The 5:30pm Lucky Streak Greyhound was nearly empty yesterday as it pulled out of Port Authority Bus Terminal on its way to Atlantic City. Years ago, the service would have been full of gamblers from New York, drawn to the blinkering promise of Atlantic City casinos. It made stops at Bally’s, Caesars, Showboat, Tropicana, Trump Taj Majal and Trump Plaza, disgorging those unlucky enough to count themselves lucky.

On the last night, the final hurrah, of the Trump Plaza, a gargantuan boardwalk staple since it opened in 1984, the Lucky Streak ferried only eight souls, rattling in their seats like spare change. The casino would cease operation at six the following morning, and approximately 1,000 people would never show up for work there again. It is the fourth Atlantic City casino to shut down this year amid plummeting revenue: The Atlantic Club folded its hand in January; Showboat sunk in August; and Revel, another of the big time casinos and the newest, died at only two years old after an infancy of neglect. There is talk that Trump Taj Mahal might shut down soon. Any of my fellow passengers hoping to spend the night at the Trump Plaza would be disappointed — its 612-room hotel was already closed.

Tony, last name “From Brooklyn”, a heavy set man with cherubic face, committed mullet and a number 80 Jets jersey, was one of the eight southbound shades. He has been going to Atlantic City since 1978. “I come down about 45 times a year,” he said, shrugging, “I guess I like the action.” He’d been to the Trump Plaza but wasn’t mourning its loss. “I never liked it,” he said, “the casino is upstairs. You have to take an escalator!” No, Tony preferred Bally’s. “They’ve got that new restaurant by Guy Ferrara. The prices are high but the food is outrageous.” Across the aisle from Tony, a woman in a pink velour jump suit played Candy Crush and sang loudly along to the bachata on her headphones. “Mi corazon,” she warbled until the bus driver, responding to an elderly Pinoy man yelling “Shut up! Shut up! Shut up!” crossly took to the PA: “No singing. You can sing when you get to the casinos.” But of course she couldn’t hear him. She was singing too loudly.

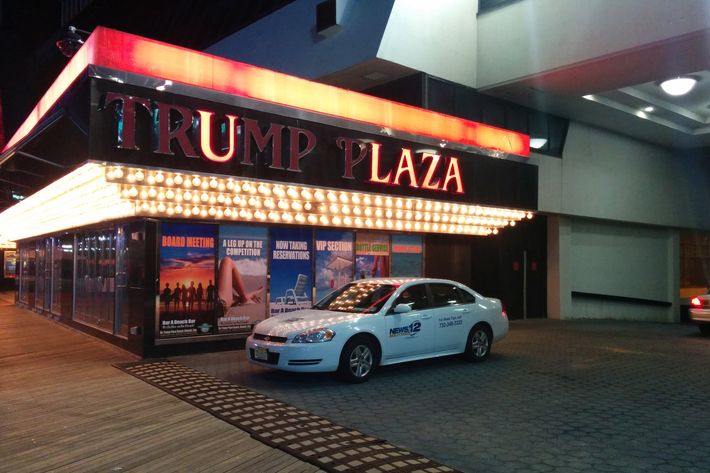

When we got to Atlantic City, the silhouette of the Trump Plaza was all but invisible in the darkness. Instead, the once bombastically bright Trump Plaza signs floated like disembodied vowels, disemboweled bodies. Their letters had been allowed to burn out. One read _ _ U _ _ _laza, and another _rump Plaza. It was a Wheel of Fortune puzzle sliding into pathos.

Inside, the All Day Buffet was brightly lit but closed, along with all other Trump Plaza operated restaurants. (Sbarros and the Rainforest Café remained open.) The carpet — so much carpet — smelled of smoke and dust. Three gamblers, two men and a young woman, ascended the elevator as it left the buffet behind. Were they sad to see the casino close? “No,” said the woman. “No one wins up in this bitch.”

At the Trump Plaza, there was enough sadness to sink an ocean of smiles. Miles, literal miles, of slot machines clanged but no one listened, no one came. I counted about twelve players on the floor in the non-smoking section. But in the smoking section, where 30 years of cigarette smoke clung to every loop of crummy carpet, every crevasse of every machine, where ash had been ground into the stools so they too seemed made of ash, the Trump Plaza didn’t seem quite dead yet. Brian Lechak was there with his wife, up from Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. They both wore sweatpants, Atlantic City t-shirts and lanyards heavy with casino reward cards. “I learned how to play $1 Blackjack here,” said Brian, “That’s rare. No one does that anymore. This is our farewell tour to the Trump Plaza.”

Most of the blackjack, poker and baccarat tables had neither dealers nor players. The green felt was worn but well-cared for, the baccarat wheel encased in plastic. But at one end, close to the now closed Trump One service center, there was an enclave of survivors. Many of the dealers had traded their handsome white shirts with gold cuffs and collars for Philadelphia Eagles jerseys. The Eagles game played, alongside a video of INXS’s Need You Tonight, on multiple TV screens.

Tina, a tiny blackjack dealer with a broad smile, wore the forest home jersey. “We’re not allowed to talk to media,” she averred when asked how she felt about the closure, but she couldn’t resist. Stacking the eight decks of cards, though I was the only player at the table, in a smooth seamless routine, Tina said, “I came here 26 years ago as a young girl. I’m walking out that door tomorrow a grandmother of three. These people,” she said, choking up as she looked around, “are my family. And the closing of the Trump is like a death in the family.”

Before Tina was a stack of worn out Trump Plaza chips, all perfectly smooth and slightly sticky. By tomorrow they’d be worthless plastic. But tonight they still have value. Tina, like many of the other workers, doesn’t know what she’ll do after Tuesday night, when many former employees will be meeting at The Hi-Point Pub in Absecon, NJ, to hold a sort of wake for the Plaza. “You’ll hear some stories there,” she said.

By far the most lively area in the whole place was Jezebel’s, a small lounge in the back of the casino floor. There was a reunion underway of the old stage crew. Jules Lauve III, who used to run the 700-seat theatre, reminisced about the days when Sammy Davis Jr. packed in the crowds. “It was the creme de la creme,” said Lauve, a man with kindly grey eyes that twinkled behind a thick pair of glasses. Lauve had long moved on from the Trump Plaza — he now had a consulting firm in South Norwalk, Conn., but he had come down to see old friends.

Richard Ucci sat across from Lauve. “This man,” he said, “he was my best friend. After my first marriage, he let me stay with him for a month.” Ucci is a piano technician with a lot of stories. He tells one about a very famous crooner who played the Trump Plaza in 1987, “He was in a bad mood because there was a story in the tabloids that he had given some lady herpes,” said Ucci. “Turns out she already had herpes.”

The booze at Jezebel’s was running out and eventually the whole stage crew decided to visit the theater one last time. They stood on the stage, confetti still scattered about. “See that partition,” said Jules, “we built that for Sammy Davis Jr. He used to love to walk on it.” A heavy set man cried, “Who wants to walk the crossover one last time?” then disappeared behind the scrim. “Someone should take a picture,” cried a voice, so Jules, always the leader, gathered the old hands together. They raised their glasses and cried, “To the best of the best!”

Later, much later, in the evening, in the morning in fact, Jules was wandering the boardwalk outside the Trump, misty eyed and a little tipsy. “This stretch used to be the best in the world.” he said, gazing down the flood-lit avenue of wooden slats and plaster façades “ Now, it’s just shit,” he sighed. “My dad had a saying: There’s a time to sow, a time to grow, and a time to go. Now is the time to go.”

Jules turned to walk back to his hotel room at Caesars. leaving behind the stage he managed, and the family he loved. He was once a big man at a big casino but now the casino was closed and Jules, as he made way home, grew smaller and smaller against the curtain of the night sky.