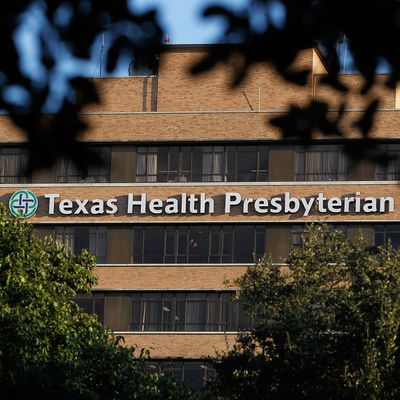

The Texas Ebola patient, a Liberian national named Thomas Eric Duncan, was admitted to Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas on Sunday night, where he has since been kept in isolation. At a press conference this afternoon, hospital and public health officials explained that Duncan had first sought care in the hospital’s emergency room a few days earlier, late on Thursday night, though his symptoms had not been very specific then. During that first visit, an emergency nurse asked him whether he had traveled anywhere recently, a question meant to screen for Ebola exposure, and Duncan replied that he had just come from Liberia. “Regretfully that information was not fully communicated” to the rest of the medical team, the hospital chief executive said today, and Duncan was sent home, with a diagnosis of a “low-grade fever from a viral infection.” By the end of the weekend, he was back.

You have to feel for that nurse, and that medical team. Dallas officials are now monitoring five children for Ebola exposure who “possibly had contact with [Duncan] over the weekend.” If the nurse had successfully communicated the news about Duncan’s recent trip from Liberia to the rest of the medical team, he surely would have been in the hospital through the weekend, not at home near those children or anyone else.

But these details also explain exactly how much pressure medical and public health systems can come under when they are up against a lethal communicative disease like Ebola, and how such mundane errors — a nurse failing to explain a detail clearly to a doctor when both are rushed, or the doctor’s failure to understand — can allow the contagion to spread.

It is beginning to seem as if modern supportive care, of the kind Western hospitals can offer, may be sufficient to keep patients with the Ebola virus alive, and to restore them to health. “I have no doubt that we will control this case of Ebola so that it does not spread widely in this country,” said Thomas Frieden, the director of the Center for Disease Control, and he confidently described the system in place, of isolation, monitoring, and disease detective work. (Such measures seem to have worked in Nigeria.) But the small errors at Presbyterian Hospital on Thursday show something about why despite heroic efforts, doctors and health officials in Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia have still not been able to contain the disease there — why it seems as hellish as ever. The Presbyterian Hospital episode shows, in other words, just how perfect a system of medical isolation and containment needs to be.