How Is It Possible That the Inane Institution of the Anchorman Has Endured for More Than 60 Years?

The Great American News Anchor is no different from the Great and Powerful Oz.<br /><br />

the inane institution

of the anchorman

has endured for more

than 60 years?

Some two months into Brian Williams’s six-month banishment from NBC for making stuff up, it’s not known whether he will ever return to the anchor chair at Nightly News. It’s also not known whether anyone cares. The understudy who stepped in, Lester Holt, is leading in evening-news viewership as Williams did. No one is complaining that Holt’s résumé includes three years co-hosting the Westminster Dog Show but lacks those narrow Indiana Jones escapes from danger, whether in Iraq or New Orleans, that his predecessor conjured up to prove his gravitas. No one is fretting about whether Holt sullied the dignity of an anchor’s higher calling when he did a cameo on 30 Rock. No one seems to notice that Holt is continuing as anchor at NBC’s Dateline, the trashy newsmagazine whose signature feature is “To Catch a Predator.”

The interchangeable blandness of the two Nightly News anchors and the continuity of their viewership confirm the reality that lurked just beneath the moral outrage, torrential social-media ridicule, and Comcast executive-suite chaos of the Williams implosion: For all the histrionics, this incident of media blood sport was much ado about not so much. The network-news anchor as an omnipotent national authority figure is such a hollow anachronism in 21st-century America that almost nothing was at stake. NBC’s train wreck played out as corporate and celebrity farce rather than as a human or cultural tragedy because it doesn’t actually matter who puts on the bespoke suit and reads the news from behind a desk.

Yet the institution of the network anchor persists even as such perennial eulogies are written for it, even as the broadcast networks give way to the individualized narrowcasting of social networks. As Andrew Heyward, the former president of CBS News, describes the atavistic absurdity of the franchise, the very concept that an anchor could “organize the world in a coherent way,” putting the world “literally” in a box for half an hour, is now a non sequitur. But like the cockroach, the anchorman has outlasted countless changes in the ecosystem around him. And he has done so despite being a ridiculous, if ingenious, American invention since his birth.

The network anchor’s roots are not in journalism but in the native cultural tradition apotheosized by L. Frank Baum. Like the Wizard of Oz (as executive-produced by Professor Marvel), anchors have often been fronts for those pulling the strings behind the curtain: governments and sponsors, not to mention those who actually do the work of reporting the news. With their larger-than-life heads looming into our living rooms, the anchors have been brilliant at selling the conceit that a resonant voice, an avuncular temperament, a glitzy, thronelike set, and the illusion of omniscience could augment the audience’s brains, hearts, and “courage” (at one point, a Dan Rather sign-off) as it tries to navigate a treacherous world. Just don’t look behind the curtain. Many of the charges leveled against Williams for conduct unbecoming an anchorman could be made against his predecessors too.

The strain of all-American humbug baked into television anchoring from the start has often been obscured by the industry’s penchant for self-mythologizing. Even the provenance of the term anchorman itself has been retouched for public consumption. For years it was said to have first gained currency in 1952, when it turned up in a CBS press release to characterize Walter Cronkite’s role in the network’s coverage of the political conventions. Also for years, Don Hewitt, the CBS News producer who ran the newscast, and Sig Mickelson, the first CBS News president, engaged in a friendly back-and-forth as to which of them deserved credit. (Cronkite attributed the term to a third CBS News executive, Paul Levitan.) But in 2009, Mike Conway, an Indiana University journalism professor, unearthed the far more humble origins of “anchor man.” It turns out that the term’s first use on television was in 1948 at NBC to describe the permanent member of a rotating panel of celebrities on a quiz show titled Who Said That?

This footnote would seem to have no bearing on the subsequent history of television news except for the fact that Who Said That? pioneered the networks’ blurring of news and entertainment. The show was the brainchild of the producer Fred Friendly, who would soon be revered for his partnership with the patron saint of broadcast journalism, Edward R. Murrow, at CBS, where among other feats they would famously excoriate Joe McCarthy in their prime-time show, See It Now, in 1954. Friendly’s autobiography glides by Who Said That?, Conway noted, because “he wanted to be known for working with Murrow” rather than vulgar forays into infotainment. But the proto-anchorman of Who Said That?, John Cameron Swayze, didn’t share Friendly’s highfalutin sensitivities. Even as he appeared on the NBC quiz show, he was the newscaster (not yet called an “anchor”) at NBC’s evening news — The Camel News Caravan, the progenitor of Nightly News. Swayze’s double duty of more than 60 years ago is the template for Williams’s juggling of his Nightly chores with slow-jamming the news with Jimmy Fallon.

Swayze, who was selected for the nightly Camel News by its sponsor, the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, and obediently kept a lit cigarette in an ashtray on-camera, was billed as “the nightly monarch of the air.” Anticipating Cronkite’s “And that’s the way it is,” he deployed catchphrases to both kick off his 15-minute show (“Let’s hopscotch the world for headlines!”) and sign off (“Well, that’s the story, folks! This is John Cameron Swayze, and I’m glad we could get together”). He was admired for wearing a carnation and changing his tie every night. Such was his fame that Milton Bradley, the manufacturer of Candy Land, created the board game Swayze to capitalize on his celebrity as a newsman. Swayze was certainly a step up in stature from his predecessor at NBC, Paul Alley, who edited and narrated a nightly NBC Television Newsreel in a hole-in-the-wall studio at 45th Street and Ninth Avenue during the television network’s experimental postwar, pre-anchor period. Alley was most famous for the size of his expense account and his habit of showing visitors nude photos of his wife.

But Swayze was no more of a newsman than Alley. Thanks to Jeff Kisseloff’s invaluable oral history of television’s early years, The Box — based on interviews conducted more than two decades ago, when many eyewitnesses were still around — we know that Swayze did not put great store in boning up on breaking events. “He wouldn’t even see the film before the show,” recalled Arthur Lodge, the first news writer hired for The Camel News Caravan. “He was more concerned about whether his toupee was on straight. How can you be involved with the first news program and not give a shit about what goes out over the air?”

Quite easily, as it happened. Swayze remained the NBC News anchor for seven years. And, in tandem with his rival at CBS, Douglas Edwards, he codified the role. Up until then, everything had been up for grabs in television news. Early on, the hope was “to avoid having the newscaster’s face on TV,” recalled Rudy Bretz, the first employee hired by the CBS television department. “We figured that the commentator was secondary to the news itself.” Once that lofty theory was discarded, no one knew whether the man presiding onscreen (women were never considered) should be “a man of authority” or “a working journalist,” Chester Burger, an early CBS News hand, told Kisseloff. The obvious candidates — “Murrow’s Boys,” the CBS radio-news stars who came to fame in their coverage of World War II in Europe — saw television as beneath them, or “mindless,” as Murrow put it. So CBS experimented. “We tried charming young people. We tried handsome people. We tried an old man with a beard for authority at a time when people didn’t wear beards,” Henry Cassirer, the head of CBS Television News from 1945 to 1948, recalled. “We didn’t want a brilliant man” but rather someone “likable and steady” — a visitor who would be welcome in the living rooms where early adopters were tending to put their television sets. At CBS, there were at least 12 anchors between 1944 and 1948, including a New York Daily News sportswriter, before Edwards took root. (There would be only four CBS News anchors over the next 57 years.) At NBC, Swayze was prized for the photographic memory that at the time obviated the need for him to read from a script. In that era, before the invention of the teleprompter, this skill was invaluable in simulating the aura of Oz-like omniscience.

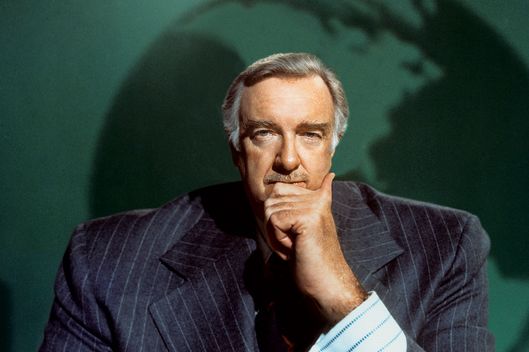

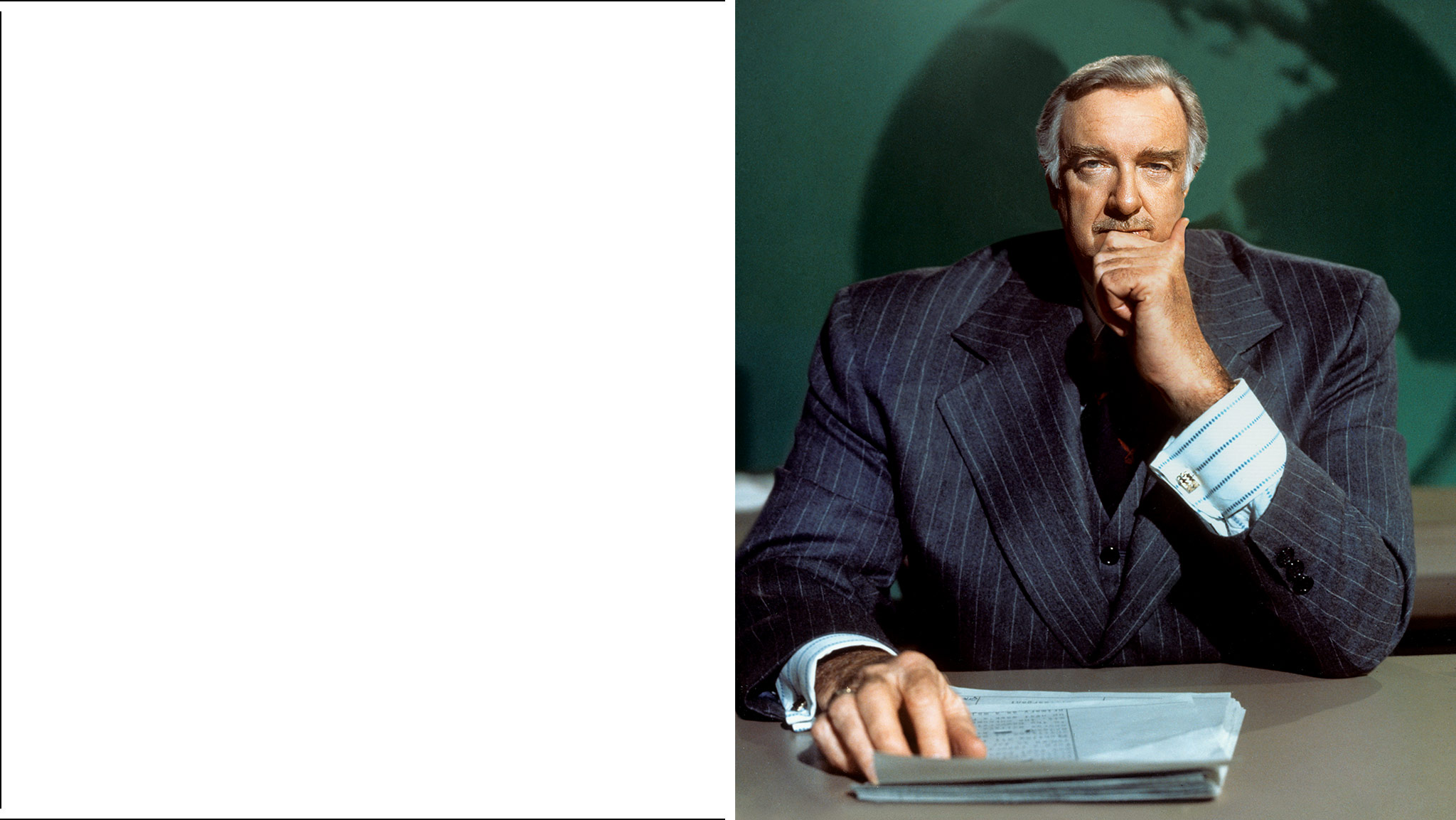

[1.]

Are We Looking at a Post-Anchor Future?

Andrew Heyward, president of CBS News from 1996 to 2005, on what will become of the evening news.How might TV news have turned out differently if the networks didn’t reward anchors more than the people who report and produce the stories? Let’s pretend for a second that the industry had evolved a different way. And let’s just say that reading the news was considered the entry-level position. That if you could read the prompter, so what? That’s how you started, but the real glory lay in finding original stories and reporting them in a compelling way from all over the world, or all over town if you were in a local station. If that were the incentive across the board, we’d be in much better shape.

By the way, there is a program like that, it’s called 60 Minutes; it only happens to be the most successful news program ever invented. So this isn’t so crazy.

Yet 60 Minutes, without a single anchor, is an outlier, while each network has its own anchor-hosted news program. If the anchor format is not as successful, how did it get to be the dominant one? The short answer to your question is, it worked.

News is sold on 25-to-54 year olds, and there’s still enough strength in that demographic that there’s plenty of profit being made, and that’s why there hasn’t been that much innovation. It’s still, to a degree, working. On the anchor side, if you were told, “You know what, we love your reporting so much you no longer have to get up at five in the morning, wait outside the courthouse on a winter’s day for the verdict to come in—you can stay in the studio, you can write your own copy if you’re in a small market or have it written for you if you’re in a big one, and we’ll pay you three to five to ten times as much,” what insane person is going to say no to that?

Now, a new generation of viewers is coming of age that, for the first time in the history of television news, is not going to emulate or step into the news habits of its parents. My kids don’t ever plan to watch a network newscast. For any reason. What’s been erosion is going to become a cliff.

Do you foresee a day when the networks abandon the anchor model? The network evening newscasts, as maligned as they are, are still bastions of serious reporting on important issues compared to most television news.

The history of innovation in American media is that the new formats don’t tend to supplant the old ones; they tend to eventually coexist. We still have radio. In this case, I think you’re going to see an evolution that doesn’t mean that the network anchor will disappear, but I do think the story and the reporter will become more important. If you look at what’s happened in print, the unit of value increasingly is the article as opposed to the newspaper. Because, chances are, the article has been shared via social media to people who don’t necessarily go to the home page of the paper, let alone buy it at a newsstand. The same thing is going to happen increasingly in TV.

What is going to come back, in my view, is the importance of sector expertise, on-scene reporting, and enterprise journalism. I saw a poster in Times Square the other day for the new season of HBO’s Vice magazine show. You know what the tagline is? “We go there.” It’s a sad day when a newsmagazine can use “we go there” as a distinctive selling point.

Once Swayze was replaced by the nightly-news team of Chet Huntley and David Brinkley in 1956, he became a pitchman for Timex watches. He ultimately was remembered more for Timex’s slogan — “It takes a licking and keeps on ticking” — than for his years as the “monarch” of news. But Swayze had helped establish an industry paradigm. John Charles Daly, who was not only the ABC News evening anchor from 1953 to 1960 but also the network’s vice-president for news, doubled as the emcee of What’s My Line?, a campy, celebrity-driven Sunday-night game show on CBS, during his entire ABC tenure. (In one season he took on Swayze’s old role of anchoring Who Said That? at NBC, too — a trifecta of network-news-and-entertainment cross-wiring.) At CBS, Murrow and Friendly traded off the high-toned See It Now with Person to Person, the higher-rated celebrity-interview show where Murrow went one-on-one with Zsa Zsa Gabor, Liberace, and Yogi Berra. Cronkite’s anchor role at the 1952 political conventions notwithstanding, he, too, was soon doubling as an entertainer on the CBS Morning Show, the network’s Today clone, where he was partnered with the puppet Charlemagne the Lion.

Cronkite ascended to the anchor chair of the CBS Evening News in 1962, succeeding Edwards. By the time he retired prematurely to make way for Rather in 1981, the identity of the network anchor as the voice-of-God arbiter of American civic virtue had been indelibly fixed in his image. Not without reason. He was a first-class reporter and an enforcer of standards, and, much to his credit, he didn’t take himself as seriously as his idolaters did. During World War II, when he worked for the wire service United Press, he covered the Battle of the Bulge and D-Day (though not, as sometimes has been erroneously written, from the front lines of Normandy’s beaches).

Cronkite is often canonized for three career highlights in his tenure as CBS anchor: welling up while delivering the bulletin of President Kennedy’s death the day of the assassination; being declared “the most trusted man in America” in a poll; and traveling to Vietnam in the wake of the Tet Offensive in 1968, at which point he declared the war unwinnable, prompting Lyndon Johnson’s announcement weeks later that he would not seek reelection. The first of these milestones was an accident: Cronkite broke the news of JFK’s death because the daytime anchor on duty, Harry Reasoner, was out getting lunch. (Reasoner anchored the coverage that night.) The second carries a huge asterisk: The 1972 poll in question, exhumed by former CBS News executive Martin Plissner in his 2000 book The Control Room, found that while Cronkite had the highest rating for trustworthiness in America (73 percent), he was the only newsman in a survey that pitted him against politicians. Even Richard Nixon clocked in at 57 percent.

The third of these iconic Cronkite moments, long regurgitated by many (myself included) as an article of faith, has it that LBJ, after watching America’s most trusted man sour on the war, turned to his press secretary, George Christian (or some other aide), and lamented, “If we’ve lost Walter Cronkite, then we’ve lost Mr. Average American.” Recounting this episode in his 1979 book The Powers That Be, David Halberstam declared that it was “the first time in American history that a war has been declared over by an anchorman.” But the writers W. Joseph Campbell and Louis Menand have since debunked this claim. There is no evidence that Johnson saw Cronkite’s broadcast that fateful night, or possibly ever, or said any such thing to anyone. The proximate motive for LBJ’s decision to abdicate the presidential race was not an anchorman’s commentary but the news that Robert Kennedy would soon challenge him in the Democratic primaries as an antiwar candidate.

American editorial and public opinion had turned against the war well before Cronkite publicly did so, in any case — much as it had already turned against Joe McCarthy by the late date that Murrow and Friendly did. (Murrow’s broadcast acknowledged the wave of anti-McCarthy opinion cresting through the nation’s editorial pages.) The truth is that network anchors, answering through the years to rapacious corporate executives like William Paley at CBS and Jack Welch at NBC, rarely led the way in aggressively challenging authority in Washington. One quasi-exception occurred in 1972, when Cronkite, four months after the Watergate break-in, vexed Paley and the Nixon White House with a two-part special focusing belated national attention on the reportage of Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward in the Washington Post. Another departure from typical network-anchor timidity, some 30 years later, was made by Peter Jennings of ABC, whose skepticism about the Iraq War put him ahead of his television-news colleagues and many print journalists as well. Neither Brian Williams (then an MSNBC nightly anchor) nor any of his network peers summoned the bravery required to question the fictional evidence for Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction. In terms of damage done, that sin of omission was far more costly than Williams’s harmless, if dopey, fictionalized self-profile in courage under enemy fire in Iraq.

Paddy Chayefsky’s satirical movie Network, with its apocalyptic portrait of a network entertainment division’s corruption of a pristine CBS-like news operation, could not have been better timed. It was released in 1976, the same year that Roone Arledge, the ABC Sports impresario who had annexed his network’s news division, lured Barbara Walters away from NBC with a million-dollar salary to serve as the first female (co-)anchor of the evening news while continuing as a celebrity interviewer. Suddenly anchors became stars of show-business magnitude, as measured by their ballooning seven-figure salaries and the flashiness of their personal publicity. The gap in compensation between the anchor and correspondents in the field soon widened so much at all three networks that anchoring was incentivized over reporting the news — a development that Cronkite, who missed the anchor-salary boom, would publicly lament in retirement. Richard Salant, the president of CBS News, spoke for received opinion when he condemned Arledge’s addition of Walters to the evening news as a “minstrel show.” But the blending of news and entertainment that ABC was pilloried for — and that Network inveighed against — was nothing new. Only the scale had been ramped up.

In retrospect, a more prescient film satire of network news appeared in 1987, with James Brooks’s Broadcast News. Brooks had briefly passed through CBS as a page and news writer at the start of his career. Later, as the co-creator of the CBS sitcom The Mary Tyler Moore Show, he helped devise the memorable local-news anchorman Ted Baxter, whose boneheaded off-camera intellect and pompous on-camera vanity anticipated every comic send-up of local anchors since. In Broadcast News, Brooks moved on to network anchors. The film’s prologue introduces an adorable blond, blue-eyed boy in Kansas City, Missouri, circa 1963, who is telling his father his report card is full of C’s and D’s. “What can you do with yourself if all you can do is look good?” the boy asks his dad. Brooks freezes the frame and throws up the legend: FUTURE NETWORK ANCHORMAN.

[2.]

I’m Useful, I Swear!

Anchors through the ages wrestle with the purpose, and practice, of their own jobs. “It’s a little like being a clergyman … Most of the week you conduct standard religious services, but the importance is when something goes wrong. Right now somebody could come to that door and say, ‘A candidate has been shot, go on the air.’ I’d walk in, draw on a lot of experience in this field, and ad-lib for five hours.”

“It’s a little like being a clergyman … Most of the week you conduct standard religious services, but the importance is when something goes wrong. Right now somebody could come to that door and say, ‘A candidate has been shot, go on the air.’ I’d walk in, draw on a lot of experience in this field, and ad-lib for five hours.”

John Chancellor, NBC Nightly News anchor, 1970–82

“The one thing I hope, and I believe, is that even my enemies think that I am authentic. In my heart, my marrow, I am a reporter. And one who doesn’t play it safe.”

Dan Rather, CBS Evening News anchor, 1981–2005

“People say I’m too aloof … in some ways, that’s a compliment. It is not my emotions that matter on a story. It is the emotions of the people we’re covering. Edward R. Murrow used to go up on the rooftops of London. Do you think his aim was to let Americans know how he was feeling? His aim was to let the American people know how the people of London survived.”

Peter Jennings, ABC World News Tonight anchor, 1983–2005

“The audience is more sophisticated than we give them credit for—they don’t want a mechanical Ted Baxter … I’m a serious, caring, compassionate person. I hope that comes out.”

“The audience is more sophisticated than we give them credit for—they don’t want a mechanical Ted Baxter … I’m a serious, caring, compassionate person. I hope that comes out.”

Katie Couric, CBS Evening News anchor, 2006–11

“I am a 43-year-old anachronism … I am the kid in front of the TV set wondering what it was like to anchor the evening news.”

Brian Williams, NBC Nightly News anchor since 2004, currently suspended

“I hope people know that when I’m sitting there, it’s not some guy on a desk on a platform with sort of this voice-of-God approach.”

David Muir, ABC World News Tonight anchor since 2014

“The anchoring … is the least important part of my day.”

Scott Pelley, CBS Evening News anchor since 2011

“I think … that it would be absolutely splendid if you got rid of the anchorperson entirely and found some other way … to do the broadcast.”

“I think … that it would be absolutely splendid if you got rid of the anchorperson entirely and found some other way … to do the broadcast.”

Walter Cronkite, CBS Evening News anchor, 1962–81, said in the penultimate year of his time behind the desk.

Cronkite and Williams were college dropouts; Jennings didn’t finish high school. The little boy in Broadcast News grows up, in the hunky form of William Hurt, to be an ambitious, if vacuous, network reporter on his way to succeeding a Cronkite-ish veteran (Jack Nicholson, devilishly enough) as evening-news anchor. Brooks contrasts Hurt’s anchor-on-the-make with an equally ambitious, hard-driving network reporter, played by Albert Brooks, who has his own anchor aspirations but is too intense and implicitly too Jewish to beat out his less-weighty Ken doll of a rival. The brains behind both these rival newsmen, and the essential voice in their on-air earpieces, belong to a producer smarter than both of them, played by Holly Hunter and modeled on Susan Zirinsky, a real-life producer still in place at CBS News.

Incredibly, in light of recent events, the plot of Broadcast News turns on an incident in which the Hurt anchor-to-be burnishes his image by falsifying his own role in a searing news segment. But the outside world never learns of his ethical transgression, and there is no network suspension. His career moves forward even as worthier news hands are laid off all around him in a brutal round of newsroom downsizing that also looks strikingly contemporary in a movie made almost three decades ago.

In casting Hurt, Brooks was putting his finger on another crucial if often unspoken component in the deification of the network-news anchor: casting for a certain look and all-American pedigree. The first network anchor to have leading-man qualities in the Hollywood manner was Huntley, who had little news experience but was a tall, handsome, and deep-voiced product of small-town Montana. Huntley was partnered with the more cerebral David Brinkley, a seasoned reporter with a wry delivery and a witty writing style, because, as Reuven Frank, the Huntley-Brinkley Report’s longtime producer, explained, Brinkley didn’t have “the authority that the audience wants” and “Huntley did.” What gave Huntley that authority, Frank said, was “that great leonine head and that Murrow-like voice.” The “image of probity or authority” was “a lie,” Frank added, but “people want to believe it.”

Cronkite, like such competitors as Brinkley and the subsequent NBC anchor John Chancellor, did not remotely resemble a movie star. (Truman Capote was so disapproving of Cronkite’s screen presence that he tried to talk his friend William Paley out of making him anchor.) By the time of Cronkite’s retirement, the network-casting clichés mocked in Broadcast News were entrenched. When I interviewed Cronkite in 2002, he said he was struck by the phenomenon he spotted at journalism schools. “I look around the crowd,” he said, “and see who wants to be an anchorperson, not a journalist. The women are all blonde, and so are the men. The few serious journalists look like they got out of bed a little late; they ask questions about the coverage. The others ask: ‘How can I get a job? How can I establish my credentials?’ ” Tom Brokaw, though fitting the anchor model himself in looks and origins (small-town South Dakota), made a point of separating himself from that stereotype when he was on the brink of becoming Nightly News anchor. “I always wanted to be a reporter,” he told the Times in 1980. “This generation just wants to be stars. They’re more familiar with a hot comb than with an idea. If there had been no TV for me, I would have gone into print. These people would go into acting.”

It was good looks that helped propel Jennings to the anchor chair at ABC at the preposterous age of 26 in 1965. He figured out that being handsome and poised was not enough to make the job satisfying. When he left after three years — guilty of being “too young, possibly too pretty, and probably too Canadian,” in the later judgment of Roone Arledge — he fled New York to become a foreign correspondent. It was only after spending nearly a decade making a success of that — among other achievements, he opened the first ABC News bureau in the Arab world, in Beirut — that he returned to anchoring with the reporting stripes to go with his looks. Yet deviations from the network-anchor casting profile remained rare. Only good-looking, nonethnic white men were wanted for the evening news. Except for Walters’s short-lived evening-news career at ABC, no Jew has ever been anointed a network evening-news anchor. The later attempts to pair other female co-anchors of ethnic diversity, Connie Chung (at CBS) and Elizabeth Vargas (at ABC), with traditional male anchors came to naught. Until Katie Couric and Diane Sawyer in the past decade, there were no solo women anchors. And no network has ever named an African-American solo evening-news anchor — which makes the cultural and corporate politics all the more fascinating should Comcast seriously consider denying that official promotion to Lester Holt for the restoration of a white anchor caught breaking the rules.

Holt’s accidental ascent aside, NBC has been particularly enamored of anchors in the William Hurt–Broadcast News image. A decade ago, no one so much as whispered the thought that the doughy Tim Russert might be Brokaw’s successor at Nightly News, even though he had more impressive news chops than Williams. When Russert died, the obvious replacement for him at Meet the Press was Chuck Todd, a deep-dish political analyst in the Russert mold. But even for that Sunday-morning anchoring job, a nerdy-looking guy didn’t stand a chance at beating out the glib David Gregory, whose only visible advantage seemed to be that he looked like central casting’s idea of an NBC anchor. The contrasts between Russert and Williams and Todd and Gregory amounted to the Albert Brooks–versus–William Hurt conundrum all over again. (In the real-life case of Meet the Press, the nerd ended up inheriting the Earth anyway after Gregory flamed out.)

The reductio ad absurdum of the good-looking white-male anchor is David Muir, who last year succeeded Sawyer at ABC’s World News Tonight. His relatively modest reporting résumé didn’t even include a stint as a White House correspondent, usually a minimal posting required for a network anchor. Muir has already been christened “Ken Dahl” by Bill Maher. Appointed at age 40, he is the youngest evening-news anchor in half a century. But both his elevation and the Twitter-feed-paced broadcast he is anchoring are ABC’s open acknowledgments, if any were needed, that the anchorman as we’ve known him since the Cronkite era is done. Muir’s World News Tonight takes the network anchor’s role back full circle to its origins — a smooth newscaster hopscotching the world for headlines.

It’s not a show that needs a Cronkite or a Jennings or a Sawyer or a Brokaw. Arguably any ambitious newsman or newswoman would be overqualified to run it — or would balk at running it. Not for nothing did the most substantive heir apparent to Sawyer at ABC, George Stephanopoulos, dodge the anchoring slot at World News Tonight so he could retain his jobs as moderator of the Sunday-morning This Week and Good Morning America, which is a more powerful perch than the evening news as measured by profits, airtime, and audience demographic. And not for nothing were the title and authority of “chief anchor” at ABC bestowed on Stephanopoulos: He, not Muir, will be center stage for those anchor moments when breaking news actually breaks out and network news swings into 24/7 crisis mode. At CBS, the Evening News anchor who succeeded Couric, Scott Pelley, has sent his own signal that he regards anchoring as a secondary priority. He remains an active, not merely a nominal, correspondent at 60 Minutes, which has more (and more desirable) viewers, more journalism, and more clout than any network evening-news show, his included. Pelley seems to have taken to heart the disdain that 60 Minutes’ elders had for anchoring. Andy Rooney called it a “dumb job,” and Don Hewitt dismissed anchormen as “the television equivalent of disc jockeys,” spinning “the top 40 news stories.”

As has been demonstrated at 60 Minutes in particular, the most impressive, and bravest, practitioners of television news have rarely been anchors — as exemplified, many noted, by Bob Simon, the correspondent who died in a car crash in the aftermath of Williams’s suspension. Simon, who was held hostage for 40 days in an Iraqi jail during the first Gulf War, didn’t need to pose in pristine flak jackets or embellish his war stories; his exploits were on-camera. Unlike anchors, who tend to have what Andrew Heyward calls “manufactured authority,” he had “earned authority” that he didn’t wish to spend down at an anchor desk. It is the in-the-trenches, correspondent-based, anchor-free 60 Minutes model that the upstart Vice Media adapted for its television incarnation and that it will presumably stick with when it unveils its nightly-news show on HBO later this year.

When Brian Williams has spoken about why he wanted to be a network anchor since roughly the age of 6, he hasn’t emphasized reporting but the thrill of being everyone’s focus of attention during a national cataclysm. He’s fond of quoting Simon & Garfunkel: “a nation turns its lonely eyes to you.” But that iteration of the anchor reached its moral peak when America was looking for Father Knows Best reassurance in the Vietnam-Watergate era. No doubt some Americans of a certain age may still turn their lonely eyes to a patriarchal television anchor during a national disaster, but many more will be checking their phones.

That’s due not just to a technological revolution but to the erosion of confidence in nearly all American institutions and authority figures, including anchormen who seem unreconstructed relics of the Mad Men era. Williams is hardly unaware of this. The revelation that he had campaigned to succeed Jay Leno and David Letterman in their late-night gigs, and done so at the height of his success as an anchorman, can be read as the act of a man besotted by comedy, for which he discovered he had a modest talent. But more probably it was a panicked response to the reality that he was the last old-school anchorman standing. The new anchor no one had heard of at The Daily Show is likely to matter more than whoever is dodging bullets, real or imaginary, to bring us headlines — and lots of weather — on the Nightly News.

*This article appears in the April 6, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.