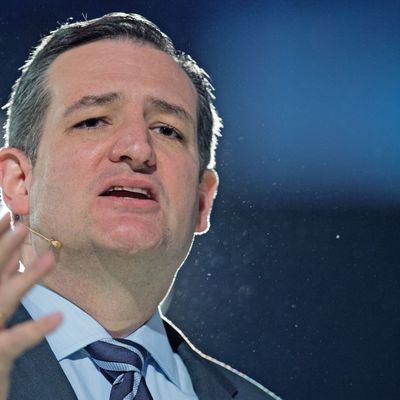

In the course of a short political career, Ted Cruz, who today announced his campaign for the presidency, has defined himself in singular terms as the authentic representation of the right. He is loathed by nearly all Democrats and many Republicans, and treated by the Washington Establishment with unusually undisguised contempt, a man apart from the crowd. And yet there is very little in his platform to distinguish him from the rest of the party. In his announcement speech, Cruz ticked through his plans for America: repealing Obamacare, a flat tax, securing the border, banning abortion, preserving traditional marriage, opposing Common Core, and unyielding support for Israel and opposition to terrorism. Cruz’s style is uniquely terrifying to his critics (or thrilling to his supporters), but the substance is unremarkable standard-issue Republicanism.

If policy does not explain Cruz’s uniquely radical image, what does? A few quotes explain the essence of Cruz’s political identity.

1. The Republican pollster Kellyanne Conway: “It’s not necessary for him to show that he’s the most conservative, but that he’s the most courageous conservative.”

2. Mike Needham, head of the conservative lobby Heritage Action for America: “Ted is exactly where most Republican voters are,” said Needham. “Most people go to Washington and get co-opted. And Ted clearly is somebody that hasn’t been.”

3. Cruz himself: “Every candidate is going to come in front of you and say I’m the most conservative guy who ever lived,” Cruz said. “Well gosh darnit, talk is cheap. One of the most important roles men and women of Iowa will play is to say, ‘Don’t talk, show me.’”

All of these passages tell us the same thing. Cruz is not attempting to distinguish himself from his party substantively. He is attempting to distinguish himself characterologically. Cruz depicts a party Establishment too cowardly to actually fight for the conservative agenda.

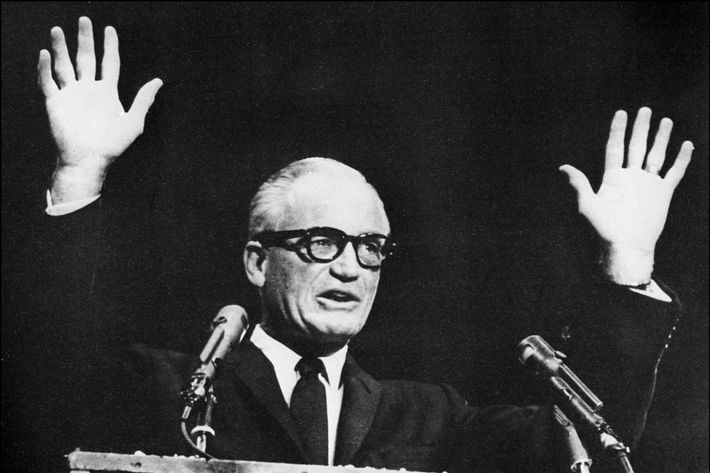

This is not only an old idea in conservative politics — it is the foundational idea of the conservative movement. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Republican Party had largely made its peace with the new role of government created by the New Deal. Conservatives were merely one faction within the GOP, frustrated by their powerlessness to influence its agenda. The conservative movement, which was identified intellectually with National Review and politically with Barry Goldwater, wanted their party to launch a full-throated counterattack on big government. They had an ideological program that differed sharply from the reigning ideology of Eisenhower and Nixon: a straightforward attack on big government as socialism.

Their substantive policies were complemented by a unique political analysis. The conservative believes that — in contrast to Republican leaders who cautioned that moderation was required in order to compete for mainstream votes — moving to the right in this way offered the party its greatest chance to win a national majority. So why hadn’t the party seized its clear path to victory? Conservatives believed they had been thwarted by feckless or even traitorous leaders. Conservative activists identified as their primary enemy the eastern Establishment, led by the hated Nelson Rockefeller, who supported what Goldwater dismissed as a “dimestore New Deal” — a pathetic capitulation to big government. “A Choice Not an Echo,” Phyllis Schlafly’s wildly successful campaign tract on Goldwater’s behalf, charged, “In each of their losing presidential years, a small group of secret kingmakers, using hidden persuaders and psychological warfare techniques, manipulated the Republican National Convention to nominate candidates who would sidestep or suppress the key issues.”

When Schlafly wrote this, the conservative movement was in a state of open mutiny against the Republican Party leadership. In the years since, conservatives have slowly won control of the party apparatus. There is no longer any serious intellectual resistance to conservatism among Republicans. Everybody within the party accepts its fundamental precepts (markets good, government bad), reveres the teachings of Ronald Reagan (himself a key force in the Goldwater movement), and draws ideological support from institutions aligned with conservatism.

Conservatives have not completely worked out how far they would go if given absolute power — back to 1932? 1905? — but they agree on the direction. This is the key factor distinguishing Cruz’s revolt against the party elite from Goldwater’s. Goldwater had both a substantive program and a political theory that distinguished him from his party’s leaders. Cruz has only a political theory. Because he agrees with the policy goals of figures like Paul Ryan and Mitch McConnell, all he can do to distinguish himself from them is stoke the suspicions of the base that those goals have been undermined from within. His shutdowns, his filibusters, his wild personal attacks — they all reinforce Cruz’s story. He is the one Republican too brave and pure to submit to the Obama agenda. If his tactics fall short, it merely serves to dramatize his colleague’s fecklessness.

All this is why so many Republicans despise Cruz, and it will make it difficult for him to win the nomination. But the loathing between Cruz and his party is not some failing of etiquette. It is his entire plan.