Jean Nouvel Is a Master Without a Style

Talking to the <em>architecte terrible</em> who can’t stand one of his new buildings.

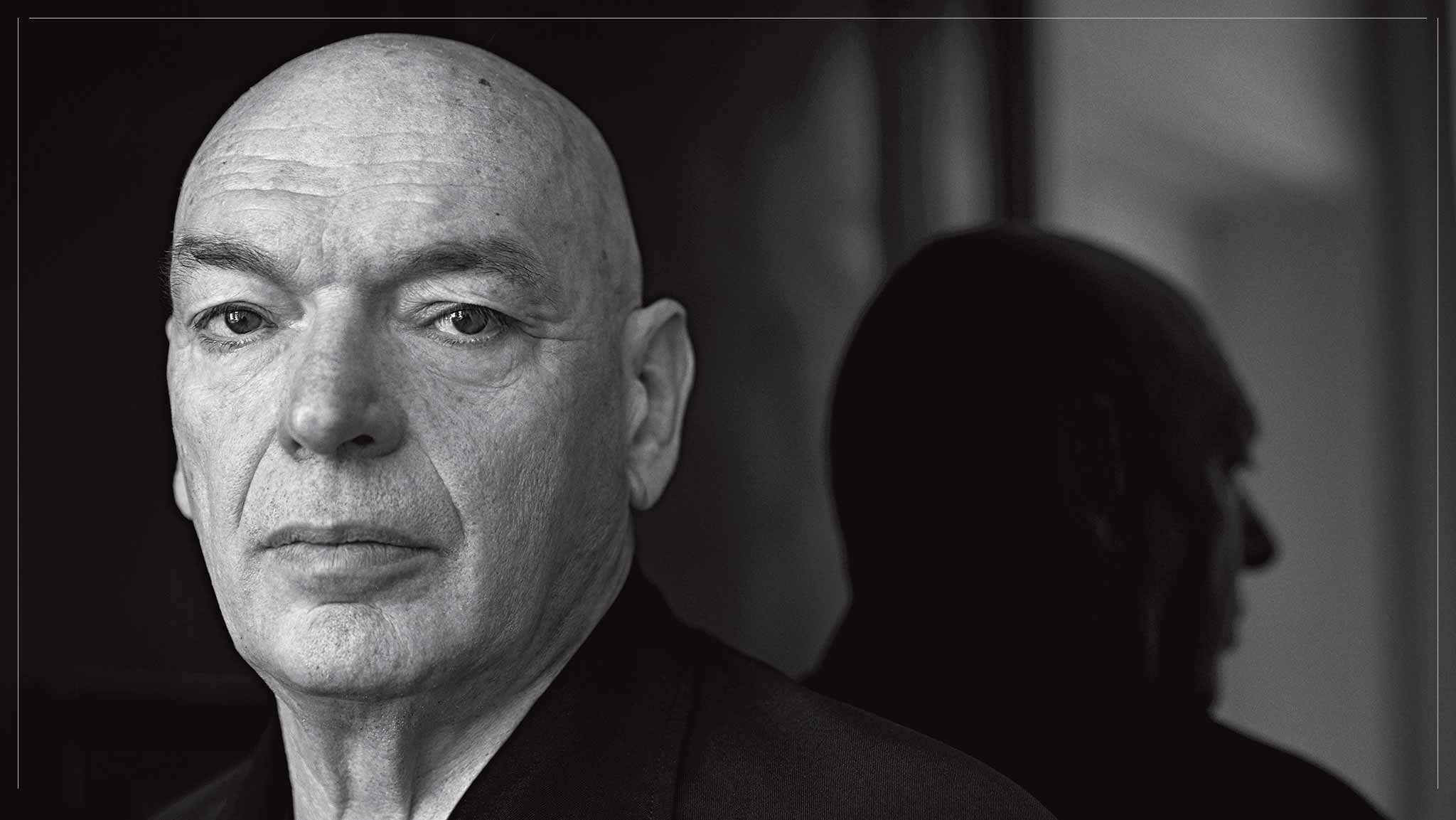

It’s Fashion Week on the Rue Saint-Honoré in Paris, and a black-clad mountain of a man lumbers through a hotel lobby full of preening gazelles. His long coat sweeps a Champagne flute off a coffee table and into a young woman’s lap. He makes vague blotting motions, as if he could soak up the Champagne remotely, then gives up and moves on. His assistant grabs a napkin and administers a few firm dabs and profuse apologies. She, too, moves on, following her boss into a private dining room for a working lunch. A few minutes later, a waitress pops in with an update: The young woman is fine, she’s been given a new drink, and, in fact, “Elle est ravie que ça soit vous” — she’s delighted to have been soaked by one of France’s cultural treasures, the architect Jean Nouvel.

In a nation that makes celebrities of its philosophers and literary critics, Nouvel is more than a designer of buildings; he’s a curator of French architecture’s cultural ambitions. His Philharmonie de Paris, which opened in January, embodies the desire to bridge the chasm between elite and popular music — or, depending on your politics, it’s a state-sponsored boondoggle squandering fortunes on deluxe entertainment. The Musée du Quai Branly, a rust-colored museum of non-Western culture that crouches in the greenery near the Eiffel Tower, plunges into France’s long and fraught debates over colonialism, Orientalism, and primitivism. His Louvre Abu Dhabi will bring a new cultural juggernaut to the Persian Gulf with the help of a French museum consortium and a French brand name.

“My approach to architecture is tied to my European culture, my French upbringing, and my Parisian trajectory,” he says, studying the label on a bottle of Châteauneuf-du-Pape. “But I think it’s essential to merge an insider’s knowledge with an outsider’s perspective. Otherwise, you take too much for granted, and you fail to see what’s possible. Sometimes when you think you know a city, you don’t really know it at all.” Nouvel has a tendency to speak in gnomic generalities, but what he seems to mean is that intimacy with Paris has given him the grounding to work anywhere. Weaving around the constraints of history prepared him to be inventive with New York’s byzantine zoning code, and now, after nine years of dithering, his supertall 53 West 53rd Street, informally known as the MoMA Tower, is finally under construction. His “Parisian trajectory” has also propelled him into unexpected orbits. Ever since he came out of the blue to win a competition in 1981 for the Institut du Monde Arabe on the Left Bank, he has been a de facto interpreter of Islamic architecture. And not just in the West: When Qatar needed a national museum, it turned to him. Now he’s about to extend that idea to New York, designing an Islamic museum on Park Place, a successor project to the notorious “ground-zero mosque.”

What Paris has not bequeathed him is a style. He and his Pritzker-winning peers regularly come up against one another in purportedly anonymous competitions. The juries usually can guess whose work they’re seeing. Whereas Frank Gehry’s crinkly crumples and Zaha Hadid’s zip ribbons are instantly recognizable, Nouvel’s buildings are so distinct, and redefine their genres so thoroughly, that they don’t seem like products of the same imagination. “If they can’t figure out who it is, that means it’s me,” he says, laughing.

This ritualized global scavenger hunt for the building as artistic statement drives many critics crazy. To them, Nouvel and his ilk are irrelevant hucksters, sucking up resources to create buildings that are environmentally irresponsible, disdainful of their surroundings, indefensibly expensive to build, flamboyantly impractical to use. “Future architects will look back at our times astounded by our confusions, gullibility and inability to exercise critical judgment,” writes the British critic Peter Buchanan. It’s true that the planet has recently acquired an extensive collection of white elephants, some built at immense cost and then abandoned, others never finished at all. (Herzog & de Meuron’s “Bird’s Nest” Olympic Stadium in Beijing sits mostly unused and empty.) Yet to treat Nouvel’s work as nothing more than arrogant folly is to dismiss one of the era’s great practitioners. What makes him interesting is the interaction of his talent and his flaws — the fact that an architectural genius can also be an egomaniacal sculptor.

Lunch is an important ritual in his workday, a discussion lubricated by copious amounts of wine. Often, it’s the first time his staff gets to see him, since he spends mornings in solitude. “I wake up, perform my little ablutions, then get back into bed with my eye mask on and my earplugs in, and I work. I imagine. I visualize. I create a film in my head.” Nouvel insists that there’s nothing meandering about these sessions: They’re intensive bouts of problem solving, preceded by weeks of preparation — but who’s to say if he dozes off? Before a morning in bed, he says, “I have to upload to my brain all the research, the constraints, the parameters. If I find that some parameters are missing, I get furious. Because then I can’t do my work.” By early afternoon, he’s ready to communicate the fruits of his meditation, sometimes with a rough sketch, more often with words. He and two or three of his staffers frequently retreat to his house in Saint-Paul de Vence, a picturesque hill town a few minutes from the Côte d’Azur, for what he calls séminaires de brainstorming that can consume as much as a third of the year. It’s calm there in the south, he tells me in a wistful way that makes me think of Baudelaire: “Là, tout n’est qu’ordre et beauté, / Luxe, calme et volupté.” (“There, all is order and beauty, / Luxury, peace, and pleasure.”)

It would be easy to deduce from this process that he dictates vague visions that his staff of 140 employees from 19 countries then converts into buildings with actual plumbing. That impression doesn’t survive a day I spend tagging along as he patrols his warren of offices, trundling from workstation to workstation and making his underlings tense up. He hovers and prods, often until 2 a.m., undoing three days’ work with a casual harrumph. His longtime employees learn to read his moods, which tend toward the saturnine. During his wanderings, he checks in on the progress of a hotel and convention center in Brussels, a conference building at the University of Chicago (an entry for a competition that he will later lose), his third stab at building a Paris skyscraper — on and on, like a traveler touring an imaginary city full of bright colors, ornamental screens, intricate patterns, and filtered light. He lingers for a while at one architect’s shoulder, fussing over dreamy renderings of the National Art Museum of China, in which figures glimpsed in a window seem to fade magically into the thickness of a stone wall. If the hyperdetailed imagery that chugs out of the office’s printers looks like the product of a Proustian reverie, it’s because that’s exactly what it is.

Nouvel was born in Gascony, the son of provincial teachers who deflected their artistic child away from painting and into the theoretically more stable life of an architect. He arrived at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1967 and graduated three years later full of scorn for official aesthetics. He allied himself with distinguished rebels: the architect Claude Parent and the urban theorist Paul Virilio, who explored the toppled and shattered bunkers left by World War II and extrapolated an architecture of ramps and tilted walls. From the beginning, the young Nouvel was an organizer, caught up in the reformist spirit of the times. He co-founded an architects’ union, and the group Mars 1976, which aimed to undo the top-down planning principles that were turning every medium-size town in France into a carbon copy of the others. Even then, he was biting the hand of a generous government.

You might think that today such a laureled artist would do nothing but wait for a sheikh to call. That does happen from time to time, but at 69, Nouvel still struggles to keep his practice on a financial footing, still hustles for jobs, and still participates in the grueling, low-yield process of competitions. Partly that’s how the business works. (“The best business plan for an architect is not to be an architect,” an architect once told me.) In 1993, a bust in the French real-estate market doomed the skyscraper that he had expected to be his masterpiece and pushed the firm into bankruptcy. Nouvel turned to an old friend, Michel Pélissié, who rescued the business and ran it with a steady hand. By 2008, Nouvel was working not only on prestige projects but also on capitalist icons in desert cities: the “Green Blade,” a condo slab that looked like an enormous leafy iPhone rising above Century City, and a new MGM casino in Las Vegas. “We were flying high, we had doubled our space, we had hired new staff,” Nouvel recalls. Then came the recession. The two projects were scrapped on successive days. “And that was the beginning of the crisis. Three-quarters of our projects collapsed: Boom, boom, boom, boom, boom. Finished. Good-bye.”

The partners, friends for more than 40 years, started squabbling over money. Their relationship fell apart in 2012, with Nouvel accusing Pélissié of having pillaged the firm and Pélissié portraying his old partner as a naïf. “After his Pritzker, Jean lost all sense of reality,” Pélissié told Le Parisien. “Once, he listened to me. If a client said, ‘Nouvel’s changing something, and it’s going to cost us double!’ I was able to make him see reason. But then a while ago he started listening only to what was going on in his head.” Perhaps only in France could a lawsuit include the accusation that a CEO had beggared the company by paying for more than 14,000 bottles of wine that were both absurdly marked up and never delivered.

At the moment, Nouvel is consumed by disappointment over the Philharmonie, a divisive undertaking whose budget ballooned from a laughable $160 million proposal to $455 million by the time it opened, cementing his reputation for fiscal irresponsibility. When a left-wing government inherited the project from its right-wing predecessor, a fancy concert hall was judged to be a waste and would have been squelched, except that abandoning a half-finished ruin seemed even more wasteful. In order to control the damage, the government’s appointed overseer, Patrice Januel, imposed budget cuts and design changes. The battle of similarly named egos fascinated the French press for years: Januel versus Jean Nouvel.

For decades, the now-90-year-old composer Pierre Boulez has been calling for the concert hall to be redefined, not just as a sacramental space for symphonies but as a round-the-clock complex, constantly alive with children and amateurs as well as professionals and connoisseurs. Nouvel translated Boulez’s vision into a combination of school, museum, auditorium, and community center, located in the Parc de la Villette, near the working-class district of Pantin. The Périphérique, the city’s multilane ring road, runs — or rather, crawls — right by, sundering the core from the impoverished banlieues. That highway has always been a psychological moat. The Philharmonie has taken on the task of bridging it with music.

To accomplish that feat of sociocultural engineering, Nouvel produced a stack of bent and folded planes, cut across with ramps, that look like the product of some epochal tectonic event. One vertical slab forms a giant screen that shows drivers on the ring road what they’re missing; it’s a live-feed billboard for classical music. The building, in its endearing awkwardness, is not an austere temple of art but a structure that invites the public to walk on it, mock it, use it, and even gently abuse it. Inside, it’s a whorl of surfaces studded with little wood blocks that function the way plaster cherubs do in 18th-century theaters, diffusing the sound to give it a soft glow. I heard the Orchestre de Paris perform a program that covered a vast acoustic territory, from the soloists’ murmurings in Beethoven’s Triple Concerto to great cloud-parting shafts of sunlit brass in Bruckner’s Ninth. The sound was so clear it seemed almost digital, with a light, warm wash of resonance. Boulez has yet to attend a performance there, but he might be pleased at what his polemics have wrought.

Nouvel, on the other hand, is miserable. At almost any mention of the Philharmonie, his shoulders slump and he passes one large hand over his glabrous scalp. Months after the opening, it was still a construction site, where workers waited each evening for the last notes to die out before rushing in to labor all night. He still despairs at all the corners cut, the mediocre workmanship, the design details that have been quashed, making the façade seem jittery and indistinct. The auditorium ceiling is plaster instead of wood. The lobby carpeting … apocalyptique! I show him a snapshot I took in the men’s room of a sign posted above the urinal: EAU NON POTABLE. Don’t drink where you pee. He breaks out in a mournful laugh.

Nouvel might have put on a brave smile and chipped away at these details in closed-door conversations, but that is not his way. He attacked — in the pages of Le Monde and in court. The hall opened a week after the Charlie Hebdo massacre, a time when Paris needed succor, unity, and a celebration of humanism. Nouvel boycotted opening night. A few weeks later, he filed a lawsuit, claiming that the unfinished hall displayed “contempt for architecture, for the profession and for the architect of the most important French cultural program of the new century.” The court was flummoxed, ruling that it had no way to determine when an architect’s work is no longer really his.

The experience has been tough on his pride, which he wears as ostentatiously as his black fedora. During an afternoon when we visit several of his Paris buildings, he nods benevolently to various fans and fawners, and he mentions casually that the previous evening, he stayed up late thumbing through a new book about him titled Prince Jean. But his boasting comes wrapped in insecurity. He’s waiting anxiously to hear about a possible meeting with the Chinese president Xi Jinping to discuss his designs for the National Art Museum of China. “The president of China wants to talk to me, and here I can’t get the ear of a two-bit bureaucrat,” Nouvel says. “I guess it’s true, no man is a prophet in his own land.”

Another day, another lunch. Nouvel, accompanied by the Lebanese-born architect Hala Wardé, a longtime collaborator, and two other senior staffers, ducks through a velvet curtain into a small private dining room and immediately starts rearranging the tables. Ordering takes precedence over talk, but when the waiter finally disappears, Wardé spreads out a sheaf of drawings, diagrams, and construction photos of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which Nouvel will be visiting in a few days.

“There’s an executive meeting, all the VIPs will be there, and they want to celebrate progress on the dome,” she says. The waiter comes back with the wine, and Wardé pauses while Nouvel examines the label. Then she continues: “Everyone is pleased, and they want to know you are too.”

“Which means they want concessions,” Nouvel grumbles. “What are they asking for?”

As they work their way through her list — the thickness of paving stones, the gangplanks in the marina, the seating in the bar area, the placement of cooling ducts, whether ceiling panels in the museum lobby should be removable or fixed — Nouvel interprets each question as a money-saving assault on his design. He sits impassively, occasionally glancing from his food to a drawing that the other architects brandish like courtroom evidence. The contractor has specified a revolving steel gate like the ones in the New York subway. Nouvel’s staff has designed a more elegant — and more expensive — alternative.

“So you want to cage people in the nicest possible way?” Nouvel asks. “What’s the cost difference?”

About $40,000, Wardé estimates.

“That’s not much. The cost of a small car.”

“Actually, that’s a really nice car,” Wardé protests. “A Mercedes, at least.”

Nouvel waves the issue away with his wineglass. “A cage is a cage. I don’t really care.”

His responses are tactical: Fall back on the turnstiles; hold firm on the ceiling panels. As the conversation gets more and more technical and the minutiae minuter, Nouvel mentions that I have visited the Philharmonie. Wardé shudders. “It’s terrifying,” she says. “You see the kind of questions we discuss, and you realize what can happen if you let go.”

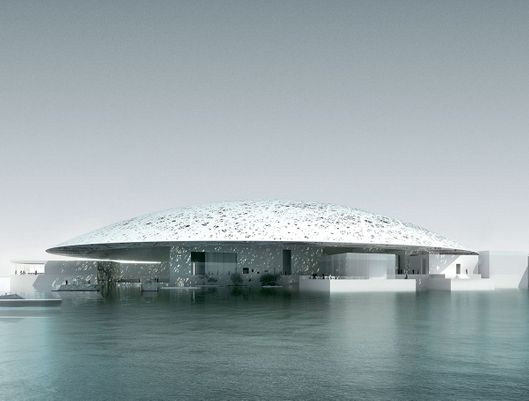

The Louvre project sounded insane from the beginning: Turn a desert island off the coast of Abu Dhabi into a new Venice, with cultural institutions arrayed along a grand canal. The Emirates’ Tourism Development and Investment Company (TDIC) asked Zaha Hadid to design a performing-arts center, Norman Foster to build a national museum, and Frank Gehry to produce a new Guggenheim. It gave Nouvel a central site for a museum of world civilizations. Even before Nouvel helicoptered to the barren patch of sand — and long before he knew what art the museum would contain or where it would come from — he sketched an idea: a cluster of sugar-cube-like blocks beneath a shallow dome. As the design developed, the white gallery buildings, separated by seawater and linked by walkways, came to resemble an Arab city on steroids, the huddled houses of a medina inflated to palatial proportions. A perforated cupola, supported by four thick columns hidden inside the buildings, seems to float above, a forest canopy in a treeless region. The Arabian sunshine, after dodging eight layers of woven steel, throws luminous splashes on the walls and floors, mottled patterns that change minute by minute. It’s a modern incarnation of the mashrabiya, the ornamental screen that’s common in Islamic architecture.

Though Nouvel chafes against the relative powerlessness of the architect, it can also be a useful defense, particularly when it comes to the treatment of construction workers on the Louvre site. To the rest of the world, Nouvel may seem to be building a temple of vanity on someone else’s dime. To the client — a complex tangle of the TDIC plus the Louvre plus all the contractors — he’s a deluxe version of a hired hand, paid to provide a service and go home. When I press him about the workers’ conditions, he shrugs. “They took me on a tour of their housing, and it looked fine,” he says. “It’s not in anyone’s interest to exploit workers.” Which actually means it’s not in his interest to know any more than he has to.

Last November, Wardé presented Nouvel’s Louvre designs at a Columbia conference about the architecture of the Arab city. It was rough going. What, some participants asked, did Nouvel think he was doing, importing his Parisian-flavored Orientalism into a part of the world he barely knew? When I ask him a similar question months later, Nouvel recognizes that building a Louvre on a sandbar is un peu fou — “a little crazy.” He summarizes the criticism in tones of mock outrage. “What’s wrong with these people that they want to create a system of grand museums? That’s Europe, that’s us! They don’t even have a collection! They have to buy everything from scratch! I find that an incredible reaction,” he continues, pointing out that a little over a century ago, another newly wealthy, culturally insecure city was frantically founding museums and shopping to fill them: New York. “All cities, when they reach their golden age, construct for their people and for their culture, to bear witness to their epoch. It’s perfectly logical.”

One of the paradoxes of Nouvel’s architecture is that while clients come begging for uniqueness — and some critics see a portfolio of sore thumbs — he lets the surroundings shape his buildings. He proudly calls himself a contextualist, before going on to clarify that the term doesn’t — or shouldn’t — mean replicating existing styles, but rather letting the location’s idiosyncrasies permeate the design. The vast majority of today’s architecture, he fumes, is parachuté: generic forms inserted into a site without regard to climate, culture, or context. “We’re in an epoch of savagery. Developers have usurped the role of architects, so who will defend the pleasure of living in a particular place? It’s a fundamental question. Places are not interchangeable. Living somewhere means everything you experience outside, the people you meet, the way you move around — the whole atmosphere of a city in all its complexity.”

Still, what Nouvel calls contextualism others see as cultural cliché. “If you’re in Africa, suddenly you start doing tribal patterns,” says Amale Andraos, the dean of Columbia’s architecture school, “and in the Middle East you use the medina.” She acknowledges, though, that Nouvel deploys his references virtuosically. “He does his research, and the Islamic motif is not just a pattern that gets slapped on at the end. The screen really performs the way it was always supposed to, creating transparency and fragmenting light.”

On our last evening together, Nouvel and I visit the Fondation Cartier, a building that distills the City of Lights into a structure of almost pure luminescence. At the opening cocktail party for a Bruce Nauman restrospective, artists, collectors, and art-world groupies press together in the glossy see-through art box that Nouvel designed more two decades ago and hasn’t lost its diamondlike brilliance. Into this sparkling bubble shuffles the architect, looking, in his dark hat and coat, like a 3-D silhouette, or the looming killer’s shadow in The Third Man. He’s pleased to see the place so animated. Many architects imagine their creations pristine, free of humans, clutter, and trees. Nouvel, though, seems to like making regular visits to his projects as they age and alter and fill up with new generations who assume that the landmarks they grew up with have just always been there.

A couple of months later, Nouvel is in New York, and we meet for a quick lunch in a Soho hotel. Since I last saw him he’s been to Abu Dhabi, Qatar, China, and Chicago, and now he’s eager to get back home. “For architects who think that their primary job is to get work, travel is good. If you think that your primary job is working, it’s not so good.” His gaze wanders to the wall of the hotel lobby and lingers on a bright, seemingly random streak of white on white, which he mistakes for a design detail but turns out to be a glint of sunshine bouncing in from the street. “That’s marvelous,” he says. “Our job, as architects, is to observe an accident like that, then reproduce it on purpose.”

Nouvel has made a relatively light mark on New York, with just two residential buildings — 40 Mercer Street, a deluxe riff on the theme of the cast-iron Soho building, and 100 11th Avenue, with its convex, disco-ball façade of varicolored windows, plus the Brooklyn Bridge Park lagniappe of Jane’s Carousel. But he’s about to join a different club of architects: those with access to the upper reaches of the Manhattan skyline. His 1,050-foot MoMA Tower is finally going up, a bundle of crystalline spears shooting out of midtown.

This is one stack of plutocrat pads that earns its spot on the skyline. When it’s built, the tower will seem like an object in motion, its palette edging into silver and gold on the way to the clouds. Three pointy slivers fit together like bits of slate, bound by diagonal concrete straps, a motif doubled on the façade by aluminum panels. Despite his bitterness that Amanda Burden, when she was planning commissioner, cut 200 feet off his design, Nouvel draws energy from Manhattan’s restrictive zoning and rigid grid. “Architecture is the art of utilizing constraints. If you can do whatever you want, then it’s not architecture anymore.”

That evening, the developers of his midtown tower have organized a party in his honor at MoMA, which proves to be an exercise in glittering idolatry. A huge mirrored sculpture of the skyscraper glows on a pedestal, a real-estate totem that I half-expect to start shooting jets of chilled vodka. Nouvel admires it a little blankly, then drifts out into the sculpture garden, trailed by a camera crew that records his every pleasantry. Two of his grizzled peers, Richard Meier and Steven Holl, are standing by to embrace him, and the three rival kings pose for photographs as if they were all on the same team. Slender people clutching slender flutes of bubbly swirl toward Nouvel on plumes of chatter, and he says little, eking out slightly crooked smiles. He catches my eye and shrugs. You see? he signals: This is what they put me through, all this luxe and volupté, when what I want is calme.

*This article appears in the June 29, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.