Erik Finman’s parents Paul and Lorna, met at Stanford University in the 1980s, when Paul was getting his Ph.D. in electrical engineering and Lorna was getting hers in physics. Their first date consisted of sitting in her room eating a can of beans. “Our dad is, like, the least romantic person ever,” says Erik, 16. “She had a spectroanalyzer that he wanted.” Paul and Lorna married and eventually moved with their three young sons to Post Falls, Idaho, near where Paul had grown up, and since 9/11, their company, LCF, has prospered, winning lucrative contracts from the Department of Defense to make specialized amplifiers with the ability, among other things, to jam the improvised explosive devices American troops encountered in Iraq.

On the outskirts of Coeur d’Alene, Post Falls is populated largely by the rural poor, but the very rich have also been drawn to its remote beauty. It’s a place where you might hear gunshots over breakfast and also where the Finman family’s friends include Burt Rutan, the Virgin Galactic aerospace engineer. The Finmans, who don’t think much of the local education system, home-schooled their older boys, giving each an office at LCF to pursue his interests. “Instead of recess,” their son Ross, 25, says, “we’d get time with an engineer.” Scott, now 28, who was into coding, entered Johns Hopkins University when he was 16. Ross, who as a kid played with Legos until his fingers bled and scarred, became interested in robotics, did his senior year in high school at Harvard when he was 16, and is now pursuing his Ph.D. in artificial intelligence at MIT.

Erik, the youngest, took longer to find his path. Eager for his mother’s approval, and more sensitive to her judgments than his brothers, he bristled at homeschooling. After first grade, his parents put him into a series of private and public schools, but none took. Erik was left disengaged and unhappy. A teacher told him he should drop out and work at McDonald’s.

But it had always been clear to the family that he was bright and curious and creative. When he was a toddler and the Finmans were living in a motel — this was pre-9/11, and their company was struggling — he had wandered into the electrical room and started flicking switches, erasing the reservations system. One year, he crept into his mother’s bedroom, swabbed her mouth with a Q-tip without waking her, then used the saliva sample to commission a painting of her DNA with which to surprise her at Christmas. And though he was the only brother not to get his ham-radio license, he did develop an extreme fascination with popular technology, endlessly scouring tech blogs like the Verge, watching every Steve Jobs keynote speech, and perseverating about gadgets to weary family members. “He’d be OCD about their functionality and usability,” Ross says. If Erik identified a product flaw, “it legitimately bothered him. He’d be in a bad mood for a couple of days.” Ross’s Christmas gift to Erik one year was a mini Steve Jobs outfit of jeans and a black turtleneck.

The Finman brothers are close and also extremely competitive with each other. When Scott, in early 2013, told Erik about the digital currency bitcoin, and said he’d bought 50 of them, Erik decided to spend the $1,000 he’d just received from his grandmother to buy a hundred. A year later, Ross gave him a book, Without Their Permission, by Reddit co-founder Alexis Ohanian. In Erik’s whole life, prior to this, he had read only a single book voluntarily (Walter Isaacson’s Steve Jobs biography), but he devoured Ohanian’s book, which articulates the power of the internet to let anyone — like, say, a 15-year-old mediocre student in rural Idaho — become an entrepreneur. Erik was desperate to meet Ohanian, who, as it happened, was raffling “office hours” for charity. For $8,500, Ohanian promised waffles and a Brooklyn Nets game. Erik asked if his parents would pay the fee for him, but they felt it was too much money and that Ohanian was a fad. So they said no. Erik was undeterred. When he read that the price of a bitcoin had soared to $1,200, he decided to sell his for $100,000, and got his evening with Ohanian. “The whole time I had to check myself and remind myself I was talking to a teenager,” Ohanian says. “He’s a very driven young man, far more driven than when I was at his age.”

Around the same time, Erik found a freelance programmer on Elance and paid him to make a Flappy Bird knockoff; a week later, it was for sale in the Android app store. It wasn’t a moneymaker, but it was an eye-opening experience, real-life proof of Ohanian’s concept. And Erik already had a bigger venture in mind. His disappointing educational experiences had convinced him of the need for a marketplace for video-chat tutoring, where teacher-hungry students in remote places could connect with a far-flung network of student-hungry experts. Plugging a recent homework topic (geometric angles) and a hobby (robotics) into an online word-masher-upper yielded a company name — Botangle — and Erik went to a nearby Starbucks with a sign offering to buy a cup of coffee for anyone who’d listen to his idea and tell him what they thought of it. Some 20 people gave him feedback.

Encouraged, Erik started hiring designers and programmers all over the world, and he soon had a website up and running. He was consumed with what he was doing, and it was proving to be much more educational for him than school had been. Managing programmers made him want to learn to code; having to do taxes made him want to learn about accounting. His mother and older brother suggested he drop out and work on the business full time. Evaluating Erik using traditional academic metrics, Ross says, is “like judging fish by their ability to climb a tree.” When Erik announced that he didn’t want to go to college, his dad agreed on the condition that he make $1 million by the time he turned 18.

Even by the standards of Silicon Valley, Erik Finman is short in the tooth. Venture capitalists, the chief purveyors of the tech whippersnapper as archetype, have tended to focus on mere young adults: “People under 35 are the people who make change happen” (Vinod Khosla) … “The cutoff in investors’ heads is 32” (Paul Graham) … “They don’t have distractions like families and children and other things that get in the way” (Michael Moritz). Mark Zuckerberg, whose personal contribution to glib ageism was “Young people are just smarter,” was already 23 when he became a billionaire. But the lower the number, the better, it seems, independent of what accomplishments may yet attach to it, and when Erik hosted an Ask Me Anything on Reddit (“I’m 15 and I Have 20 People Working for Me All Around the World for a Company Called Botangle”), it drew scores of comments. Erik found himself trending on Twitter, and he ran with it.

The Reddit AMA led to a write-up on Mashable and an invitation to the Thiel Summit, which led to a summer internship in Palo Alto with the start-up Sprayable Energy (“Like Red Bull for your skin,” Erik explains). While there, Erik had an idea for another business. Based on his gathering conviction that the best way to learn is by doing, he and a fellow intern decided to hold an event, Intern for a Day, that would improve upon traditional résumé-plus-interview recruitment. Companies and would-be interns would meet for a fast round of vocational speed-dating. Employers would then pick a handful of kids to spend the rest of the day working on an actual project they needed help on, assessing them for possible internships. Aspiring interns, for their part, would get a chance to sample a company and line of work while also auditioning for something more full time.

StartX, the Stanford accelerator where Sprayable Energy was based, said Erik and his partner could use their space for the event, and Sprayable Energy itself was one of the companies that would participate. Aiming for a hundred applicants, Erik was inundated by several hundred, and before the event had even taken place, he was trial-ballooning eight more, advertising intern-matching events in other cities and seeing similarly enthusiastic responses. With an unexpected hit on his hands and with Botangle not having gained much traction, he quickly did the classic Silicon Valley “pivot,” moving his focus to Intern for a Day. “It already has a lot more users with a lot less work,” Erik says. He decided to stay in Palo Alto.

Being a 15-year-old entrepreneur living on his own posed certain challenges. Erik had incorporated his company in his mother’s name; now she also had to rent an apartment for him. When he flies, she has to sign a waiver, and until recently exit-row seats were off-limits to him. Expedia requires users to be 18 to book travel, so Erik transferred his loyalties to the Ohanian-affiliated Hipmunk. Though he recently got his learner’s driving permit, he still relies on Lyft and Uber to get around the Valley. Certain grants he’d like to apply for have minimum-age restrictions. All of which gave the dewy-eyed entrepreneur yet another idea. “Eventually, as a side project, I’d like to build an apartment complex for people under 18 and do flight bookings for people under 18.” But, he acknowledged, “I don’t think there’s a lot of money involved; there are probably only 20 people in 8 billion in the world” who face his particular set of problems.

Though his parents are obviously more relaxed than most, they’re still protective: When Erik moved to Palo Alto, his mother installed tracking software on his iPhone, and when Erik had his dinner with Ohanian at Junior’s, near Barclays Center, she hovered anxiously at the Applebee’s across Flatbush Avenue.

Socializing for Erik is a predicament. “One thing about being 15 in the Bay Area,” he says, “I hang out with a lot of 20-year-olds. The Bay Area has the lowest amount of high schools per population, I think.” When his older friends go to parties that double as networking events, Erik must glumly part ways at the door, barred as underage. He has found it hard to meet someone his age he can have an intellectual conversation with. He has profiles on sites like OkCupid and Tinder where he’s listed as 18. “There’s this 16-year-old girl who invented a flashlight powered by body heat. She was on The Tonight Show. I was jelly,” he says, envy creeping into his voice. “I sent her a Facebook message but accidentally sent her a giant cat sticker.” She never responded. His hometown friend Keely Brennan, who accompanied Erik on his Ohanian outing, says Erik is underplaying his newfound appeal to girls. “We were in a store in New York talking. I said, ‘How’s your love life, my man?’ He said, ‘Well, you know, I’ve got this girl and this girl and this girl.’ He’s like, ‘I noticed that the farther I get away from home, the more girls like me.’”

His age, whatever its drawbacks, has clearly been an invaluable calling card. While at Sprayable Energy, he and a fellow intern approached Paul Graham, the venture capitalist, at the Palo Alto breakfast spot Joanie’s Café, where Erik says he got flustered and became uncharacteristically inarticulate; nonetheless, Graham recognizes him now, calling him “breakfast guy.” Erik applied to the start-up incubator Y Combinator this fall and also for a Thiel Fellowship. He started auditing 29-year-old Y Combinator president Sam Altman’s class at Stanford. And he gets invited to events like TEDxTeen. A few months ago, Erik sent a bunch of links about himself to the teacher in Idaho who’d told him to work at McDonald’s. Subject header: “Look at me now, bitch!”

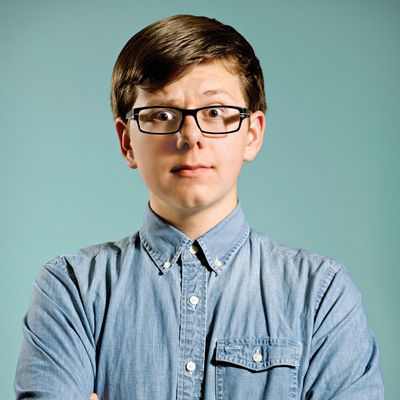

In pictures, Erik can look small and chipmunk-cheeked, a baby-faced nerd, but he is nearly six feet tall and lean, thanks most recently to the Paleo diet. His hair is thick and mussed (“I have a man crush on Andrew Garfield”) owing to his No Poo regimen (he hasn’t washed it in a year), which he learned about on Reddit. He wears a steel Pebble smartwatch. Far from being an awkward code jockey, he is wry and outgoing. He boasts about the “two-pack” he briefly had.

In early October, Erik flew to London for TEDxTeen. He was enjoying more freedom than he has in Palo Alto — though he’d brought three phones with him, “the tracking software doesn’t work in England, fortunately.” Still, because he is a minor, the conference had paid for his brother Ross to come along as his guardian. The three of us had breakfast at a greasy spoon near their hotel in the Docklands.

Erik’s relationship with Ross is complicated. When Erik was 7 and Ross 16, there was a three-month period when Ross single-handedly took care of his little brother (their parents were away for work), and besides sharing a fraternal closeness, they are both aware of a secondary, sometimes jousting father-son dynamic. Earlier, in their hotel, Erik had described Ross as “the second-best-looking guy in the family,” and as Erik drank his tea (he doesn’t drink coffee or alcohol: “We’re basically nonreligious Mormons”), and Ross had a full English breakfast, the rivalry was overt. “I got a news article when I was 8,” Ross pointed out. “Yeah, yeah,” Erik said. Ross continued: “Now Erik has to show me up, and I’ll be working for him one day.” He paused, then added: “Over my dead body.” Erik and Ross debated whether Scott was 16 or 17 when he went to Johns Hopkins. “I’m the only one in my family without a legitimate company,” Ross said, though it turns out he does have a start-up built around a device Erik described as “like SodaStream for food.”

That afternoon, after receiving a legally mandated “safety briefing” on child-labor rules, inappropriate touching, and the like, Erik stood at the back of a theater in the O2 arena in London, waiting to rehearse his talk, which he was calling “Be Something for a Day.” Inspired by Intern for a Day, Erik had broadened the concept, in his own life, to a more general “for a day” philosophy, wherein he tries to learn something new every day. He’d visited a Buddhist temple in New York. He’d auditioned for X Factor in Spokane. He’d spent a day trying to master the cooking of macaroni and cheese. His talk in London was going to tell his own story and extol this approach to life.

If there is a debutante ball for tech prodigies, TEDxTeen is it. Erik’s fellow speakers included a 14-year-old inventor of anti-cyber-bullying software and an 18-year-old who for several years had been advising multinational corporations on supply-chain logistics. Fewer than half the speakers were still teenagers, but all had either accomplished something at that age or done something the organizers felt would be inspiring to teens. TEDxTeen filters the glibness of TED proper through the theatricality of adolescence (past speakers have included a teen who “invented a cancer-detection test out of paper” and another who “created a radio station out of garbage”). Erik’s talk promised to be more down-to-earth, but with one day to go before he took the stage, he was anxious about whether it struck quite the right balance. In recent weeks, he’d gone to a couple of Toastmasters meetings to improve his public speaking, watched hours of Ohanian videos, and studied the TED talk Guy Pearce delivers in Prometheus. He felt that his own talk’s inspiration-to-funny ratio, which he pegged at 20-80, needed to be more balanced.

Onstage, right then, a British kid named James Anderson was touting Space Lounges, his “revolutionary digital retail experience” that in some hard-to-grasp way involves merging digital and physical shopping. “He got funding from Richard Branson,” Erik said quietly. Next up was Gabi Holzwarth, who’d started out as a street violinist in Palo Alto and become the private-concert darling of the Valley (as well as the girlfriend of Uber founder Travis Kalanick). Besides being a poised and demonstrative stage performer, she had a powerful story to tell about her struggle with eating disorders, and she held the room rapt.

“That’s the talk to beat,” Erik said when Holzwarth had finished. “Hers was 99 percent inspiration. She cracked one joke.” (She didn’t, actually.) “About anorexia,” Erik said dryly. Ross shook his head and said, “You’re going to burn in hell.” Erik was “jelly,” he said in his own defense. “Maybe I need to add some emotion to my talk. Should I talk about my problems in school?” Ross pushed him to go talk to Holzwarth, and he did. She invited him to a party that night that Google’s Eric Schmidt was throwing at the Shard, a spiky skyscraper. Erik said he wouldn’t attend “on principle,” because he viewed Schmidt as the chief underminer of Google’s onetime “Don’t Be Evil” idealism.

As Erik’s turn to do a run-through approached, the state of his nerves fluctuated. “I’m going up and down in confidence,” he said, “like, I’m going to kill it” — he held a hand high — “No, I’m going to fail” — and swung his hand low. Ross’s judgment meant a lot, and his presence made Erik’s anxiety surge. They’d already agreed that Ross would leave the room during Erik’s talk tomorrow, but now Erik briefly considered asking Ross to leave even for this rehearsal. Ross stayed, Erik went onstage, and it didn’t go well. He kept freezing up and apologizing. The event’s two speaking coaches, in the front row, repeatedly told him, “Don’t say you’re sorry.” He barely made it to the end. Afterward, he was upset, and he disappeared to call his mom, who gave him a pep talk, reminding him that he and Ross have different learning styles. “He’s either going to be a billionaire,” Ross told me, “or he’s going to crash and burn epically. Those are the two options.”

“Ross and I get into scuffles,” Erik explained later. He asked Ross to skip not just the next day’s talk but the entire event and hugged him in apology. “It’s always my fault,” Ross said. “Sorry,” Erik replied. He had asked for a do-over of his rehearsal, and a few hours later, when he did it without Ross in the room, it went much more smoothly. Afterward, when one of the speaking coaches saw Ross outside, he told him: “Don’t come tomorrow.”

That night, Erik stayed up late, preparing and psyching himself up by watching “a ton” of Ohanian videos again. He’d been reassured to see that Ohanian hadn’t always been a polished speaker — his later talks were much better than the earlier ones. And he reminded himself that before coming to London, when he’d given a talk at a high school in Boise, it had gone great. There, in a place where people had once made fun of him, he’d been treated like a star. His laptop, with all his notes, had died, and he’d winged it, and he still got a standing ovation. “Winging it is my education,” Erik said.

The next morning, Ross left before dawn; since he couldn’t attend his brother’s talk, he’d decided to Chunnel to Paris. In the hotel lobby, Erik commiserated with another speaker: “At least we’re not going after the anorexic girl.” Arriving back at the O2 arena, Erik received his name tag, which read, as he’d requested: WHITE KANYE WEST. He and the other speakers huddled onstage and did relaxation exercises. The musician and producer Nile Rodgers, whose We Are Family foundation puts on the conference, led them in a breathing routine.

In the greenroom, the speakers idly chatted, and Erik suggested to a 14-year-old that she should drop out of school. “Someone’s going to be paying a quarter of a million dollars,” he cautioned when she said she intended to go to college. When a speaker revealed that she was 24, someone quickly said, “So you’re officially old.” Erik’s speaking time approached. “I’m getting nervous,” he said. “I’m gonna wing the ending.” It was time for his session to start. The emcee exhorted the audience of young people to dance to the Auto-Tuned strains of Daft Punk’s “Around the World.” Erik, miked in the front row, shimmied exuberantly. When his moment came, he ascended to the stage and spoke without notes. He didn’t choke. His talk went over well, the audience laughing especially loudly at the rock-hard-abs joke he told while showing a slide of Rodin’s Thinker to illustrate his brow-knitting struggles in school.

After the event came to an end, with a call for attendees to “go out and disrupt,” fans surrounded Erik. A 14-year-old fretted about the challenges facing young entrepreneurs, like the red tape for minors. “Forget the legality,” Erik reassured him. Kids asked for his autograph and for selfies. He high-fived them as a way of saying good-bye, something he’d learned from watching Ohanian. At a party upstairs afterward, while adults toasted with Champagne, Eric drank ice water.

The next day, Erik would fly to Boston and then on to San Francisco, where he would soon decide to give up his apartment — “It smells weird” — and live nomadically, moving from city to city as he puts on Intern for a Day events. Ohanian, who has become a mentor to Erik, has cautioned him to pace himself. “I’ll take him to Shake Shack,” Ohanian says. “I want to give him start-up advice, but I also stress: Don’t forget to have a childhood, too. Clearly he’s going to go places, but it’s also important not to squander this amazing moment of youth, and not be solely focused on work.”

A milestone loomed. On October 26, Erik would turn 16. “I’m starting to count the days,” he said. “I feel old.” Normally, his family made a big deal of his birthdays, but, his mother told me, “he doesn’t want to get to 16. He wants me to ignore it. Of course, I won’t.” As it turned out, when the day arrived, Erik was in Palo Alto. He spent his birthday judging a hackathon at Y Combinator, doing a podcast, and going out for dinner at Chipotle with another TEDxTeen speaker. Nothing special. “I had two Chipotles instead of one,” Erik said the next day. “I feel ancient. I guess the older you get, you have to stand on your own accomplishments. I feel I haven’t done enough. At 16, it feels less impressive. It makes me motivated to do more and more.”

*This article appears in the December 1, 2014 issue of New York Magazine.