Actual bipartisanship is breaking out in Congress. Last week, the House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly to increase spending on medical research. Meanwhile, the Senate is coalescing around a bipartisan plan that would finance infrastructure spending through tax reform. The good news is that Congress is figuring out ways to prevent its fiscal deadlock from stopping the kinds of domestic spending that everybody agrees on. The bad news is that the rules they have to follow to get this done are absurd.

The Republican Congress follows certain budgetary principles that have been in place long enough that they have faded into the backdrop of the political debate and are not the subject of open debate, or even acknowledgement, but taken as a given. The rules hold that if Congress votes to cut taxes or to increase military spending, it can disregard the costs. (Though military-spending hikes have to be added year by year, to preserve some accounting fiction that they are not permanent.) Domestic spending, on the other hand, can only be increased if Congress “pays for it” with offsetting measures.

Obviously, this makes it extremely hard to increase domestic spending. Republicans oppose tax increases for any reason at all, because, as Grover Norquist has taught them, raising taxes even a tiny amount makes the baby Reagan cry. In theory, they like cutting spending, but in practice, the only spending programs they actually specify for reductions are the ones aimed at poor people, which Democrats don’t like to cut, creating a stalemate.

The problem for Republicans is that there are some domestic programs they not only don’t want to cut but prefer to expand. The inability to maintain transportation infrastructure has created huge problems for business, which has been lobbying for years to fix it. The Highway Trust Fund is the traditional mechanism for financing interstate highways. The traditional way to keep revenues in balance with expenditures is to increase the gasoline tax periodically. But that violates Republican religion.

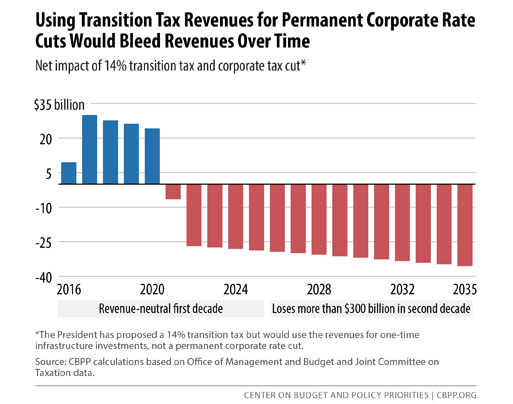

So the bipartisan solution is to reform the international business tax, create a big onetime tax cut for companies that bring overseas profits home, and then use the windfall to finance roads. This plan would increase revenue in the short-run, then create a permanent long-term drain:

But since Washington’s budget rules only cover the first decade, it scores as a tax increase.

Likewise, Republicans are actually pretty fond of medical research. As Republican Fred Upton put it, “Every family is impacted by disease; they just are,” Mr. Upton said. “My wife has lupus, my dad has diabetes, my mom’s a cancer survivor. And I’m no different than anyone else.” Conservative Republicans are happy to slash food stamps or Medicaid because there’s no chance they or anybody they care about will rely on those programs. But even rich people can get a terrible disease.

So they want to fund the National Institutes of Health. Since Republicans can’t use taxes to finance government outlays they want to increase, they need something else.

Their plan is to sell off parts of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The S.P.R. is a huge store of oil owned by the federal government that safeguards the economy against a sudden disruption in the oil supply, and it can also be used to cushion against price spikes by selling supplies into the market when prices rise and buying up reserves when it falls. Whether or not it makes sense to maintain the Strategic Petroleum Reserve — I think it does — selling it off to finance an ongoing expense has no fiscal logic.

But these are the traps Congress finds itself in when it attempts to reconcile practical recognition of the need for government with rules designed to prevent pragmatism in any form. It’s possible to find temporary workarounds rather than confront the irrationality of the Republican anti-tax religion. But there are only so many gimmicks and they only last so long. What’s going to happen the next time Congress needs to support research or finance some roads?