I asked Bill de Blasio if he thought something fundamental had changed, if nearly two decades of decreasing crime in the city was a permanent improvement. “You can’t say anything is irreversible,” de Blasio said. “I think we can say it is structural, however. Meaning, over three different mayors and five or six different police commissioners, we’ve seen steady progress. And a lot of the tools we have now — Compstat, focused deterrence, gang intervention, some of the technology we have — that’s forever, that’s not going away … We’ve made a lot of progress, and I think we can deepen it, if we get the relationship between police and community right again.”

That was last August, when de Blasio was a candidate. Last week Mayor de Blasio got his first big reminder of just how difficult the reality of public safety is, and how much depends not on objective tools but on the judgment of individuals. Eric Garner resisted arrest. Officer Daniel Pantaleo wrapped his right arm around Garner’s neck and wrestled him to the ground. The responsibilities aren’t equal, but the sum of those two choices was a tragedy — Garner died.

Now the fallout from that Staten Island sidewalk scuffleis testing de Blasio. His relationship with the NYPD is still new and unsettled. Things got off to a bumpy start in February with City Hall’s intervention in the arrest of a Brooklyn minister. Many cops welcome de Blasio’s de-emphasis of stop-and-frisk — but just as many believe he’s anti-cop, based on last year’s campaign rhetoric, and the transition to amorphous new tactics has left much of the department off-balance. The enforcement of marijuana laws is a muddle. And the mayor is tangling with the PBA over a new contract, offering no retroactive raises for two of the years it would cover, similar to the deal accepted by other municipal unions. So the tone of de Blasio’s reaction to the Garner incident is being closely watched by cops.

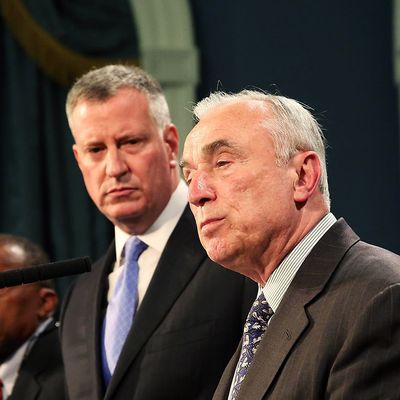

The dynamic between de Blasio and his police commissioner, Bill Bratton, is also still in the formative stages. Bratton, in some ways, has a tougher job than he did during his first tour of duty atop One Police Plaza. Instead of the all-out 1990s offensive to break a crime wave, Bratton is trying to keep the numbers low while following de Blasio’s mandate to do it with a softer touch. At times the two men seem to be out of synch: Bratton appeared more eager to hire new cops than his boss, and his unabashed love for the Hamptons makes it look like Bratton didn’t get the income inequality memo.

Style points won’t matter, of course, if Bratton can get the substance right — and de Blasio has a tremendous amount riding on his police commissioner. Achieving the tricky balance between respect for civil rights and vigilant law enforcement frees the mayor to pursue the rest of his agenda. And while the Garner incident is not to be minimized, other, less dramatic events — the spike in shootings, the weekend vandalism spree in Central Park — are worrisome, both to the health of the city and to the mayor’s political prospects. The fact that someone scaled the Brooklyn Bridge undetected on de Blasio and Bratton’s watch doesn’t exactly inspire public confidence, either.

The police commissioner spent Tuesday afternoon on Staten Island meeting with community leaders. That should help dial down emotions. But Bratton’s belief in “broken windows” policing is unflinching, which guarantees the debate over its effectiveness will continue when de Blasio returns from his vacation in Italy. Eric Garner’s funeral is today, and the issues raised by his death are very much alive.