The fallacy that produces the most wrong political predictions is the assumption that present trends will continue indefinitely. Even the most immutable political facts are subject to change. And yet the status quo, a stubborn gridlock pitting a Republican House against a Democratic presidency, is entrenched in an unusually deep way. The GOP House stands almost no chance of falling — because Democrats have grown reliant on voters who don’t turn out in midterms, because Democratic voters are packed inefficiently into overwhelmingly Democratic districts, and because Republicans gerrymandered the map. At the presidential level, Democrats continue to benefit from a growing demographic advantage. On top of those familiar trends, a new one is beginning to take shape: a strong pro-Democratic bias in the Electoral College.

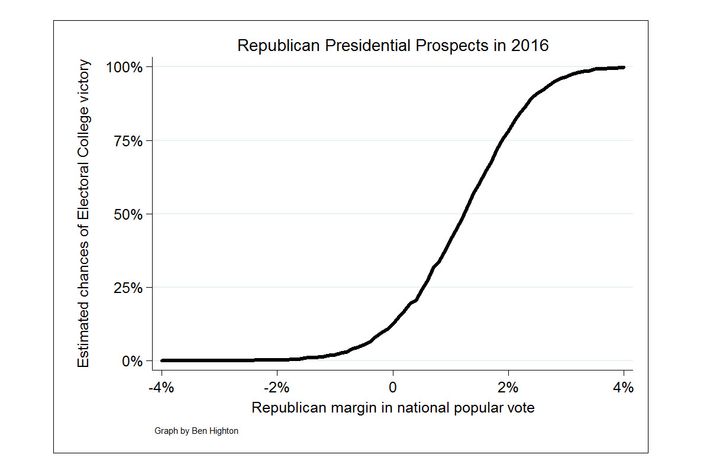

Ben Highton, a political scientist at the University of California-Davis, has identified a trend that hardly anybody in Washington has noticed yet. In a pair of blog posts, Highton persuasively makes the case that the Electoral College has taken on a strong pro-Democratic tilt. That is, the states in the center of the Electoral College distribution lean more strongly Democratic than the electorate as a whole. How heavily? Highton has a chart:

According to his figures, Republicans would need to win the popular vote by about 1.5 percentage points to stand an even chance of winning the presidency. Even if they win the popular vote by two percent, their odds of winning the election would not top 75 percent. That is a steep Democratic bias.

The Democratic swing-state advantage appears all over the map, but its locus is probably the quintessential swing state of Florida. Since the run-up to the 2012 election, electoral analyst Nate Cohn has been tracking Florida’s steady lurch toward the Democratic party (see here, here, and here).

Florida’s rapid transformation has been masked by a pair of contradictory trends reflecting the state’s unusually heterodox political culture. Nationally, states with high numbers of Latino voters have trended Democratic, turning Nevada from a swing state to a Democratic-leaning one, and New Mexico from a leaning Democratic state to a solid one. Meanwhile, southern white voters have deepened their longstanding march toward the Republican party during the Obama years.

Florida has plenty of both southern white people (especially in its northern panhandle, which borders and culturally resembles Alabama) and Hispanics. The Latino vote is growing very fast in Florida. In 2000, Cohn points out, white voters cast 78 percent of the votes in an almost even election; in 2012, they cast just 67 percent. Mitt Romney only managed to keep the race there close because the white vote tilted so heavily in his party’s direction. But the rapid growth of Florida’s nonwhite electorate is continuing. On top of that, it’s possible that a candidate like Hillary Clinton could win back at least some of the white voters who disdained Obama.

Florida encapsulates the demographic trap encircling the Republican Party. They have deeply alienated Latino voters there, and the first step in the party’s elites’ grand strategy to gain a hearing with them — taking immigration policy off the table — is nearly dead. Republicans right now would need a major electoral wave to win Florida, and without Florida, they have almost no viable path to prevail in a close election.

And, of course, they could always catch that wave with a well-timed recession or some other major political boon. Failing that wave, they are staring down a presidential electorate where the odds look increasingly dire. They can block legislation from the House for years to come without getting a whiff of the Oval Office; indeed, that very thing may well transpire.