A cardinal fact of American politics that has emerged during the Obama years is that demographic forces are slowly and inexorably driving the electorate leftward. But the Republican Party has its own corresponding advantages. Its voters turn out for elections reliably, not just in spasms of quadrennial excitement. They are dispersed efficiently in rural and exurban House districts, and reside disproportionately in small states that have more per capita voting power in the Senate. All these things give the Republican coalition, even as it remains unable to muster a presidential majority, unassailable control of Congress.

The midterm elections did not alter this bifurcated structure. Instead, they exposed a grim reality for liberals. The Democratic presidential majority is a fragile asset, and its value as a driver of positive change is presently exhausted. In the near term of American politics, the enervating stalemate of the last four years is the best possible outcome. The next party to have a chance to impose its vision upon the federal government will very likely be the Republicans.

In the giddy wake of Obama’s 2008 election, Democrats almost immediately plotted ways to keep their army of newer, younger voters mobilized as a continuous standing force, exerting constant pressure on Congress to deliver the change they had demanded. There would be meet-ups, there would be emails, and there would be even more emails.

None of it worked. The Obama movement melted away almost immediately, withdrawing from politics even before the new president had taken office. The face of grassroots political activism during Obama’s first two years was the furious, disbelieving backlash that had emerged in the waning days of 2008. Democrats plotted tactics to bring their voters back out for the 2010 elections, but these proved a dismal failure — the midterm electorate proved to be much older and whiter than the one that had elected the president.

The Democrats have spent the last two years or more trying to avert the 2010 disaster. They built the “Bannock Street Project,” a $60 million project involving some 4,000 paid staffers. It took its name from the location of the field headquarters for Michael Bennet’s Senate campaign, the party’s sole midterm-mobilization bright spot.

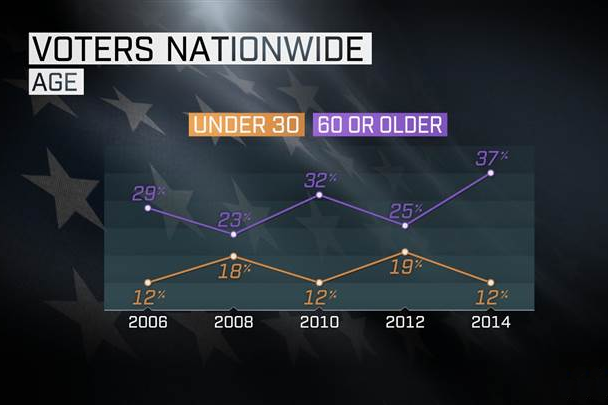

That, too, failed. Democrats again won voters under 30. (They also won voters between the ages of 30 and 44.) Those voters simply did not materialize. If anything, the 2014 electorate was even older than the 2010 version:

Liberals may still own the future of American politics, but the future is taking a very long time to arrive.

So what happens now? In the short term, nothing. The newly minted Republican leaders are mouthing the requisite platitudes about cooperation. But Mitch McConnell did not become the majority leader by cooperating. His single strategic insight is that voters do not blame Congress for gridlock, they blame the president, and therefore reward the opposition. Eternally optimistic seekers of bipartisanship have clung to the hope that owning all of Congress, not merely half, will force Republicans to “show they can govern.” This hopeful bit of conventional wisdom rests on the premise that voters are even aware that the GOP is the party controlling Congress. In fact, only about 40 percent of the public even knows which party controls which chamber of Congress, which makes the notion that the Republicans would face a backlash for a lack of success fantastical.

McConnell’s next play is perfectly clear. His interest lies in creating two more years of ugliness and gridlock. He does not want spectacular, high-profile failures that command public attention — no shutdowns, no impeachment. Instead, he wants tedious, enervating stalemate. McConnell needs to drain away any possibility of hope and excitement from government, so that the disengaged Democratic voters remain disengaged in 2016.

And 2016 is where the Senate rout will have its full effect. Both parties had assumed that Republicans would most likely gain a narrow majority in the upper chamber of 51 or 52 seats. This would have been tenuous enough that Democrats could wrest back control two years later, when the larger, presidential electorate returns, and Republicans have to defend seats in several states that elected Obama. But the Republicans now appear to hold 54 seats — enough to withstand the likely reversal. Their House majority has likewise expanded.

All the foregoing brings us to two conclusions, both of them disquieting. The first is that Democrats stand almost no visible prospect of attaining a government majority. The structural advantages undergirding Republican control of both chambers of Congress are so imposing that only extraordinary circumstances could overwhelm them. Democrats managed, briefly, to gain control of Congress when the catastrophe of the Bush presidency created two successive national wave elections in their favor.

Only that sort of freakish event would suffice. And Democrats might notice that, since winning back Congress requires a backlash against the president, their “positive” scenario requires first surrendering to Republicans’ total control of government. As long as Democrats hold the White House, Republican control of Congress is probably safe — at least for several election cycles to come.

The second conclusion is simpler, and more bracing: Hillary Clinton is the only thing standing between a Republican Party even more radical than George W. Bush’s version and unfettered control of American government.