Gun massacres have grown into a depressingly familiar public ritual of shock, tragedy, and then, ultimately, a return to normality undisturbed by a policy response. The Charleston massacre has produced something different and unexpected: not momentum for gun control, but a widespread reevaluation of publicly sanctioned displays of the Confederate flag. The reconsideration of the Stars and Bars runs wide and deep, ranging from Walmart (a retailer shedding its identification with red America) to the governor of Alabama. The movement against Confederate symbolism encompasses a mix of business logic — an association with backward thinking prevents states for competing for economic talent — to apparently heartfelt realizations, like this moving statement from South Carolina Representative Mick Mulvaney. (“I blame myself for not listening closely enough to people who see the flag differently than I do. It is a poor reflection on me that it took the violent death of my former desk mate in the SC Senate, and eight others of the best the Charleston community had to offer, to open my eyes to that.”)

Some quarters of the right have greeted the sudden retreat with indignation and fear. Weekly Standard editor William Kristol decried liberals for “expunging every trace of respect, recognition or acknowledgment of Americans who fought for the Confederacy,” a spectacle he called “our own mini-French Revolution, expunging history in a frenzy of self-righteousness.” Rush Limbaugh predicts, “The next flag that will come under assault, and it will not be long, is the American flag.”

It might seem bizarre to equate patriotism with treason, and to conclude that turning against the symbols of an army that went to war against the United States must lead to turning against the symbols of the United States itself. There is, however, a certain logic to this fear — a twisted logic, to be sure, but twisted by decades of propaganda.

The story of the Civil War is that the United States won the war but lost the occupation. Union soldiers occupied the South and attempted to rebuild a colorblind democracy, an effort called Reconstruction. The Confederate forces eventually reconstituted themselves as an non-uniformed guerilla army that could melt invisibly into the civilian population and launch strikes to defeat the occupying army and terrorize its allies — freed blacks and sympathetic white Republicans. Eventually, the white North gave up and allowed white Southerners to disenfranchise African-Americans and reimpose white supremacy while stopping short of full enslavement. The reconciliation between whites of the North and South formed the basis for the country’s self-conception. The veneration of treason did, in its strange way, support a patriotic idea — an idea of a country after a brief and tragic misunderstanding.

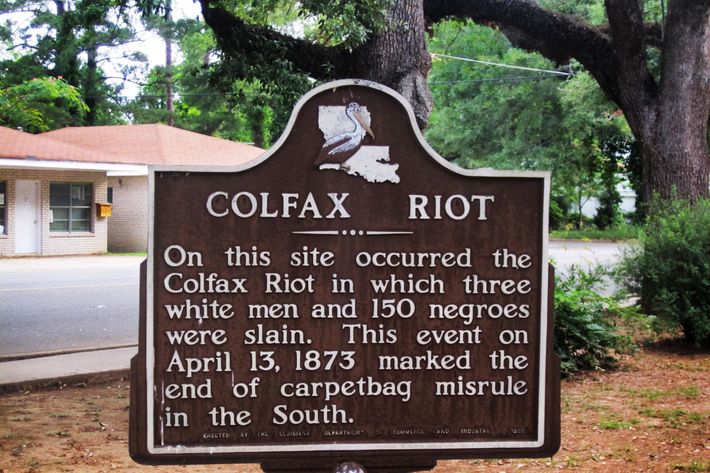

The winners write the history books, and — having defeated the postwar occupation — the newly victorious South set about falsifying the history of the period. It defined Reconstruction as the “misrule” by “carpetbaggers.” The entire country emphasized reconciliation between whites of the North and South, presenting the conflict as regrettable and perhaps unnecessary. The leaders of the Confederacy have been memorialized as heroes, their names adorning roads and schools throughout the South. The thousands of victims of white domestic terrorism, by contrast, have gone almost completely unacknowledged.

One small example stands for the larger phenomenon. In Colfax, Louisiana, white terrorists massacred dozens of freed African-Americans, deposed their democratically elected town government, and reimposed a whites-only government. The site of the massacre is currently memorialized by this sign:

In 2003, an Atlantic correspondent traveled to Colfax and was so unfamiliar with the actual events of 1873 he sought to piece together the history from locals and bare forensic evidence. More recent histories have uncovered the macabre events, which reflect the methods employed across the South.

Those conservatives alarmed at the current backlash against the Confederate flag are probably correct that it will not stop at the flag itself. What’s wrong is their interpretation of what this means. South Carolina State Senator Lee Bright, the state co-chair for Ted Cruz’s presidential campaign, has called the flag backlash a “Stalinist purge,” telling Politico, “They want to take down the Confederate monuments; I’ve gotten emails from people who want to rename streets. … Anytime you want to basically remove the symbols of history from a state, that’s something that just is very bad.” The closest approximation of a Stalinist purge — the brazen rewriting of history to suit modern political ends — took place decades ago. The current movement is, if anything, a de-Stalinization.

The trembling conservatives are also not irrational in their fear that the backlash against the Confederate flag could metastasize into a backlash against America. Neo-confederate revisionism is a form of patriotism. And many atrocities have indeed been committed under the colors of the American flag. As Limbaugh says, “Can you just hear it now? I can hear it now. ‘The United States flag has flown over slavery and symbolized racism, discrimination, bigotry, homophobia for hundreds of years; the Confederate flag flew only four years, and we’re getting rid of the Confederate flag.’”

That may be an apt description of the analysis on some parts of the left, the parts that treat oppression as intrinsic to America. But it runs distinctly contrary to the analysis proposed by President Obama, who is the main spokesman for American liberalism today.

Obama has proposed a different kind of patriotic story. He has refined versions of that story throughout his career, perhaps most famously at his star-making 2004 Democratic National Convention keynote speech. As Greg Jaffe recently reported, Obama considers his March speech in Selma, Alabama, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge its most articulate and fully developed version. In that speech, Obama called the march “a contest to determine the true meaning of America,” and declared that “the idea of a just America and a fair America, an inclusive America, and a generous America — that idea ultimately triumphed.”

The message of Obama’s Selma address was not complacency. Rather, he placed the struggle to expand freedom and opportunity to all at the center of American history. Unlike the post–Civil War revisionism, which writes the Confederates into the narrative of American greatness, Obama writes them out, or casts them as obstacles inevitably defeated (the civil-rights movement having won a century later what the occupying Union army had lost). Obama instead placed the African-American struggle for equality as the center of the struggle for social justice, and the struggle for social justice at the center of what America means:

That’s why Selma is not some outlier in the American experience. That’s why it’s not a museum or a static monument to behold from a distance. It is instead the manifestation of a creed written into our founding documents: “We the People…in order to form a more perfect union.” “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

This is a form of patriotism, but a very different kind than that with which many Americans have been reared.