After weeks of hearing dire reports about the spread of Ebola in West Africa, many Americans were understandably terrified when the first Ebola case was diagnosed in the U.S. on Tuesday. But the main message from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s first press conference on the anonymous Dallas patient wasn’t to look out for symptoms or stop shaking hands; the organization just wants to keep Americans from panicking. “The bottom line here is that I have no doubt that we will control this case of Ebola so that it does not spread widely in this country,” said Thomas Frieden, the agency’s director.

While Americans should still be concerned for those in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, they definitely don’t need to break out the surgical masks at home (particularly because Ebola isn’t airborne). Here’s what the CDC is doing to prevent the epidemic from spreading at home.

It’s helping the U.S. maintain a strong public-health infrastructure.

In Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, more than 3,000 people have died, and there are 6,500 reported cases of Ebola. The disease, which is transmitted through contact with bodily fluids, took hold in those countries because of factors that are rare in developed countries. Because of a shortage of hospital beds, many patients were turned away from treatment centers, and family members were forced to care for them at home. The New York Times reports that, as of last week, only 18 percent of Ebola patients in Liberia were being cared for in medical facilities.

Traditional customs and beliefs have also made treating the illness more difficult. In southeast Guinea this summer locals threatened health-care workers with knives because they blamed them for causing the disease. In communities where family members prepare the body for burial there’s been reluctance to turn over loved ones’ remains. Even when families are willing to modify funeral practices, there often aren’t enough trained workers to do the burial.

Vox’s Ezra Klein notes that every year the U.S. spends an average of $8,895 on health care per person, compared to just $32 in Guinea, $65 in Liberia, and $94 in Nigeria. Despite the well-documented flaws of the American heath-care system, thanks to all the labs, hospitals, equipment, and health-care workers that money provides, potential Ebola patients in the U.S. have been isolated and treated very quickly.

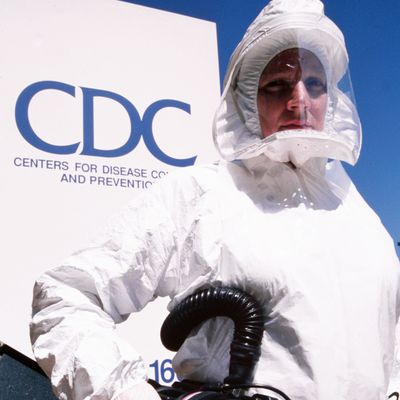

The agency has been preparing for an Ebola outbreak.

The CDC has been inundating U.S. health facilities with information about Ebola in the past few weeks. According to Politico, the agency has sent hospitals nearly two dozen documents on how to prepare, and 5,300 phones called in to a telephone briefing for hospitals held last month.

That left doctors at Texas Health Presbyterian, where the Dallas patient is in isolation, actually expecting to see an Ebola case. “If they didn’t think it was likely, they wouldn’t be doing all of that,” epidemiologist Dr. Edward Goodman told the Dallas Business Journal.

An article published in the Annals of Internal Medicine last month said some American hospitals have even been going beyond the CDC’s recommendations for treating Ebola. (For example, donning full hazmat suits, though the CDC only recommends masks, gowns, and goggles.) The authors warn this could actually be dangerous, as it increases anxiety, reduces the frequency of the patient’s exams, and could lead to health workers contaminating themselves while using unfamiliar gear.

The Dallas patient has been isolated.

There’s no proven cure for Ebola, but we know quickly isolating Ebola patients is an effective strategy, as it’s already allowed Nigeria and Senegal to contain the outbreak within their borders.

The Dallas patient has been in isolation since Sunday. After visiting family in Liberia, he flew back to the U.S. on September 20. Officials say other fliers aren’t in danger because he didn’t start developing symptoms until September 24. The three EMS workers who transported the Dallas patient to the hospital will be isolated in their homes for the next 21 days, though none have shown any symptoms.

The CDC is searching for others exposed to Ebola.

The challenge now is to find everyone the Dallas patient came into contact with and begin monitoring them as well. The “contact tracing” process is how Nigeria managed to eliminate its Ebola outbreak. After identifying one Ebola patient who arrived at the Lagos airport in July, Nigerian officials were able to find 72 people he might have infected. By tracing their contact, they found a pool of 894 people potentially infected with Ebola. Eight people died, including the first patient, but the rest have been cleared.

CDC director Thomas Frieden said that process began in the U.S. on Tuesday, and so far they’ve identified a “handful” of people the Dallas patient came into contact with, mostly family members.

CDC Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response spokesman David Daigle arrived in Dallas on Tuesday night and told CBS 11 News that ten more CDC officials were on their way. “We have senior epidemiologists — what I’d call the disease detective type — the guys that are going to go door-to-door checking on anybody who might have had contact with this patient, and seeing if it merits further attention,” said Daigle.

Even if the Dallas patient didn’t infect anyone, we’ll probably still see a few more cases in the U.S.“It was inevitable once the outbreak exploded,” Thomas Geisbert, a professor at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston, told the Washington Post. “Unless you were going to shut down airports and keep people from leaving [West Africa], it’s hard to stop somebody from getting on a plane.” As terrifying as that is, for now Americans should be more worried about the dozens of mundane ailments that might actually kill them.