The argument of my story in this week’s magazine is that completely legitimate concerns about the safety of professional football players, and the NFL’s handling of domestic abuse, have metastasized into a moral panic. The role of football in American life — which is much broader, and perhaps more fundamental, than our spectator relationship with pro football — has come under a withering scrutiny that blends together cultural disdain with putative concern for public health. Dan Diamond has written a rebuttal to my story that, upon closer examination, actually serves as further evidence for its premise.

Diamond disputes three points. Let’s take them in order.

1. Is high-school football dramatically more dangerous than other sports, or only slightly more dangerous?

The most important dispute here is that Diamond claims my article “misconstrues the facts” about the concussion risk faced by high-school football players. Diamond tells his readers that, according to my article, “concussions aren’t a problem in high school athletes.” I do not make that claim anywhere.

Instead, my article concedes that football players face a higher risk of concussion than any other sport, but the difference is incremental. Here is how I put it:

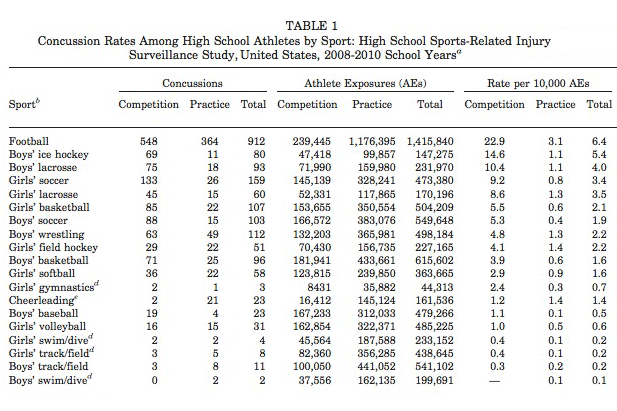

A recent study found the odds of sustaining a concussion during a football practice or game (6.4 times per 10,000 athletic events) runs ahead of sports like girls’ soccer (3.4 times per 10,000), boys’ lacrosse (4), and ice hockey (5.4). In other words, the concussion risk in boys’ football is about twice as high as in girls’ soccer and about one-third higher than in hockey. This is an incrementally higher risk — on the order of driving an older car versus a newer one, as opposed to the elevated risk of, say, taking a job as a drug mule over becoming a librarian.

Diamond disagrees. He argues that football players have a dramatically higher risk of concussion:

“Concussion rates are much higher in football than in other high school sports,” Dr. Dawn Comstock told me. …

And according to Comstack’s data, which tracks millions of athletes, football’s clearly, dramatically more risky for the brain.

“For every 10,000 kids playing in a football game this Friday across the country, we expect 33 of them to sustain a concussion,” Comstock told me. …

And according to Comstack’s data, which tracks millions of athletes, football’s clearly, dramatically more risky for the brain.

Now, here is the funny thing. The data I cited in my article is also co-authored by Dr. Dawn Comstack. Here is the table comparing the concussion rate of various sports:

The column on the right, showing the total number of concussions per 10,000 athletic exposures, is exactly as my piece describes. Football, as I wrote, has the highest concussion risk, at 6.4 per 10,000 events. Next comes hockey at 5.4, boys’ lacrosse at 4.0, girls’ soccer at 3.4, and so on. Football, as I wrote, is incrementally more dangerous, but not dramatically so.

So, what is his argument, exactly? Diamond uses a different study, also authored by Comstack, that yields slightly different results. But that small difference does not account for the source of our disagreement. Instead, Diamond frames the data in a different way. One thing he does is that, rather than compare football to the next-most-dangerous sports, as I do, he compares it to sports that sit lower on the list, like soccer and basketball. He is not refuting my point in doing so — he is merely selecting a more favorable comparison. My article points out that football is only incrementally more dangerous than the second, third, and fourth most dangerous high-school sports. Diamond says no — it’s a lot more dangerous than the seventh and tenth most dangerous sports. I suppose he’s entitled to frame the facts as he sees fit, but keep in mind that his substantiation in no way supports his charge that my article misconstrues the facts.

Diamond frames the data in a second way that actually is misconstruing the facts. Instead of comparing the overall danger of football to the overall danger of other sports, he compares the danger in games. Here is how Diamond puts it:

In comparison, for every 10,000 boys playing in one high school soccer game, there are 12 concussions. For every 10,000 boys playing in one high school basketball game, there are 4 concussions.

Why does that word, games, matter so much? Because football has fewer games (“competition,” as the chart puts it) than almost any other sport. Players are more likely to get a concussion during a football game than a soccer game, but there are fewer football games. That is why I used the column on the right, the total, which reveals the combined concussion risk of games and practices.

Diamond’s games-only measure is better if you’re only worried about the risk of a player getting concussed during an official game and completely indifferent to the risk of a concussion during practice. Is there any rational reason to care about game concussions but not practice concussions? Not that I can think of.

And if you look at the total risk, rather than selectively using the games-only risk Diamond uses, it is clear that my description is accurate. To believe, as Diamond writes, that “football’s clearly dramatically more risky,” you have to believe that 6.4/10,000 is far greater than 5.4/10,000, rather than incrementally greater.

2. What is the cause of the NFL’s domestic-violence problem?

Diamond writes, “Chait’s wrong to so quickly dismiss players’ arrest rates: The NFL domestic violence rate is quite high, disturbingly so.” This disagreement may be even more strange, because I do not dismiss the elevated domestic-violence rate in the NFL. As I wrote — and Diamond quotes it! — “It is true that NFL players are likelier to be arrested for domestic violence than for other crimes.” Indeed, my article is explicitly not a defense of the NFL at all, and it witheringly criticizes the NFL’s handling of domestic abuse.

The debate between us is not whether NFL players have elevated rates of domestic abuse. It’s why. Diamond makes two arguments: One, the culture of football makes men violent toward their spouses. And two, brain damage caused by concussions may make them violent.

I instead suggest two different reasons: Football attracts more violent people, and NFL players’ use of steroids and human growth hormones makes them more violent. I did not make any definitive claim in my article that the reasons I suggested are the real causes and that Diamond’s are not, though I did suggest my account is “more likely.” Diamond does not present any arguments on behalf of his hypothesis or against mine. He merely portrays my article as downplaying the problem of domestic violence in the NFL.

3. Does football have a positive role in socializing boys?

Diamond concedes that he disagrees but cannot substantiate his belief. (“Perhaps that’s true. Perhaps it isn’t. There’s no longitudinal study of whether football is a viable intervention for young men who otherwise would become violent offenders.”) I agree. My essay did not make any definitive claims about this. Rather, it suggested that football’s critics approach the question with more modesty, considering the possibility that this old-fashioned institution still has some legitimate role in modern life, or at the very least trying to understand what the thing they’re condemning looks like from the inside.

This is significant because my article originally quoted Diamond making the sort of sweeping, immodest claim I was arguing against. In a previous column, he asserted that the NFL’s domestic-violence problem “could be associated with more than the culture of football.” The reason I quoted this line is that, as I wrote, it “took entirely for granted” that the culture of football causes domestic violence in the first place. That is to say, he is combining a shaky understanding of the sport’s actual risk with deep but completely unsupported prejudices about its sociological effects. In other words, he is providing an example of exactly the kind of thinking I set out to describe.