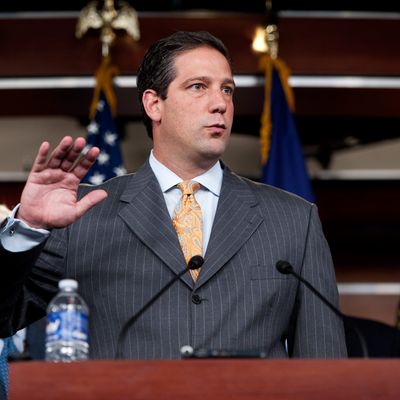

“It really is disgusting, if you think about it,” Tim Ryan is saying. The six-foot-four, Italian-Irish Congressman from Ohio is sitting in his office. Behind him is a blown-up photograph of his baby in a “Tiny Democrat” onesie. He’s inviting me to come to a hot-yoga class he regularly attends with his staff, but he’s careful not to oversell it. “People are sweating everywhere. Dudes are in there with their shirts off. If you’re like a petite, clean woman, next to this beast who’s sweating like … ” He makes a face. “Anyway, you’re invited. We’d love to have you.”

Almost everyone comes to Capitol Hill to espouse a set of ideas; usually, those ideas fit neatly in the ideological confines of a political party. Ryan’s are a bit different. He’s established himself as Congress’s mindful member, penning books on the power of meditation and what he calls “the real food revolution,” advocating for yoga, meditation, and unplugging from the internet as a salve to the stresses of modern existence. Think Deepak Chopra meets Michael Pollan, in the body of a former high-school football player turned Democratic Congressman from the Rust Belt. He’s introduced bills to add holistic and alternative-medicine programs for the treatment of veterans, to teach schoolchildren social and emotional skills through better self-awareness, to fund “integrated nutrition curricula” in medical schools — and that’s just in the last Congress.

In 2009, he secured funding for a program that teaches mindfulness at schools in his district; students there instruct each other to take deep breaths when they’re upset, or visit the peace corner to take a break from classroom stress. He’s also trying to introduce his quiet revolution to Capitol Hill, organizing a weekly staff meditation session when Congress is in town, which he estimates is usually attended by 20 to 40 staffers, and a members-only session in the House chapel, which is less well attended. “It’s usually me and Tony Cardenas from California,” he says, mentioning a fellow House Democrat. But Ryan is optimistic. “I’ve had a number of members say, ‘I want to come.’”

More recently, Ryan has expanded his holistic congressional practice to include food policy, writing a book this fall on how to get healthier foods on the dinner table — which is why he’s offered to take me to Safeway after votes. When he goes to vote, he gestures to his cell phone. “I’ll put this in my pocket and just walk, try to reconnect. With yoga, it’s the same thing; you take it off the mat. That’s the practice, but are you present when you’re off the mat? That really is the key.”

Twenty minutes later, he’s finished votes and taken a short drive to a Safeway on Capitol Hill. “In my family, I do the grocery shopping,” he says. “It can be almost therapeutic. My wife gets so mad — I’ll go to the grocery store, and it’ll be like two hours. She’s like, ‘What happened?’”

Ryan’s journey to becoming Congress’s crunchiest member began just after his reelection in 2008, when he attended a meditation retreat in the Catskills that ended in 36 hours of total silence. He has always been an overachiever — he was first elected to the House in 2002, at the age of 29, serves on top committees like budget and appropriations, and is seen as one of the bright, young Democrats that will make up the next generation of House leaders. But after six years in Congress, he could feel himself beginning to get burned out. “Lawmakers are so anxious and they need to raise money and there’s all these elections and 24-hour news cycles and Tweeting and blogging and a crisis of every hour,” he says. “There’s no time to contemplate or evaluate and look at what’s happening and why.”

He realized that meditation had an effect on him and in so many segments of society, and it was completely free. “I just made the decision that I don’t care what people think. I believed in this; I saw the science. I met the people it was helping. I knew it helped me,” he says. “And I went for it.” So he wrote a book, A Mindful Nation: How a Simple Practice Can Help Us Reduce Stress, Improve Performance, and Recapture the American Spirit, which details how mindfulness can be used in schools, in the health-care system, and with veterans.

Ryan was deep into his mindfulness work, when an unexpected life event helped expand his holistic interests to include food. Just as Ryan and his wife were considering having their third child, his wife came down with a mysterious illness, which her doctor explained was likely caused by a childhood diet of antibiotics and processed foods that had ruined the good bacteria in her gut. The experience turned Ryan into a healthy-food crusader. “This one’s pretty good,” he says, considering a jar of peanut butter. “Not bad, three grams of sugar.”

As much as he loves it, the grocery store is also filled with perils — that’s one of the takeaways from his second book, which he released in October, The Real Food Revolution: Healthy Eating, Green Groceries, and the Return of the American Family Farm. The book, blurbed by Nestlé, Bill Clinton, and Arianna Huffington, touches on the big picture, like the farm bill’s favoritism toward large agricultural corporations and subsidies for food items that make us fat, as well as the small, like the steps individual people can take to change the way they eat.

He winds his way through the aisles, pausing to scan the sugar content on a box of Fruit Loops, peering over a meat cooler to consider various packages of pale chicken breasts wrapped tightly in cellophane, their meat juices pooling in the corner of their Styrofoam trays. “This has no hormones or steroids, which is good, but it doesn’t say anything about antibiotics,” he says, moving on. He grabs a few packages of turkey sausage to keep in the fridge of his Capitol Hill office for breakfasts on the go. Then, one of his aides, who’s coming along to do his own shopping, hands him something that really gets him worked up: a Lunchables package.

Ryan takes the package. “Did you ever read Salt Sugar Fat?” he asks, referring to New York Times reporter Michael Moss’s 2013 book about how food companies got Americans addicted to fatty, processed foods. “He goes through the evolution of the Lunchable, how it started, and then stopped selling, so they added the Oreo and they kept building.” He is speaking at a rapid clip. “Okay, so 34 grams of sugar in this thing. That’s seven or eight teaspoons — over eight. You’re giving your kid over eight teaspoons, just in this!” He waves the package around, which looks even smaller in his large hands. “And if you’re having the Fruit Loops for breakfast, you probably have one and a half to two cups. So now you’re at six, plus the milk, plus more if you have an orange juice. Then this for lunch. Do that for seven or eight years and you’ll be diabetic!” And yet, he says, it’s hard to see all of that when you’re a busy parent trying to work and put your kids through school and make sure they eat — especially when money’s tight and the crappy food is cheap.

Ryan and his wife have three kids, Mason, Bella, and Brady. For the older two, he and his wife pack healthy lunches: hard-boiled eggs, baba ghanoush or hummus with veggies, soup in Thermoses, and occasionally some slices of turkey, rolled without no bread. The kids haven’t totally gotten with Dad’s program yet, though. “My young son didn’t get the memo on my meditation practice. He’s 7 months old; I’m just starting to get back into a daily routine,” Ryan says. “Brady threw up on my books.” Ryan seemed pretty Zen about it. “Okay, we’ll text you about yoga,” he says, stepping forward to embrace me in a bro hug. “We’ll definitely do yoga!”