I first heard about The Sex Cure in 1991 when I was 13 years old and my family had recently moved from Dallas to the picturesque, upstate village of Cooperstown, New York. Older adults there would make occasional, hesitant reference to a novel, published decades earlier, that revealed the town’s secrets under a thin fictional veil, but refused to say more. I got the sense that it had disrupted a lot of lives and caused a lot of pain — but that there was also a very interesting story there. The problem was figuring out what it was. It took me until 2005 to track down a copy of The Sex Cure — if you can find one on eBay now, expect to pay up to $500 for a paperback that once sold for 50 cents. Over the course of years, I pieced together the details of the scandal by talking to longtime residents, searching through microfilm and old lawsuits, and digging up newspaper clippings. Cooperstown, as all but a few people had forgotten, was once at the center of one of the best literary sex scandals of the 20th century.

In the modern American lexicon, “Cooperstown” is synonymous with the National Baseball Hall of Fame, which lives on Main Street. On Sunday, it will draw a bright flash of national attention as a robust class of six baseball greats is inducted into the Hall, accompanied by lots of celebrations, photo ops, and inflated prices — all in all, a welcome change after several slim years when all the best players were tainted by steroids. Like all Cooperstonians, I was grateful to have the Hall in town. I worked there after my freshman year in college, operating the projection room for a highly sentimental film about baseball’s history shown approximately a dozen times a day. But I was always aware of the flattening effects of Cooperstown’s, well, fame. This complex and unique little town was known to the world for one thing, and nothing else about it quite registered. I think that’s one reason I started becoming obsessed with the lost history of The Sex Cure, and began a novel, Love All, about the scandal and its legacy.

As it turned out, modern-day Cooperstown welcomed the resurfacing of this history. But for a long time, residents rarely spoke of The Sex Cure — it was a betrayal, a dirty secret. Despite reportedly having a first print run of 250,000 copies, the novel has all but disappeared. Today, it’s virtually impossible to find a copy. There’s no easy answer to the question of where all the copies went, but local theorizing holds they were bought up by Cooperstonians who wanted the book to disappear. I paid $100 for the copy I bought in 2005. Inside the back cover, I found a handwritten cast list — someone’s best guess at the real identities behind the characters in the novel.

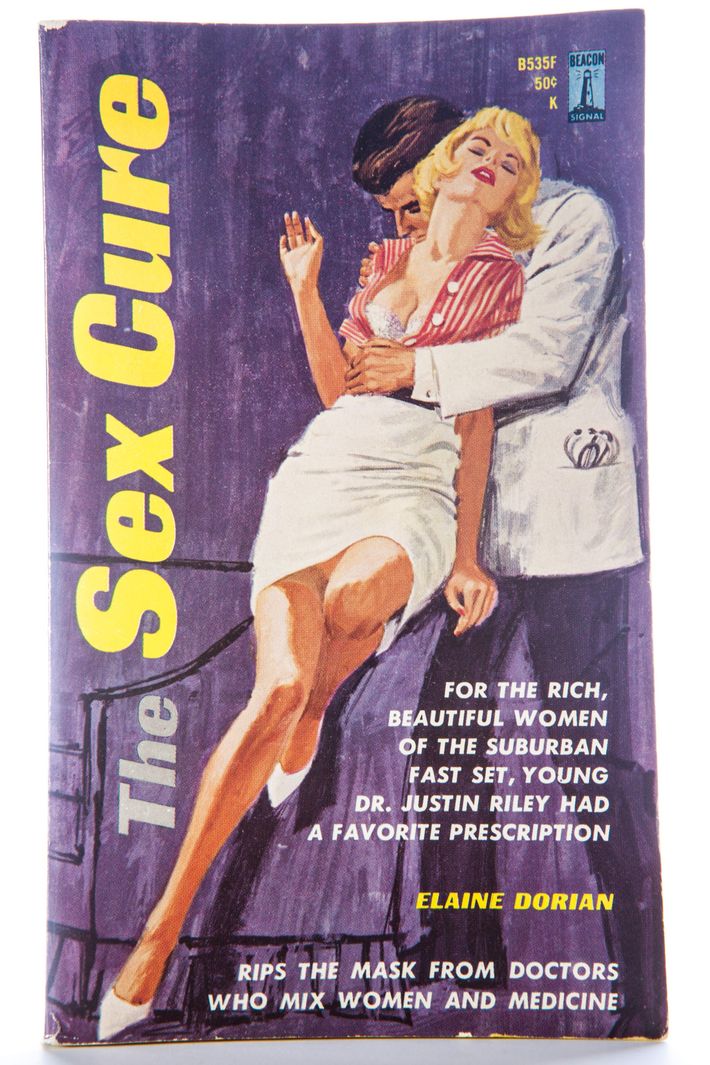

The Sex Cure saga began in 1961 when Isabel Moore, a 46-year-old pulp novelist who had written paperbacks like Love Now: Pay Later and Second-Time Woman under the pen name Elaine Dorian, moved to Cooperstown to spend time with her older daughter, Elaine, a show-horse rider who’d married a local man. Moore’s younger daughter, Pamela, was a writer like her mother: In 1956, at age 18, Pamela had published the best-selling Chocolates for Breakfast, a sexy coming-of-age novel about a 15-year-old girl’s precocious love affairs. (It was reissued last summer by Harper Perennial with a foreword by Emma Straub.)

Moore rented a house in the village, where she spent her days writing and her evenings mingling with the locals. This glamorous, accomplished woman — she had an Ivy League education, had written dozens of books, and had a set of Hollywood friends that included Cary Grant and Marilyn Monroe — was big news in a small town. People eager to impress her dished up their juiciest local gossip. Moore at some point decided to repackage this bounty of material as an exposé of Cooperstown using residents’ real names, or transparent pseudonyms. The Sex Cure painted a portrait of a village gone wild. Rampant extramarital affairs, illegal abortions, illegitimate children, rape — a scandal-monger’s fever dream of life in a well-to-do village.

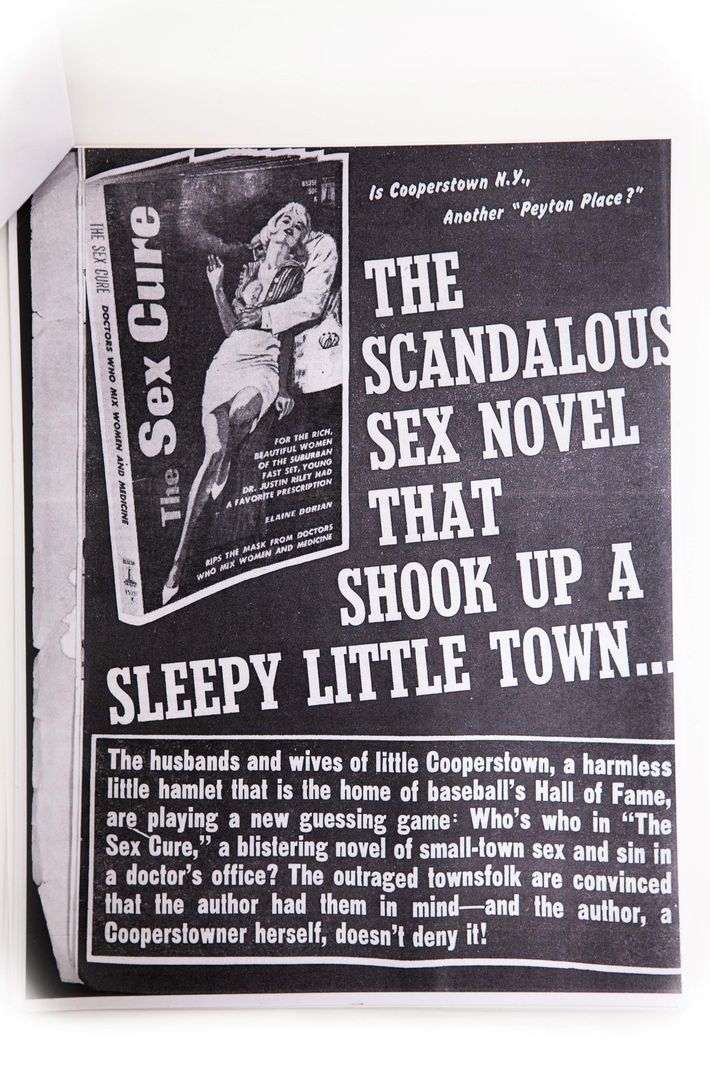

When the The Sex Cure was published in September 1962, Moore told the Utica Daily Press: “This book sounded like Cooperstown, and it was supposed to,” calling her novel Cooperstown’s Peyton Place in reference to the still-famous tell-all about Gilmanton, New Hampshire, that had come out six years earlier. “Mary Stevens Memorial Hospital,” owned by local landowner “Cyrus Stevens,” sounded dangerously like Mary Imogene Bassett Hospital, established by Cooperstown’s Stephen Clark Sr. — philanthropist, heir to the Singer Sewing Machine fortune, and founder of the Baseball Hall of Fame — whose family had altruistically supported the town for more than a hundred years. Moore described her character Cy Stevens as a “tyrant” ruling with an “iron hand,” and she sent a collective shudder through the village on page 100, when, in an apparent copy error, “Cy Stevens” simply became “Clark Stevens.” The 70-year-old Cy Stevens, whom Moore describes as “sexually impotent” with a heart condition, still wants women, however, “to fondle and possess and look at.” He pays a nurse from his hospital $100 to take off her clothes and sit on his lap, where she rocks back and forth until suddenly realizing Mr. Stevens has had a heart attack.

Clark’s wife claimed not to have read The Sex Cure and told the Utica Daily Press that she didn’t know anything about the book. “I just heard about it indirectly,” she said. “I don’t think it’s one I’d like to read.” If the Clarks were angry, they didn’t say so publicly. Not so with a Cooperstown resident who found her own name — with one letter changed — on the pages of the novel.

Mrs. June Dieterle, a local babysitter at the time, brought a $600,000 libel suit against Isabel Moore and her publisher, Universal Publishing and Distributing. In the The Sex Cure, Jane Dieterle runs a “baby farm” where she routinely administers “chloro-hydrate” to her charges so they stay asleep for long periods of time. When she’s not babysitting, Jane runs “an infinitely more lucrative practice of illegal abortions,” writes Moore, “for which she charged up to two hundred dollars.” The libel suit was reportedly settled in 1964 for an undisclosed sum.

Many prominent people in town suddenly found themselves tied to characters in Moore’s novel. From doctors at the hospital to mothers with young children, residents’ private lives quickly became the source of frenzied public discussion. Locals scoured the book and filled in its margins with the who’s who behind The Sex Cure. It was the stuff of ruined lives, of divorces, tarnished reputations, and severed friendships. Some people named in the novel were said to have packed up and left town.

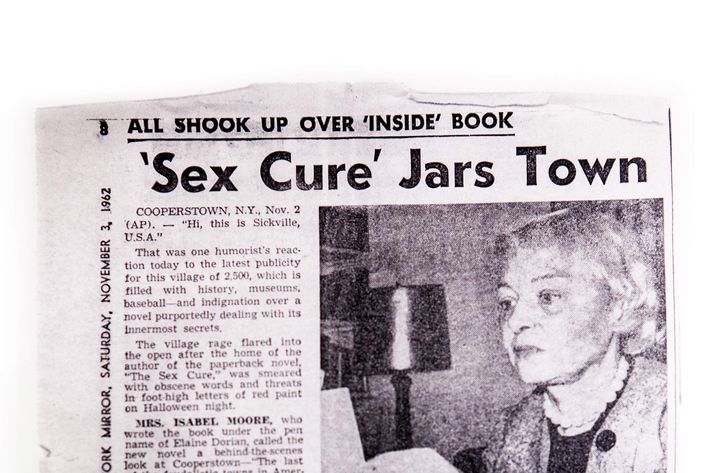

On Halloween night, fury escalated to the point where a mob gathered outside Moore’s Lake Street home and spray-painted it with obscenities and threats in an attempt to silence her and run her out of town. Moore had been tipped off by a friend in time to escape the mob, but the attack instead brought the scandal to a national audience. Overnight, reporters appeared from the New York Times and Associated Press, among many others. The Times ran a story with the terrifically understated headline,“Cooperstown Finds Itself in Sex Novel and Doesn’t Like It.” More told AP, “I think the town revealed itself as a sick town.” The village’s police chief said, “That book shook the town up real well.” All the attention reportedly spurred a second print run.

As a teen, when all I wanted was to fit in, I couldn’t get over the idea of an author risking alienation to write a slanderous novel about her neighbors. But Isabel Moore seemed to have a plan. As she said at the time, “Who knows? Maybe I’ve become a better attraction than the Hall of Fame.”

The mayor of Cooperstown refused to comment when asked by the Utica Daily Press about The Sex Cure’s relationship to the village, offering instead,“This is the kind of publicity Cooperstown doesn’t like.” The younger generation disagreed. A teenage girl in town admitted to the same reporter, “I’d sure like to read that book.” At local bookstores, wait lists for the novel reportedly ran more than 400 people deep.

Days after the Halloween attack, a construction company arrived on Lake Street to paint over the obscenities on Moore’s rental home, and though the police did find one can of red enamel paint at the crime scene, sending it to Albany for fingerprint analysis, many people had handled the can — including members of the police — and the culprits were never identified.

Moore was unrepentant about the book. In the Binghamton Press, she described her writing process as a formula of interspersing chapters about sex with chapters about topics including “the business world, society, retrospect, or what-have-you. But,” Moore admonished, “don’t forget the sex.” She wasn’t about to be bullied into leaving town. “This is good material for my next book,” she told the Utica Observer Dispatch. “My publisher is delighted.”

Callie Wright’s novel about the scandal, Love All, came out in paperback this month from Picador.