The Obama administration’s announcement today of new regulations on power plants does not mean that it has saved the planet. It does not even mean that we have necessarily bought time to save the planet. It means, simply, that Obama has done everything within his power to fight the most urgent crisis of our time. That is to say, he has put in place a climate-change policy agenda that is likely, though not assured, to be regarded as a historic success.

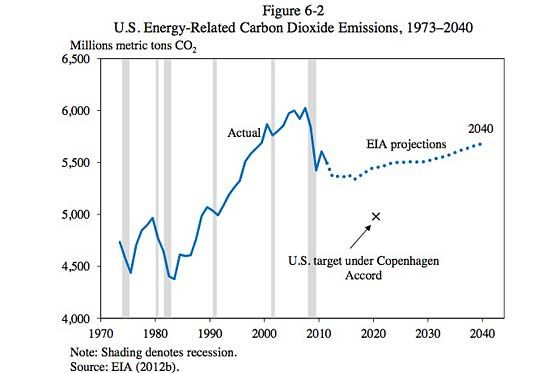

The shape of the challenge is captured by this chart, which appears in the Economic Report of the President:

The x represents the target that today’s regulations are intended to hit. The x, specifically, would mean that the United States has reduced its carbon dioxide emissions by 17 percent below 2005 levels. That is the reduction target the United States promised at the 2009 Copenhagen summit. If achieved, most observers believe it would give the United States a strong (though far from certain) chance to persuade China and other countries to enter an international carbon treaty.

Such a treaty would not end or even contain the threat of climate change for all time; it would, however, contain the damage and buy time for a transition to a de-carbonized energy economy. The cuts are necessary but not sufficient to sign the treaty, and the treaty is necessary but not sufficient to spare future generations the worst disasters.

You may notice that the blue line, representing U.S. carbon emissions, has fallen sharply under Obama. That drop both overstates and understates the success of Obama’s environmental record. It overstates it because a majority of the drop is accountable to changes for which Obama bears no responsibility. The shale gas revolution replaced coal with much cleaner gas; younger Americans drive much less than older generations; and the recession caused Americans to use less energy.

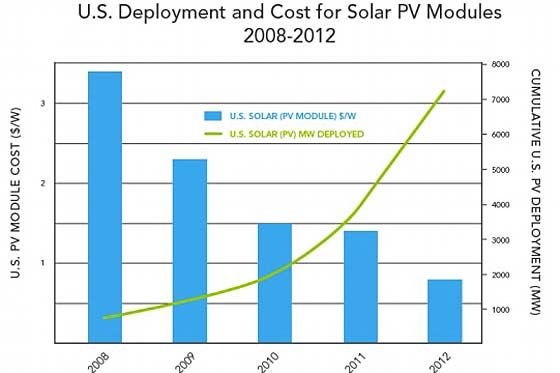

On the other hand, it understates Obama’s contributions, the impact of which are only beginning to appear. Obama’s Environmental Protection Agency has essentially banned the construction of any new coal power plants and imposed stringent new fuel-economy standards that will dramatically shrink the carbon footprint of American transportation. The stimulus has spurred advancements in wind and, especially, solar energy, the latter of which is in the midst of a revolution of affordability and growth:

Regulating currently existing power plants is the final piece of the agenda, completing the task Obama set out for himself at the outset of his presidency.

Obama originally hoped to accomplish this task — to hit the x — by passing a sweeping cap-and-trade law through Congress. The failure of that bill in 2010 produced bitter recriminations, many of which laid the blame on the president’s alleged lack of commitment. “Obama never fully committed to the fight,” complained the New York Times editorial page; he showed “no urgency on the issue, and little willingness to lead,” concluded Rolling Stone. An entire genre of green angst parsed the administration’s culpability. The most detailed indictment was a long New Yorker story explaining how “the last best chance to deal with global warming in the Obama era, was officially dead,” and which concluded with the haunting suggestion that “Barack Obama was the James Buchanan of climate change.”

The common thread running through nearly all these denunciations was the assumption that a cap-and-trade law would have amounted to a successful environmental legacy for Obama. That was the premise of my story last year explaining how Obama had already accomplished, and would likely continue to accomplish via regulation, what he had failed to pass through Congress. In a post defending my story, environmental analyst David Roberts noted, “Apparently some folks are quite upset about it and think it’s terrible.”

The lingering conclusion that Obama simply did not care about the environment made many of my fellow liberals doubt that Obama would ever take such a risky step. “I think this has the proverbial snowball’s chance in hell of actually happening, but don’t let anyone tell you Obama has no options,” wrote Matthew Yglesias. The failure of the EPA to immediately produce regulations prompted Joe Romm to conclude Obama was “delaying action.” When Obama’s budget did not include power plant regulations — which are not a budgetary item — Ryan Lizza wrote, “Nothing in his new budget follows through on that promise. And if that doesn’t, what will?” in a column headlined, “Has Obama Already Given Up on Climate Change.”

Obama’s climate agenda may well ultimately fail. If it does, it will be because it was thwarted by actors he cannot control: All five Republican-appointed Supreme Court justices may nullify his proposal, or a future Republican president may dismantle it, or the governments of China and other states may decide not to enter an international treaty. A president cannot save the planet. But it can no longer be fairly denied that Obama has thrown himself entirely behind the cause.