Derek Jeter Opens the Door.

<span>The retiring legend offers a photographer access to his private world—the first project in a new career that is all about control.</span>

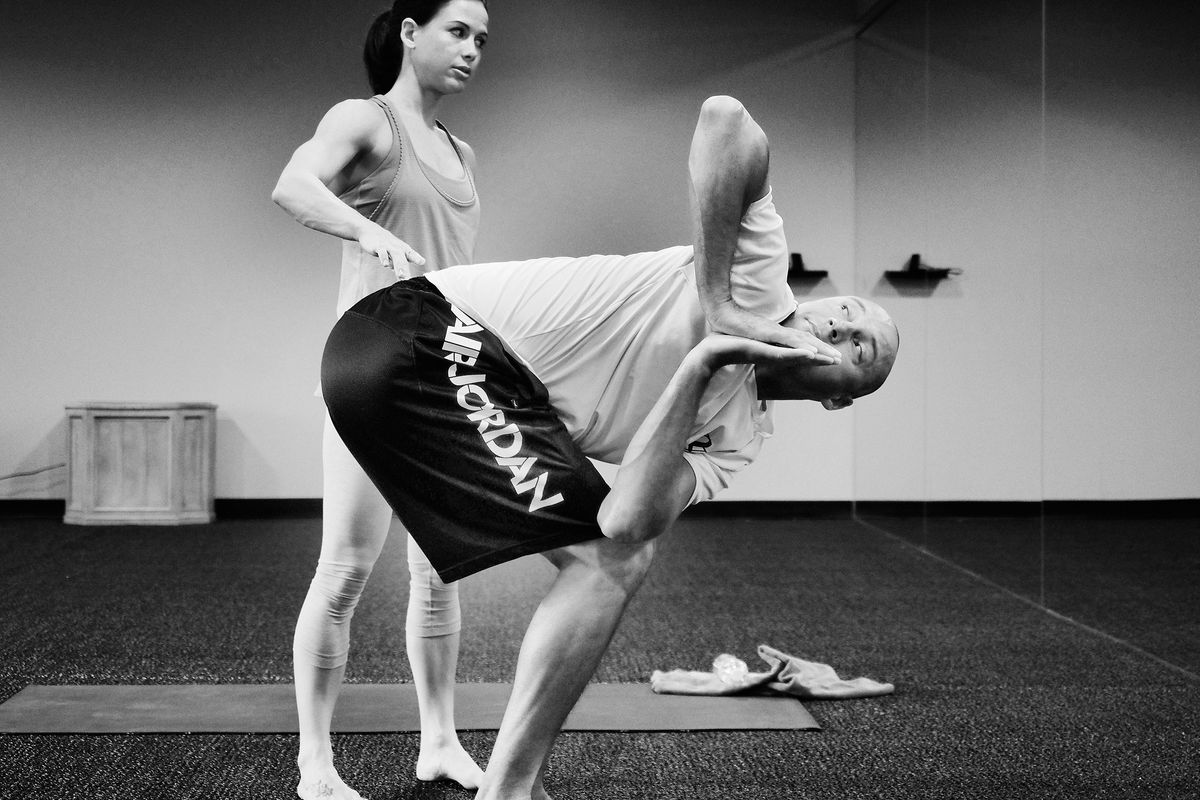

It’s a steamy Saturday morning, and Jeter is standing in the first-floor dining room of the brick 1830s West Village townhouse he’s renting. “Come on in,” he says. He’s wearing a gray, maize, and blue University of Michigan T-shirt in anticipation of his beloved Wolverines’ football game tonight against Notre Dame. At 40, he is ancient for a major leaguer, but up close he is leaner than he appears in uniform. With his shaved head, light-green eyes, and coiled serenity, Jeter could pass for a charismatic yoga instructor.

Instead, he is, of course, New York’s reigning sports star on its most glamorous team. And yet, despite being on our television sets seven months a year for the past 20 years, despite the regular appearances at charity events and a social life that seems to have included dating three-quarters of the Maxim Hot 100, he’s always felt just out of reach, available for all to adore but somehow still protected by an impenetrable, cannily constructed bubble of privacy. Opening the door to his home is a hint of a looming shift in Jeter’s life, and in Jeter, Inc.

Tomorrow is Derek Jeter Day at Yankee Stadium. It’s his latest stop on a cross-country farewell tour celebrating not just Jeter’s Hall of Fame–caliber playing career but his humility and rectitude off the field. Jeter announced in February, via Facebook, that he would be retiring after this season. Since then, he’s done a remarkable job of tuning out the impending end of his athletic life, at least publicly. At home, though, down to his final days in pinstripes, Jeter is by turns wistful, proud, funny, even a bit cranky. Mostly he seems relieved. “No more off-seasons,” he says. “It’s just over.”

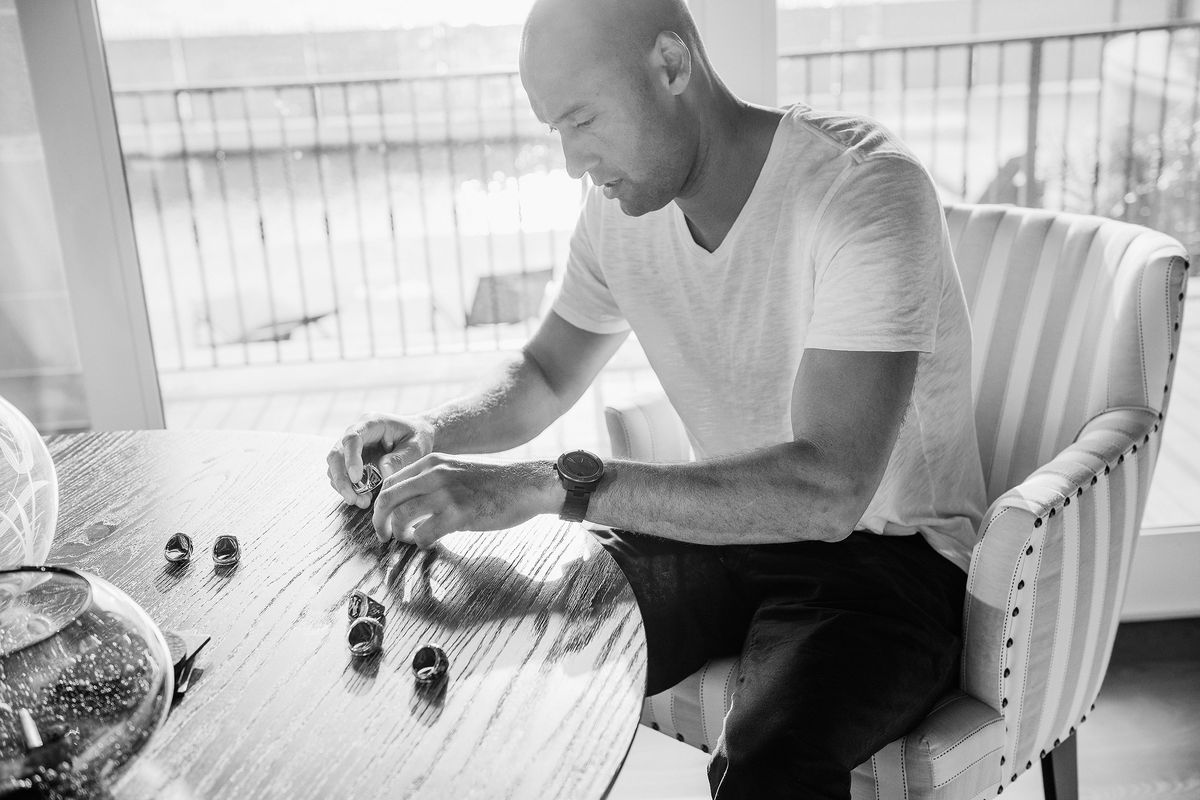

He has no interest in the traditional jock afterlife: coaching or commentating or getting fat. Instead, he’s launched a publishing imprint at Simon & Schuster. A children’s book comes out September 23, followed in October by Jeter Unfiltered, a collection of evocative, documentary-style off-field photographs by Christopher Anderson—and a significant departure for the privacy-conscious icon.

Jeter Publishing, however, is only the first step. In a media landscape where stars are increasingly taking ownership of the means of production—Oprah Winfrey rose from talk-show host to media conglomerate, Dr. Dre went from producer to music mogul, and Beyoncé runs a management company—one option for Jeter is an ambitious media play. After two decades of being content, he’s intrigued by the possibility of becoming a multi-platform content provider. His business pursuits will likely be varied, but they will all be characteristically Jeter: He will be the one in charge.

There is the rustle of keys. The front door opens. It’s Chef Debbie, Jeter’s personal cook, back from the farmers’ market with a load of groceries. “Do you have to work down here?” Jeter asks as she opens the refrigerator. “We’ll go up, so we won’t bother you.” With that, we’re climbing the stairs, dark-brown wood with black steel railings, past a colorful painting of Miles Davis, one of the few visible decorative touches. “Oh, great, I get a tour,” I say.

Jeter’s response is immediate and firm. “I wouldn’t say tour,” he says. “I’m letting you go up one level.”

The numbers rank with those of baseball’s all-time greats: the sixth-most hits, the five championship rings, the 19th-highest offensive WAR. Then there’s the surplus of dramatic plays in high-pressure situations, including a crushing leadoff home run to doom the Mets in the 2000 World Series and the game-saving “flip” of a wild throw in the 2001 playoffs against Oakland. Yet what has truly separated Jeter on the field, and elevated him in the eyes of his peers, is something that can’t be captured in stats and highlight reels. He’s radiated a confidence, a command, that has lifted not just his own play but that of his teammates. His signature stroke—a line drive the opposite way, to right field—is an act of both iron will and unselfishness. It’s hard to say what’s more remarkable: that Jeter has been able to sustain such consistent control for 20 years under the New York spotlight, or that it was there from the moment he fully arrived onstage as a 21-year-old rookie in 1996.

“Even though it was his first year in the big leagues, Derek was a finished product as a person,” Joe Torre, the former Yankees manager, says, still a bit amazed all these years later. “Very mature, responsible.” Torre credits Jeter’s parents for a psychological grounding that sounds simple, but isn’t. “He felt comfortable in his own skin. Other players need to be validated. Derek doesn’t need the attention.”

Jeter’s mother nicknamed Derek “Old Man.” “Our parents say Derek kind of strutted and had a lot of confidence from when he was really, really young,” says Jeter’s sister, Sharlee, who is five years younger. “I think the nickname came from the first time he went off to school and he had his little briefcase and he was all dressed up in a little suit.” The first book from Jeter Publishing is called The Contract, and it’s a lightly fictionalized account of the eight-point bargain that young Derek signed (No. 1: “Family Comes First ”; No. 3: “Maintain Good Grades”) each year. The penalty for violations was losing baseball time.

Jeter is still in many ways that self-serious kid, though he’s now full of adult opinions. Yet he recognized early in his Yankees career that opacity was a shield and an asset. Jeter’s blandness with the press isn’t from a lack of intelligence. “It’s exactly the opposite,” says David Cone, a Yankees teammate of Jeter’s for six seasons. “It’s a very defined approach to control the message.”

He learned that often the best way to deflate a story is to ignore it. The Post once claimed that after sleeping with women, Jeter would leave a gift basket of signed memorabilia in the car taking the “conquest” home. He’s avoided commenting on the item for three years. But he’s still annoyed. “Like I’m giving them signed baseballs and pictures of myself on the way out! Who comes up with a story like that?” He laughs, incredulous. “It said the reason people found out was because I gave the same girl the same basket and I had forgotten I’d given her one—like there are so many people coming through I forgot!” Even if Jeter were cheesy enough to have handed out souvenirs, he’s far too careful to have made that kind of mistake.

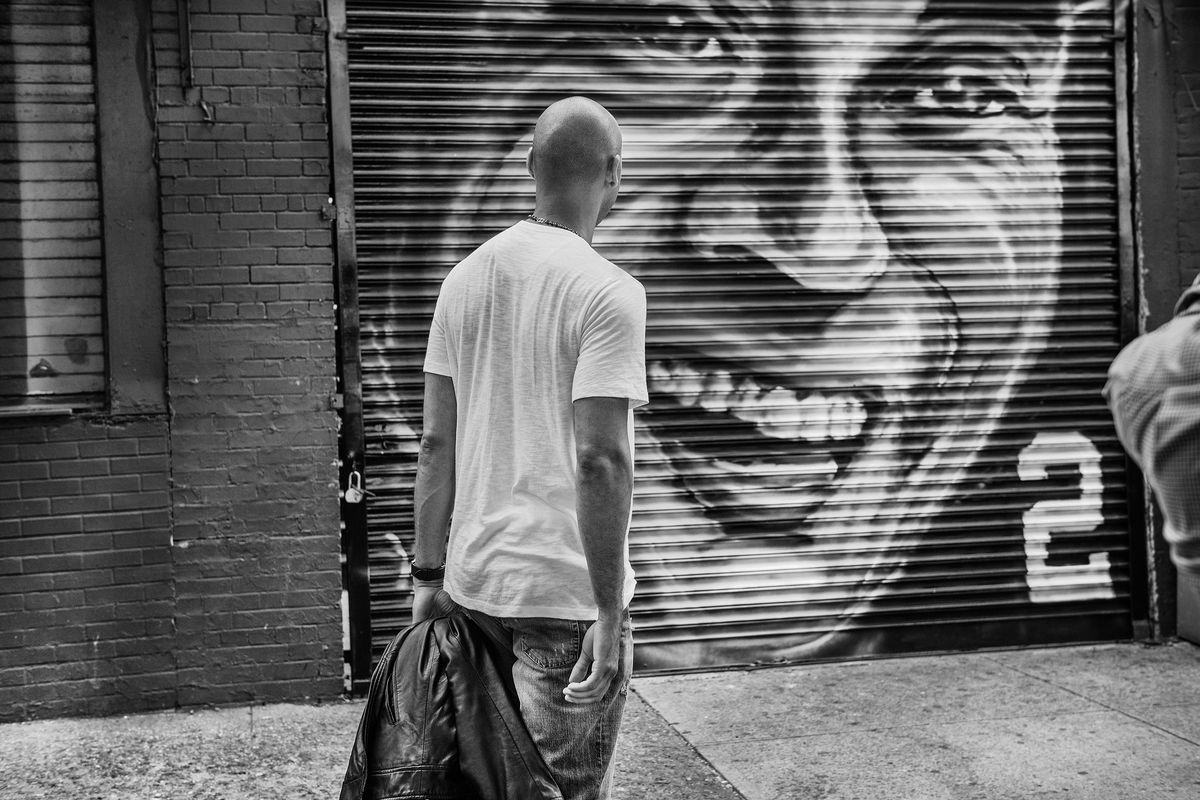

Good behavior combined with savvy strategizing—Ian O’Connor’s biography, The Captain, describes how Jeter asked party guests to check any cameras or cell phones when entering his home—has enabled him to both stay out of the gossip rags and cash in on endorsement deals. Don’t get him wrong: Jeter has had plenty of fun, and he’s grateful for all the opportunities his life has provided. Yet fame and fortune have costs. One photograph in Jeter Unfiltered catches him in silhouette staring out the open window of a car. It was a Sunday afternoon, after a game at Yankee Stadium, and Jeter was stuck in traffic on the West Side Highway opposite the weekly free-form barbecue festival in Riverside Park. “It made me think about how I haven’t been to any summer barbecues for over 20 years,” Jeter tells me. “I’m looking forward to having one next summer.”

“Derek is a guy who has a genuine desire to stay connected to the real world,” says Anderson, who spent parts of seven months following Jeter (he’s also this magazine’s photographer-in-residence). “He loves looking at people as he drives around town. I wonder if that’s because there’s a bit of a metaphorical glass window between him and the rest of the world.”

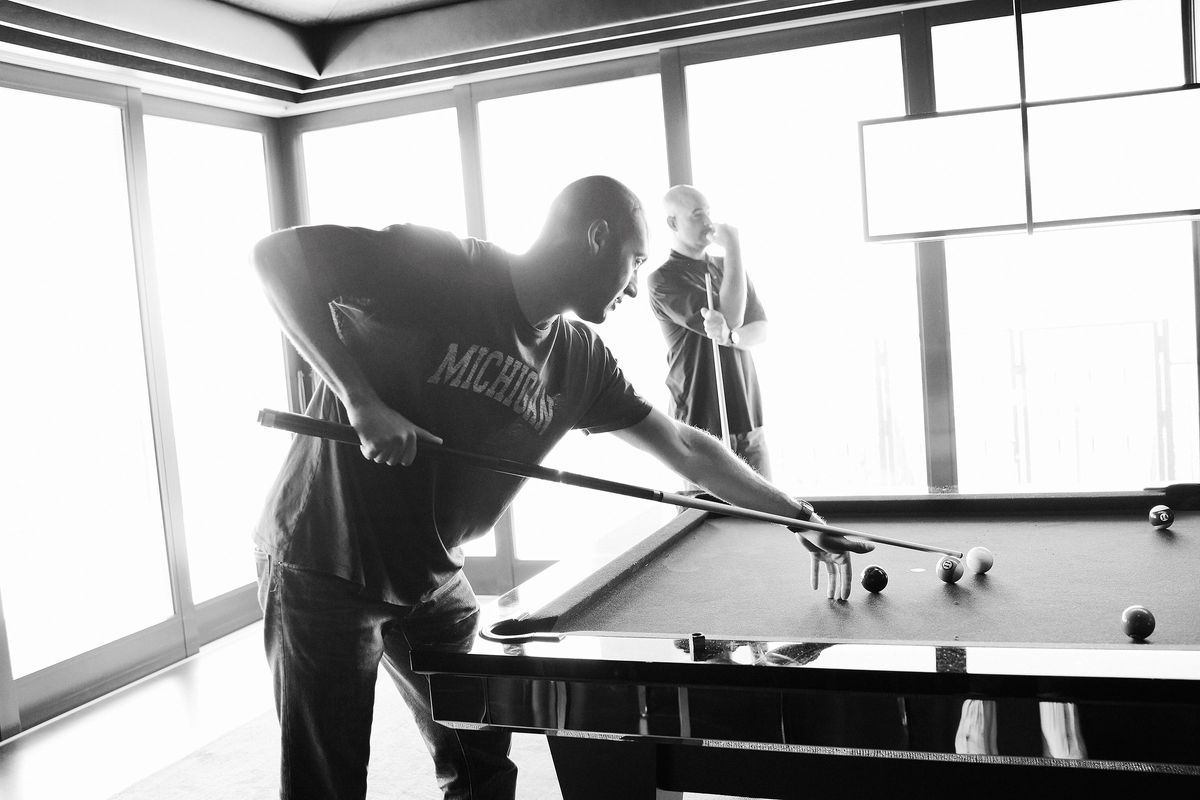

At first Jeter was ambivalent about the photo project, intending the portraits to stay private. “His words were, ‘I don’t want to be that guy with my own photographer or film crew following me around,’ ” Anderson says. “But he wanted to be able to document, even for his own family, this last year and this time in his life. Maybe he had some sense of history in his mind, too.” Jeter’s Tampa mansion contains plenty of art books. He’d been looking at Thomas Hoepker’s famous pictures of Muhammad Ali, and Walter Iooss Jr.’s pictures of Michael Jordan off the court. “He recognized that somehow, someplace, pictures from this period in his life would be worthy to create,” Anderson says.

Louise Burke, the head of Simon & Schuster’s Gallery Books division, pushed for Unfiltered to be a book. Jeter established few limits other than authenticity. “He’s uncomfortable doing anything that isn’t natural to him,” Anderson says. “I kept looking for opportunities to get him physically interacting with the city—‘Let’s ride the subway.’ But Derek said, ‘That would never happen. It’s not because I’m too good for the subway, but the two times I rode it I thought I was going to get pulled apart.’ ”

Anderson shot Jeter in Tampa, Chicago, and New York. He came away with a deep understanding of Jeter’s complicated relationship with privacy and an appreciation for how levelheaded Jeter has stayed. “Other celebrities get mobbed for autographs, but it’s significantly different watching Derek on the street,” Anderson says. “In New York, the public has a sense that they own him. ‘He is ours. He is the captain of the New York Yankees. And the Yankees are ours.’ ”

Jeter’s commitment to the game has created another kind of distance. “If not for baseball, he probably would have been married by now,” Sharlee Jeter says. “The schedule is the schedule, so it’s very hard to have a personal life that’s structured.” Sharlee has a 3-year-old son, Jalen, whom Uncle Derek adores, but she laughs when envisioning her big brother becoming a father. “Derek thinks that with a kid, today you’re going to be potty trained, this is what you’re going to eat and what times you’re going to eat. That’s just how he lives his life,” she says. “It’s going to rock his whole world.”

The second floor holds the living room, but it doesn’t feel as if there’s been much living going on in Jeter’s New York house. He takes a seat at one end of a customized poker table covered in dark-blue felt with Jeter’s personal Nike logo at the center in white. The walls are mostly bare; his World Series MVP trophy is nowhere in sight, nor are any family photos or keepsakes, or any sign of Hannah Davis, Jeter’s 24-year-old model girlfriend.

“I was over by the U.N. for ten years, and sold that, and I’ve been down here for a little while,” Jeter says. “I like this—you almost feel like you’re not even in the city. No high-rises, not a lot of traffic. It’s a whole neighborhood, a whole new feel.”

Still, he will vacate the rental after the season’s over. For all of his hold on a city’s baseball memories and emotions, Jeter, who grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan, has never really been of New York. For most of his career, he has considered Tampa his hometown, especially since he built a $12 million, seven-bedroom mansion there that’s been nicknamed “St. Jetersburg.” Sometimes, when the Yankees don’t have a game, Jeter will fly to Tampa just for the day.

“In New York there’s a lot of attention off the field, a lot of distractions,” he says. “My job on our team all along is to try to limit distractions and try to keep it about the game. I think a lot of times players get in trouble when they’re asked questions and they think they have to find a way to answer it. If you ask me a question and I say, ‘I don’t know,’ there’s really no follow-up.”

Pretty shrewd, but it’s also one of the reasons writers say Jeter can be a boring interview. “If I was giving them headlines all the time, I wouldn’t have been here for 20 years,” he says. “But they ask boring questions. Give me a different question, and I’ll give you a different answer.”

Okay: Did you vote for Obama or McCain in 2008? “I don’t have to get into politics,” Jeter says sharply. “I voted for Obama. But another thing I realized is my job is as a baseball player, so I stick with what I know the best.” He’s far more eager to discuss his Turn 2 Foundation, which has channeled $19 million into creating programs that teach “healthy lifestyles” to kids. “That’s very, very important to us as a family,” Jeter says, “and it will continue beyond my playing days.”

The serial tributes, as he’s visited stadiums for the final time this season, have forced him to reflect a bit. He misses the original Yankee Stadium. “It was a different feel,” Jeter says. “The new stadium, it’s second to none—all the amenities. For the players, it really doesn’t get any better. The old stadium, if you were at the stadium, in the stands, the only place you could see the game was in your seat. Now there’s so many suites and places people can go. So a lot of times it looks like it’s empty, but it’s really not. The old stadium, it was more intimidating. The fans were right on top of you.”

He misses George Steinbrenner. “We had a great relationship,” Jeter says. Steinbrenner’s children, led by his youngest son, Hal, run the franchise now. In 2010, during contract negotiations, management dared Jeter to go somewhere else as a free agent. “They’re not around as much as the Boss was,” Jeter says. “The Boss would pop in frequently during the course of the season. Hal and Hank, they don’t really come in too often. They might be at the stadium, but they don’t come through the clubhouse. The Boss, we weren’t playing good, he’d come through the clubhouse, look you up and down, and shake his head.”

Other characters he doesn’t seem to miss at all. Alex Rodriguez was a close friend at the beginning of Jeter’s career. Then he mocked the Yankees shortstop in an interview with Esquire and the relationship went into a deep freeze. In 2004, A-Rod was traded to the Bronx, and the melodrama spiraled until January, when his suspension from Major League Baseball for using performance-enhancing drugs was finalized.

There’s no shortage of theories about Rodriguez’s problems.

Jeter glares. “This is not an Alex story.”

Most baseball questions, though, elicit a sigh before Jeter answers. Oh, he will keep pouring every ounce of energy into every inning until at least the final pitch of the Yankees’ final regular-season game, on September 28, in Fenway Park. He loves baseball still, but he is weary of the grinding devotion it demands. And he can see the chance to exercise different parts of his brain. “This has been parts of 20 seasons—23 professionally,” he says. “I’ve been playing baseball since I was 5 or 6 years old. I’ve been on a schedule, pretty much, since I was in eighth, ninth grade. I look forward to not doing that.”

A broken left ankle in October 2012 sidelined Jeter for most of 2013 and accelerated his thinking about the inevitable end of his playing days. He wouldn’t let the injury force him to retire—a grueling rehab allowed Jeter to return this spring—and he would control the announcement of his exit. The year off also gave him time to start considering ideas for his next career. Jeter’s one explicit goal is to own a Major League franchise. “No former player has owned a team in baseball,” he says, his voice rising with a competitive edge. “In basketball, M.J., obviously. But not in baseball.”

Michael Jordan has been a mentor to Jeter, and a sponsor of sorts through Nike. Another, more entrepreneurial model is Magic Johnson, who is a part owner of the Los Angeles Dodgers but also heads an entertainment company with a social mission. Jeter, however, seems to want to develop something wholly his own. During his career the internet exploded, and the already blurry line between on- and off-field coverage has been nearly erased. “There’s pretty much no privacy whatsoever anymore,” he says. Yet Jeter, the city’s preeminent jock star all that time, is the shining exception. He has come out the other end of the fame machine with his sanity intact, with a valuable brand—and with an invaluable education in modern media.

In March 2013 his business advisers approached Gallery Books about a deal to publish both adult and children’s books. He wants Jeter Publishing to be substantive and to range beyond sports—in early September, it bid, unsuccessfully, for the rights to Ray Kelly’s autobiography. “I know people have always been interested in what I do, not only on the field but off the field,” Jeter says. “Just because I choose to keep a majority of my life private, I still get the fact that content is important. There’s a lot of interesting people out there, and interesting stories, and I want to be able to share them.”

Jeter could convert his rarefied experience as a marquee subject of journalism and publicity, plus his credibility with other star athletes, into a vehicle to deliver “inside” access to other players. Unfiltered feels like the preview of a platform for curated intimacy, where narratives could extend beyond print to the web or TV. “One of the goals for Jeter Publishing is to find formats that are suitable for personalities who want to reveal more about themselves without feeling too exposed,” Jeter says. “I have ideas coming. We’re still crossing the t’s and dotting the i’s. I think I’ve learned a lot as the subject of content. I don’t think I’m an expert. I need to finish what I’m focused on now before that next chapter. But yeah, the seed has been planted … I’m nervous and excited. I’ve never been in a place where I didn’t know exactly what I was doing next.”

Right now, though, he’s got to get to the ballpark. The number of times he’ll make this trip is rapidly dwindling. He steps down the front stairs, slips on a pair of black aviator shades, and heads toward the local Starbucks for his regular grande red-eye. Then it’s around the corner to the garage where his Mercedes is waiting; Jeter drives himself. As he strides along the narrow West Village slate sidewalk, he squeezes past a guy walking a small dog and offers a friendly nod, just like a civilian. The man turns and resumes walking the dog, then does a double take. But Derek Jeter is gone.

*This article appears in the September 22, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.