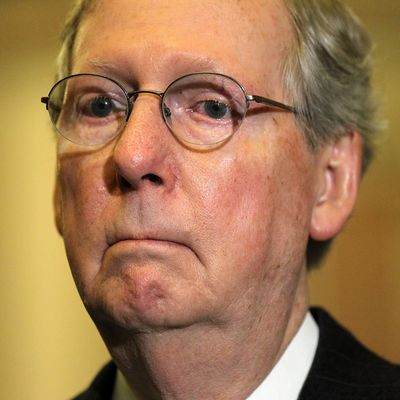

This dynamic — that voters do not follow the details of legislating, but form crude heuristic judgments based on the two parties’ ability to agree — is the essential strategic premise that has guided Republicans since 2009. Mitch McConnell has, astonishingly, explained this strategy openly on at least two occasions. “It was absolutely critical that everybody be together because if the proponents of the bill were able to say it was bipartisan, it tended to convey to the public that this is O.K., they must have figured it out,” he told the New York Times in 2010. The next year, he told the Atlantic Monthly:

We worked very hard to keep our fingerprints off of these proposals. Because we thought—correctly, I think—that the only way the American people would know that a great debate was going on was if the measures were not bipartisan. When you hang the ‘bipartisan’ tag on something, the perception is that differences have been worked out, and there’s a broad agreement that that’s the way forward.

You can call this cynical, but McConnell is actually doing what we expect our politicians to do. An election system is supposed to be competitive. The two parties have very different ideological goals and understand that gaining power is necessary for them to bring policy closer into line with how they define the public good. The main difference between McConnell and leaders who came before him is not that he’s a worse human being — though I find his policy goals abhorrent — but that he’s more strategically shrewd.

McConnell has not merely outmaneuvered other politicians in his strategic acumen, he has likewise surpassed the whole Washington Establishment. The near-total absence of bipartisanship has not escaped anybody’s notice — it is the subject of frequent and even obsessive commentary. The failure of the parties to find agreement is routinely attributed to a series of tactical or communications missteps or the decline of the Georgetown dinner party scene or other variations of magical thinking. It is unable to grasp the underlying strategic incentives of two parties.

The framers of the Constitution didn’t expect elected officials to sacrifice their own power. They designed a system intended to align the interests of those officials with the public good. The trouble is that they did not anticipate the rise of political parties. Decades of ideologically diffuse parties — a Democratic coalition cobbling together urban liberals and Southern segregationists, a GOP joining Rockefeller progressives with McCarthyite reactionaries — masked this fundamental problem. In the modern system, single-party rule is the only condition that should be expected to produce major legislation. Americans want the two parties to get along, but they fail to understand that this requires one of them to acquiesce in its own defeat.