As Obamacare continues to operate successfully, conservative elites have renewed their pleas for the party to develop an alternative beyond demanding the law’s repeal. The trouble is that anti-Obamacare dogma sits so deeply at the GOP’s core that any discussion of health care must pay fealty to their belief that the law has failed utterly. The Republican Party in the Obamacare era is a doomsday cult after the world failed to end. Its entire analysis of the issue is built upon a foundation of falsehoods.

Michael Tanner, a health-care analyst at the Cato Institute, has a column for National Review usefully summarizing the most current iteration of anti-Obamacare talking points. Most of Tanner’s piece is devoted to arguing for alternative proposals, but he begins with the ritual incantation of Obamacare doomsaying. Tanner does not argue that Obamacare is wrong because conservatives philosophically object to using taxation and regulation to transfer resources from the rich and healthy to the poor and sick. Instead he makes eight substantive claims about the law’s impact on health-care access. Every single one of them is overblown or demonstrably wrong.

Here’s Tanner’s litany of failure:

Millions of Americans were forced to change insurance plans, and others found themselves pushed into smaller networks with few choices of providers. Premiums rose. Businesses, laboring under the higher costs imposed by the law, have slowed growth; many have delayed hiring, or shifted workers from full- to part-time. The potential impact on the quality of care remains troubling.

Let’s take these claims in order.

1.“Millions of Americans were forced to change insurance plans.” The specter of mass dislocation was a major anti-Obamacare talking point at the end of 2013 and 2014. The new health-care regulations banned a lot of unpopular practices, like lifetime limits on how much an insurer would pay, or discriminating against preexisting conditions. So it is true that many people who held insurers in the old, barely regulated insurance market needed to find new plans. On the other hand, that market had enormous year-to-year churn anyway. The main way for insurers to make money was to exclude customers who were likely to get sick, so they threw people off their insurance all the time.

We now know that the new churn created by Obamacare was much smaller than conservatives insisted at the time. A recent study by the Urban Institute found that policy cancellations were not “millions,” but under a million. As the authors explain:

These estimates suggest that policy cancellations caused by noncompliance with the ACA were uncommon in 2014 in both the nongroup and ESI markets, and the number and rate of cancellations in the nongroup market in 2014 was far smaller than in 2013. The nongroup market has historically been characterized by high volatility: an analysis of pre-ACA nongroup coverage patterns from 2008–11 shows that only 42 percent of nongroup enrollees retained their coverage after 12 months.

2. “ … and others found themselves pushed into smaller networks with few choices of providers.” It is true that many people who enrolled in the new exchanges have insurance plans that limit their choice of doctors and hospitals, which is called “narrow networks.” There is no evidence that Obamacare caused this. The law overwhelmingly covers people who had no insurance to begin with. You can’t be “pushed” into a “smaller” network when your previous network was nonexistent.

As Jonathan Cohn laid out in an excellent and balanced explainer on this issue, insurers have been using narrow networks to control costs for decades. “That’s been the case for decades,” Larry Levitt told him, “The only real connection to the Affordable Care Act is that the health reform law is making insurers compete for customers more aggressively.”

If narrow networks are spreading, it is because the Obamacare exchanges are bringing consumer choice into the system. Overwhelmingly, the customers enrolling in plans with narrow networks are not being “pushed” so much as they are choosing them. As a McKinsey study from last year found, 90 percent of eligible customers have access to broader networks of doctors and hospitals. But most customers choose plans with narrow networks because they would rather not pay the higher premiums required to access broader networks. If we think narrow networks are inadequate, one response would be to require insurers to include more doctors and hospitals in their plans, but this would add to costs — an odd argument for a conservative to make.

3. “Premiums rose.” It is true that some people will pay higher premiums. If you previously held a catastrophic plan that covered little to none of your medical expenses, you may now be paying higher premiums in return for having insurance that covers the cost of medical care. Likewise, if you were uninsured and now have coverage, your new premiums are now higher than your old premiums, which were zero. This is exactly what the law intended to do.

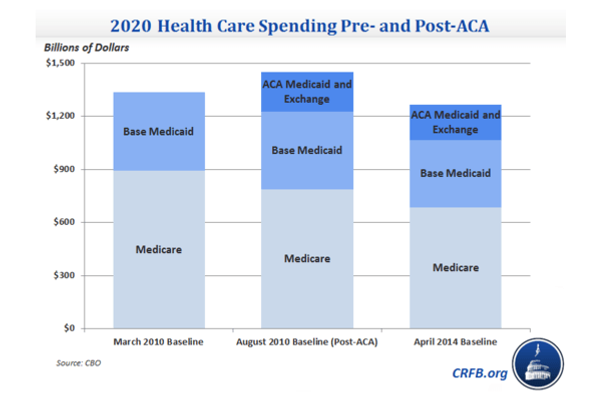

The argument between the law’s supporters and critics centered on whether it would succeed or fail at its goal of restraining health care inflation. Historically, the cost of health care has grown at a much faster rate than the cost of other goods. Since Obamacare has taken effect, that trend has sharply reversed itself. Analysts debate the degree to which this enormous success is the result of the new law’s reforms versus outside factors. But the cost of Obamacare insurance premiums has come in well under official projections.

Tanner himself asserted that Obamacare would absolutely increase the cost of health care. “While we were once told that health-care reform would “bend the cost curve down,” we now know that Obamacare will actually increase U.S. health-care spending,” he wrote in 2012. This has been proven false. The federal government is spending less, even with the coverage expansions provided by Obamacare, than it was projected to spending before Obamacare became law:

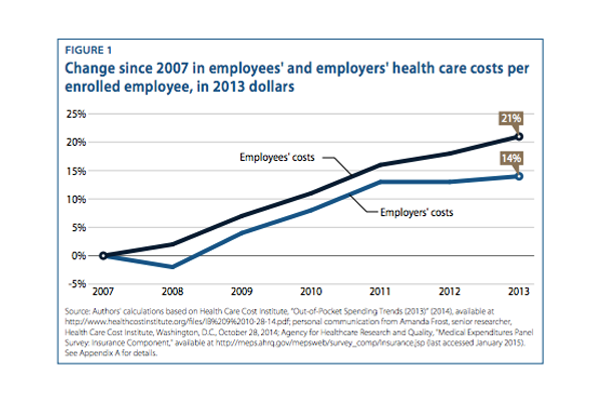

4. “Businesses, laboring under the higher costs imposed by the law … ” This is the opposite of the truth. The cost of providing health care to employees for business, after years of rapid growth, has stayed unusually flat:

5. “ … have slowed growth.” Actually, 2014, the first year of Obamacare’s implementation coincided with the fastest growth in GDP since the start of the recession.

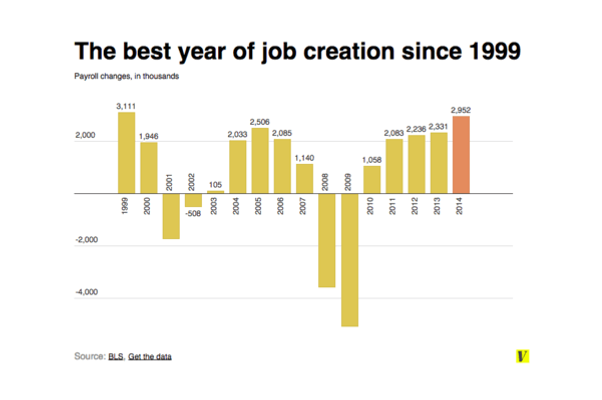

6. “many have delayed hiring … ” In fact, 2014 was also the best year for job creation, not only since the recession but since 1999.

7. “or shifted workers from full- to part-time.” Nope, the share of part-time workers has also fallen since Obamacare took effect.

8. “The potential impact on the quality of care remains troubling.” This is a really vague statement. Measuring the quality of health care is nearly impossible in general. What’s more, tanner’s formulation has not one but two weasel words (“potential,” “troubling”) that distance him from any verifiable claim.

That said, there’s plenty of evidence that the Affordable Care Act is improving the quality of care. The percentage of Americans delaying medical care for financial reasons has dropped sharply. The rate of hospital-acquired infections (a key target of the law, which changed hospitals’ financial incentive in order to drive down infections) has fallen. Customers who bought insurance through the exchanges report high levels of satisfaction with the quality of their care. One study found that Obamacare is saving around 50,000 lives a year; after President Obama cited the figure, Washington Post fact-checker Glenn Kessler set out to debunk the claim, only to determine that it checked out.

**

This is the reality that the entire Republican Party has failed to come to grips with. The American health-care system before Obamacare was an utter disaster — the most expensive in the world and also the only one that denied access to millions of its own citizens. Obamacare set out to change those things, and it has worked.

There is one remaining indictment of the law that Tanner makes, and it’s true. “The law remains extraordinarily unpopular, with opponents topping supporters by nearly 11 percentage points, according to the latest Real Clear Politics average,” he argues. It is notable that opponents of Obamacare have fixated on the law’s poor polling. In a recent column, Reason’s Peter Suderman quibbles halfheartedly with the law’s demonstrable success in carrying out its goals — suggesting that the astonishing drop in medical inflation may be owed to outside forces — before reveling for six paragraphs in his major point, which is continued lack of public approval. “Obamacare is simply not well liked,” he concludes, “This is the political reality — and President Obama still refuses to embrace it.”

It is telling that, having lost every substantive argument about the law’s operation, their sole remaining refuge is an argument about its perception. It’s true: Their lies got halfway around the world before the truth could get its pants on. Indeed, if you google most of the factual disputes I discuss above, you’ll get a lot more hits from conservatives making hysterical and false predictions than you will find from reports showing those predictions failed to come true. Those myths still hold enormous sway over public opinion. Far more Americans believe Obamacare has death panels, which is false, than believe its costs have come in under projections, which is true. Conservatives have won the propaganda war over Obamacare. The trouble is that they think this is an indictment of Obamacare, when in fact it’s an indictment of them.