How would you feel if your child married a supporter of the opposing party? I’ll admit it: I wouldn’t like it very much. Partisan affinity is not the only, or even the most important, quality in my children’s prospective future mates. I would certainly prefer a kind, well-adjusted Republican over an angry, emotionally unstable Democrat. Still, all things being equal, I’d rather not greet my child’s future spouse with a copy of Bill O’Reilly’s latest tucked under his or her arm. Does that make me a bigot?

Cass Sunstein and David Brooks seem to believe it does. Indeed, in keeping with our culture’s addiction to grievance, they have taken up a new term to express their disapproval of my preferences: “partyism.” This new term of art transforms the act of judging a person’s political beliefs into a kind of prejudice, and therefore to render it disreputable. “The destructive power of partyism,” laments Sunstein, “is extending well beyond politics into people’s behavior in daily life.” Brooks goes even further. “To judge human beings on political labels is to deny and ignore what is most important about them,” he argues. “It is to profoundly devalue them. That is the core sin of prejudice, whether it is racism or partyism.”

Brooks and Sunstein (who published his column a month ago) both cite the same two pieces of social-science research. The first is a study by Shanto Iyengar and Sean J. Westwood that found that respondents to various psychological tests display deep, implicit distrust for members of the opposing party. The second is a 2010 poll finding that 49 percent of Republicans, and 33 percent of Democrats would feel “displeased” if their child married a supporter of the opposite party, up from 5 percent and 4 percent in 1960.

It is certainly true that partyism — or “partisanship,” as we used to call it in the old days — can drive the human brain into all manner of prejudicial thinking. There is too much name-calling, knee-jerking side-taking, hypocrisy, and mindless tribalism in politics. We should all endeavor to be dispassionate and fair. It’s only fair to try to understand Republicans’ thinking, engage with their arguments on their own terms, and concede when they have a fair point. I know Republicans, and some of them are lovely human beings. That doesn’t mean I want one of them to move in next door and marry my daughter.

Note that the wording of the poll asks if you’d feel “displeased” about your child marrying an opposing party loyalist, not whether such a thing would be Montagues-and-Capulets unacceptable. I consider Republicanism a negative factor in a potential in-law. That is not the only ideological objection. I would likewise bring healthy skepticism to a Marxist, anarchist, radical Islamist, monarchist, or advocate of Greater Russia. That goes for advocates of belligerent, hypernationalism of any kind — though, come to think of it, most belligerent hypernationalists you run into in this country happen to be Republicans.

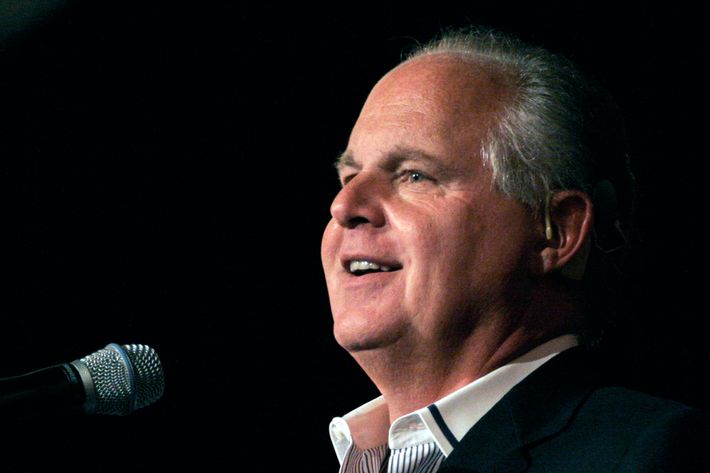

It is likewise the case that the degree of political difference would matter, too. I would be more skeptical of my child bringing home a George W. Bush Republican than a Jeb Bush Republican. A David Brooks Republican as an in-law would be less offensive, but would bring special irritants of its own. The young suitor would politely and reasonably opine that it would be nice if only both parties could propose to replace sequestration with a mix of higher taxes and lower retirement spending, or to advocate higher public investment to take advantage of low interest rates, and I’d be stalking away from the dinner table to produce proof that the Democrats had done the exact thing he castigated them for failing to do. That, in turn, would be less pleasant than listening to your son- or daughter-in-law quote Rush Limbaugh or explain why Russia is merely exercising its self-defense in Ukraine.

It’s okay to judge people’s political values. It’s not like the sports team you root for or even (exactly) like a religion, where you are mostly born into your loyalty. Politics expresses moral values.

That is precisely the attitude that troubles Brooks, who complains that “political life is being hyper-moralized.” If you want to argue that partisanship is ruining American society via hypermoralization, consider some of the ways American political life has changed since the 1960s. It is true that, 50 years ago, hardly anybody objected to their child marrying outside their party. That is because the parties lacked ideological cohesion. The 1960s were when my liberal Democratic mother met and married my liberal Republican father. Their opposing voting habits did not create problems because they disagreed very little about policy. They’re both liberal Democrats now.

American politics may have been much less partisan in the 1960s, but it was not lacking in hypermoralization. Indeed, it was far more violent. You had white supremacists murdering civil-rights activists in Mississippi, police brutalizing protestors in Chicago, and construction workers beating up hippies in New York City. That angry, hypermoralized politics took place outside of, or within, parties rather than between them.

There are millions of Americans who think it’s okay to deny legal citizens their voting rights or force them to go without health insurance. Those people live in a different moral universe than I do. They’re not necessarily bad people. (Lord knows the people who agree with me on those things are not all good.) But, yes, I believe their political views reflect something unflattering about their character.