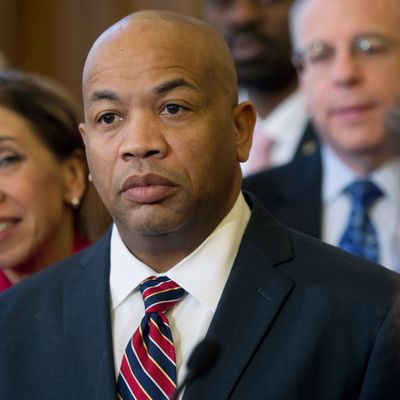

Shelly Silver hasn’t even gone to trial yet on charges that he took millions of dollars in bribes and kickbacks, and his replacement as speaker of the State Assembly, Carl Heastie, is already in the headlines for a dubious real-estate deal. Here Albany goes again, right?

Certainly Monday’s front-page Times story fit the narrative of New York’s state capital as a bottomless cesspool. In 1997, Heastie’s mother, Helene, was charged with embezzling $197,000 from a Bronx nonprofit health-care center. Prosecutors said she used some of the money to buy an apartment. After she pleaded guilty, as part of the bargain to avoid jail time, Helene Heastie agreed to sell the home and make restitution.

Weeks later, however, she died. Carl Heastie — who had earlier assumed a 99 percent interest in the apartment — says he was advised by an attorney that he was under no obligation to pay his mother’s restitution. So he didn’t. Heastie renovated the place, eventually selling it for $200,000 more than the original price and using the profits to help buy a home of his own.

There is more murk: The court never made Helene or Carl Heastie sign a formal forfeiture agreement. A judgment against Helene Heastie was never filed by the Bronx County clerk’s office.

Yet even the long arm of Preet Bharara can’t reach this one. Helene Heastie stole the money in 1995, and Carl Heastie sold the Bronx apartment in 2005. “The statute of limitations is five years after the commission of the offense,” says Duncan Levin, a former chief of the asset-forfeiture unit in the Manhattan district attorney’s office. “Because the paperwork didn’t get done and time has elapsed, there’s no way to seize the money. My guess is he’s legally in the clear. Being who Heastie is, the other question is about his ethical obligation.”

Especially because the ethical is deeply political in Albany these days. When Heastie suddenly became Assembly speaker in February, after Silver’s downfall, he promised a new attention to transparency and integrity. He’s vehement that he’s acted properly, during the apartment deal and ever since, both legally and ethically.

And Heastie’s side of the real-estate saga is both more complicated and somewhat more defensible than his initial legalistic reaction to the Times story. Helene Heastie’s lawyers claimed, back in 1997, that she was capable of covering the down payment on the apartment without the stolen money. Heastie, according to a spokesman, took control of the property after his father was diagnosed with cancer and his mother was partially paralyzed by a stroke, and that he worked two jobs to help cover his parents’ bills. Heastie says he paid $10,000 in restitution out of his own pocket. He put the apartment up for sale briefly; finding no takers, he paid $235,000 in mortgage installments, plus more for renovations. For those efforts, Heastie seems to feel he earned the $80,000 net profit when the apartment was finally sold.

“His father had died, his mother dies, there’s tremendous debt, and he has legal advice that he should go live his life. What is he supposed to do at that point?” Heastie’s spokesman, Michael Whyland says. “I challenge anybody to say they would have done anything different if they were faced with the same set of circumstances. It goes back to the fundamental question: Is the child responsible to pay the debt of the parent?”

It’s a fair question. As is whether Heastie should have benefited in any way from the messy chain of events. Heastie, before he ran for office, chose not to pay for his mother’s crime. Now, though, he’s one of the three most powerful politicians in the state — and Heastie’s promotion was the direct result of a corruption investigation. Even if the old facts are debatable, the new context makes him vulnerable.

Albany nerves are raw after two years of probes — first by Cuomo’s Moreland Commission, and now by Bharara and the U.S. Attorney’s office. So the concern in the Assembly isn’t about a dubious 20-year-old apartment transaction. It’s about whether this week’s Heastie story is only the beginning of the digging into his past, and of attempts to tar him by association.

Heastie, an accountant by training, rose through the political ranks of the Northeast Bronx Community Democrats, who were led by Larry Seabrook. Seabrook once tried to expense a bagel sandwich and a Snapple for $177. What earned the former city councilman and state legislator a five-year prison term, though, was funneling taxpayer dollars to friends, family, and phantom youth programs.

“I like Carl and think he’s a good person and pretty much a straight arrow,” an Assembly Democrat says. “But the Bronx is of concern. There had been some indication prior to the speaker’s election that there were some issues. So it shouldn’t have come as a surprise to anybody, that there might be an issue or two that might be raised, however tenuous.”

Heastie has engendered considerable goodwill during his first months in power, at least among his own Democratic caucus. In March, the rookie speaker held his own during state budget negotiations. He won the Assembly some positive press and strategic advantage by coming to early agreement with Governor Andrew Cuomo on new rules on the disclosure of outside income by legislators. Heastie has also delegated more responsibility and opened up internal Assembly deliberations to more members, a welcome change after years of Silver’s tight control.

The other reason that the Heastie story has mostly been shrugged off in Albany is that it arrived five days after a bigger Times-Bharara bombshell: that Dean Skelos, the Republican majority leader of the state senate, may soon be indicted. For the moment, the far greater anxiety is on the Republican Senate side of the legislature.

“How are all of the scandals going to affect getting things done?” an Assembly Democrat asks, before ticking off the big items looming in the spring’s legislative session — including the renewal of the city’s rent regulations, mayoral control of the schools, and tax breaks for developers. “This notion that people are distracted — on some level, that’s true. On the other hand, politicians are in fact professional people. And they put those things aside and let other professionals — their attorneys — deal with those other things.”

But the front-page spotlight on Heastie’s history hasn’t improved the Albany mood. “There’s a combination of weariness and embarrassment,” a state government insider says. There’s anger, too, that Bharara is willing to go after family members — Skelos’s son, Silver’s son-in-law — in his pursuit of misbehavior by public officials.

“The worry many of us have is that it will chase away the good folks of both parties, who care about public service, because they don’t want the taint,” the capital insider says. “They keep thinking it’s over. And then it’s not over.”