What do liberals believe about the current disaster in Iraq? One thing most of us believe is that the United States should stay the hell out. But another thing liberals believe with even greater conviction is that advocates of the last Iraq war should not participate in the current debate. The Atlantic’s James Fallows argues that Iraq war hawks “might have the decency to shut the hell up on this particular topic for a while.” Slate’s Jamelle Bouie, writing in the second person, instructs Iraq hawks, “Given your role in building this catastrophe, you should be barred from public comment, since anything you could say is outweighed by the damage you’ve done.” Washington Post columnist Katrina Vanden Heuvel, MSNBC host Rachel Maddow, and many others have reiterated the point. This meta belief about who should be allowed to argue about Iraq, more than any actual argument about Iraq itself, has become the left’s main way of thinking about the issue.

Advocates of shut-the-hell-up have different ideas for who should be placed within the cone of silence. Fallows would include all 2003 advocates of war (a sweeping group that would include me, Fred Kaplan, John Kerry, Hillary Clinton, not to mention a handful of Fallows’ colleagues):

Others seem to have in mind only members of the Bush administration. Still others would apply it only to members of the Bush administration who are also neoconservative, oddly exempting non-neocons like John Bolton or Condoleeza Rice:

The most frequent justification for STHU is “accountability.” There should be a price for being wrong. I supported the war in 2003, which I now regret, and it is entirely reasonable to think more skeptically about my arguments. (I do; I consciously decided to write less frequently about foreign policy as a result.) Interviewers soliciting the opinions of Iraq War architects should certainly disclose and clarify that their subjects have an interest in salvaging their reputation.

But STHU advocates aren’t making a generalized case for retroactively scrutinizing the arguments made by politicians and public intellectuals. They’re arguing for accountability applied to the singular event of the 2003 Iraq War.

Most Democrats in Congress opposed the Gulf War, warning of Saddam Hussein’s fearsome, World War I–style fortifications and citing 45,000 body bags as an indication of the likely U.S. death toll — predictions that turned out to be wildly incorrect. Why shouldn’t anti-Gulf war Democrats – that is, the vast majority of Democrats — have been excluded from subsequent foreign policy debates? If your answer is “because people died — Iraq,” then then you’re not arguing that pro-war arguments should be ignored because they’re analytically wrong, you’re arguing they should be ignored because they’re inherently morally suspect, regardless of accuracy.

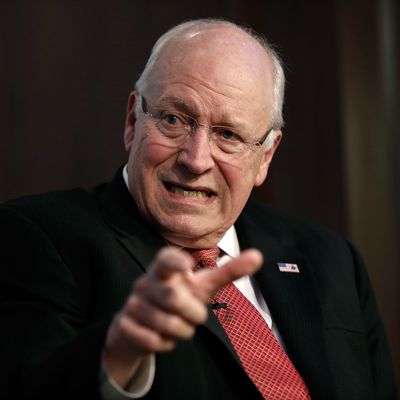

When you’re trying to set the terms for a debate, you have to do it in a fair way. Demanding accountability for failed predictions is fair. Insisting that only your ideological opponents be held accountable is not fair. Nor is it easy to see what purpose is served by insisting certain people ought to be ignored. The way arguments are supposed to work is that the argument itself, not the identity of the arguer, makes the case. We shouldn’t disregard Dick Cheney’s arguments about Iraq because he’s Dick Cheney. We should disregard them because they’re stupid.

The trouble with STHU is not that it will succeed in depriving Dick Cheney, or anybody else, of a forum to propagate his beliefs about Iraq. The trouble is that it is currently preventing liberals from thinking about Iraq. Liberals are treating the current Iraq debate as if it is literally the same thing as the 2003 debate. Paul Waldman, in a column headlined “On Iraq, let’s ignore those who got it all wrong,” riffs:

And the rest of the neocon gang is getting back together. Here’s Lindsey Graham advocating for American airstrikes — and I promise you that if the administration does in fact launch them, Graham will say they weren’t “strong” enough. Here’s Max Boot saying that what we need is just short of another invasion of Iraq: “U.S. military advisers, intelligence personnel, Predators, and Special Operations Forces, along with enhanced military aid, in return for political reforms designed to bring Shiites and Sunnis closer together.”

Providing air strikes, aid, and intelligence coordination to a government that has requested it may or may not be a good idea. (I’m undecided, leaning against.) It is not the same thing as invading and occupying a country. Indeed, the ideological fault lines of the current debate aren’t even the same. Former Bush staffers and Iraq War champions David Frum and John Bolton have argued for a policy of non-intervention. Should they be ignored because they got Iraq wrong in 2003? The Center for American Progress is advocating air strikes. Should it be heeded?