When Barack Obama first appeared on the scene as an underdog challenger to Hillary Clinton, conservatives welcomed him as a refreshing, relatively moderate alternative. Then they decided Obama was actually a left-wing extremist, in comparison to the moderation of the Clintons. As Hillary Clinton prepares to take the helm of the Democratic Party, the Republican task is now to formulate a new line, according to which Obama moved his party to the left, and Hillary Clinton threatens to move it even further left. Peter Wehner, a former Bush administration strategist, makes the case in the New York Times today. His case is not strong.

It is true that underlying social trends have moved both parties to the left on some social issues. In 2004, same-sex marriage was such a radical concept that George W. Bush ginned up a referendum on the issue to help win Ohio, and Howard Dean refused to endorse it; today, Republicans are terrified to bring it up. The growth of the Latino and Asian-American electorates has likewise pulled many Democrats and some Republicans left on immigration. And the waning of the rise in violent crime that began in the 1960s has made both parties reconsider their rigid stances on criminal justice.

But Wehner offers up a far more ambitious thesis. He claims that Democrats have moved far to the left across the board since the Clinton administration. Indeed, he argues “in the last two decades the Democratic Party has moved substantially further to the left than the Republican Party has shifted to the right.” After stating this thesis, Wehner devotes the rest of his column to analyzing the Democrats, completely ignoring the other half of his equation, which is its most provocative element.

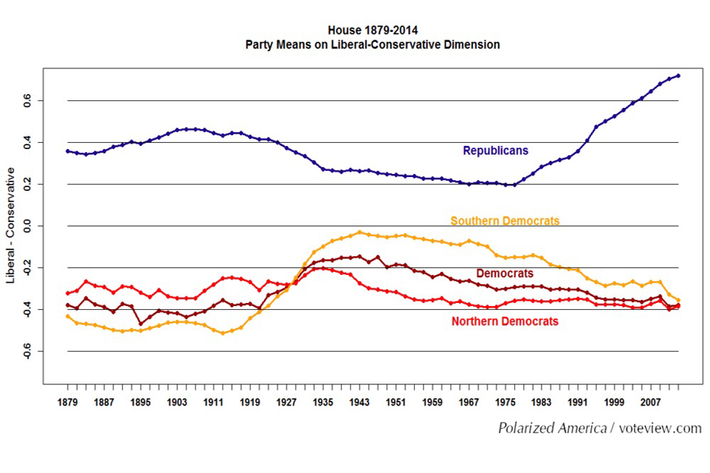

Wehner likewise ignores the studies made by political scientists to answer this question quantitatively. The most commonly used measures, DW-NOMINATE scores, show the precise opposite of what Wehner claims. Republicans have moved extremely far right, and Democrats slightly to the left, and the latter shift is a function of the extermination of its conservative white southern wing.

Of course, quantitative measures can be flawed. But Wehner does not explain his disagreements with the quantitative measures, or mention their existence. Instead, he cherry-picks a handful of issues where, he claims, the Democrats have moved far left — again, ignoring the GOP’s right-wing shift. Most of the issues Wehner cherry-picks (aside from the aforementioned shifts on same-sex marriage, immigration, and criminal justice) either fail to bolster his point, or actively undermine it.

“One of the crowning legislative achievements under Mr. Clinton was welfare reform. Mr. Obama, on the other hand, loosened welfare-to-work requirements,” he writes. In fact, Obama has undertaken very minor tweaks to the welfare-to-work requirement that, according to Ron Haskins, a Republican staffer who worked on the bill, do not undermine its character or goals. (Clinton himself was far from an absolutist defender of the original legislation, which he called at the time a “good bill wrapped in a sack of shit.”)

Wehner asserts, “Mr. Obama is more liberal than Mr. Clinton was on gay rights, religious liberties, abortion rights, drug legalization and climate change.” The part about gay rights is correct. The rest lack any substantiation. On climate change, the Clinton administration attempted to impose a carbon tax in 1993, but failed, and supported the Kyoto Treaty but faced overwhelming opposition in the Senate. Obama, claims Wehner, “has focused far more attention on income inequality than did Mr. Clinton, who stressed opportunity and mobility.” Actually, both Clinton and Obama stressed inequality and mobility alike. President Clinton endlessly promised to make the rich “pay their fair share,” while Obama has stressed opportunity and mobility.

“While Mr. Clinton ended one entitlement program (Aid to Families With Dependent Children), Mr. Obama is responsible for creating the Affordable Care Act, the largest new entitlement since the Great Society,” writes Wehner. “He is the first president to essentially nationalize health care.” Clinton also created an entitlement (the Children’s Health Insurance Program, in 1997). More important, Clinton attempted to nationalize health care. The fact that Clinton’s plan failed in Congress while Obama’s succeeded hardly makes Obama more liberal.

“Mr. Clinton lowered the capital-gains tax rate; Mr. Obama has proposed raising it,” writes Wehner. It is true that Clinton agreed to lower the capital-gains tax, but not because he wanted to lower it. He traded that for the aforementioned children’s-health-insurance entitlement.

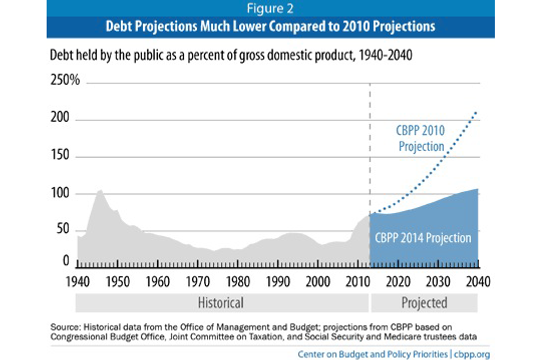

“Mr. Clinton cut spending and produced a surplus,” writes Wehner. “Under Mr. Obama, spending and the deficit reached record levels.” In fact, both Clinton and Obama had similar fiscal policies. Both increased the top income tax rate to 39.6 percent and oversaw cuts in discretionary spending. Obama did inherit a deficit projected to top a trillion dollars before he stepped into office. But he enacted a number of policies, such as ending some of the Bush tax cuts and the Bush wars, and health-care reform, which have dramatically reduced the long-term deficit:

It is true that Obama, unlike Clinton, has failed to yield a surplus. Of course, Wehner used to point out that the Clinton surplus was the temporary product of a tech bubble.

“In foreign policy, Mr. Obama has shown himself to be far more critical of traditional allies and more supine toward our adversaries than Mr. Clinton was.” These are the exact same criticisms conservatives made of Clinton during the Clinton administration. The neoconservative Richard Perle in 1996 lambasted “the nearly chronic tendency of the Administration to abandon any policy that encounters even mild opposition, guarantees that adversaries are not deterred — nor are allies assured.” The centerpiece of the conservative claim that Obama criticizes his allies is Israel, and the actual basis for this is that Israel’s government has abandoned its support for a two-state solution, a fact Clinton himself has likewise acknowledged.

Wehner asserts that “Obama’s inner progressive has been liberated,” citing “his veto of legislation authorizing construction of the Keystone XL pipeline,” but allowing his approval of oil drilling off the Alaska coast as an “exception.” Another, more accurate way to put this would be that Obama approves of some fossil-fuel projects but not others, just as Clinton did. (Clinton infuriated conservatives by vetoing drilling in the Arctic Wildlife National Refuge, the Keystone Pipeline of its day.)

The Democratic Party’s social profile has certainly changed under Obama. The country is more diverse and socially liberal, and the party has changed with it. But the notion that Obama, who staffed his administration with Clinton-era advisers, has fundamentally abandoned Clinton’s ideological approach to the role of government is lacking in any evidentiary support. Obama has enacted more dramatic policy changes than Clinton did, but this is not because he had dramatically different goals, but because he had dramatically more success in enacting them. (This, of course, is another reality Wehner has repeatedly denied.)