In the ESPN solar system, the network’s Bristol, Connecticut, headquarters is the sun, which makes its Los Angeles office something like Pluto — many miles away, and its status as a planet recently up for debate. In early May, ESPN parted ways not-quite-amicably with Bill Simmons, who founded Grantland, the pop culture and sports site based out of L.A. That office is also home to the Undefeated, a not-yet-launched site meant to explore race, culture, and sports. In 2013, John Skipper, ESPN’s president, hired Jason Whitlock, a prominent and controversial sports columnist, to launch the site. Whitlock agreed, and, in a moment he would come to regret, went on Simmons’s podcast and declared that the site would be, for lack of a better descriptor, a “Black Grantland.”

It took only hours for a mock “Black Grantland” Twitter account to be created — “Our articles are 3/5ths shorter!” — but nearly two years later, the actual site still doesn’t exist. It was supposed to launch in August 2014, February 2015, sometime this May, and, most recently, June 24. In late April, as explanation, Deadspin ran a 10,000-word story titled “How Jason Whitlock is Poisoning ESPN’s ‘Black Grantland,’” which detailed Whitlock’s difficulty attracting talent to the site, and the striking dysfunctions in his management of those who had joined it.

On May 26, Skipper visited the Undefeated office to check up on the site. I was supposed to go to L.A. that week, too, after ESPN and Whitlock agreed to a profile of Whitlock and his site. I was to join Whitlock at an annual Memorial Day barbecue at his mother’s house, in Indianapolis, then fly on to Los Angeles, to visit the Undefeated’s office. My flights were booked when Whitlock called from an unknown number 12 hours before my departure. Half an hour later, he had uninvited me from both trips for reasons that were off the record, but did little to convince me that others I spoke to who have worked and interacted with him, at ESPN and elsewhere, were being overly harsh in describing him as paranoid, dismissive of young writers, and difficult to work with.

Perhaps Whitlock simply saw the writing on the wall: Three weeks after that call, Skipper removed Whitlock from the site he’d been hired to create, before that site had even launched. It’s difficult to say exactly why ESPN let Whitlock go. (Both sides declined to comment on the record for this story.) The Deadspin article was read throughout Bristol, but several people at the company said the problems had been well-known for some time. ESPN has so far insisted that both of its L.A. outposts have bright futures, though the trajectories of both are less clear without their founders at the helm. The Undefeated’s aborted lift-off is instructive in understanding both the difficulty of the task at hand — a massive sports media organization creating a website examining the most pressing social issue of the day — and the precarious position of such “affinity sites,” including Grantland and Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, in the ESPN universe.

Though Whitlock is no longer in charge, the Undefeated’s future can’t be assessed without understanding its founder, whom Skipper had personally selected to build his latest prestige project. A former college football player, Whitlock worked his way up the newspaper chain until landing a coveted job in 1994, at 27, as a sports columnist for the Kansas City Star, where I grew up reading his columns. I recently took a dive back into Whitlock’s archive, which confirmed my recollection: He was a damn good columnist — sharp, clever, and provocative, lobbing Molotov cocktails into Arrowhead Stadium and Allen Fieldhouse. “I’m a bit of a rabble-rouser,” he wrote by way of introduction in his first column. (He was also fun: Whitlock once promised that if my high school beat a rival in football, he would show up at a pep rally dressed as a cheerleader. He did.) Even then, his columns routinely ventured beyond the field, particularly into issues of race, and he earned the columnist’s ultimate sign of respect: You might not agree with him, but you were certainly going to read him.

In the early 2000s, Whitlock started writing for ESPN, and his reputation for a particular kind of outspokenness began to develop a national following. In 2007, after Don Imus referred to members of the Rutgers basketball team as “nappy headed hos,” the ensuing debate generally settled into two camps: those who thought Imus should be fired, and those who defended him on First Amendment grounds. Whitlock found a different lane, asserting that black Americans only had themselves to blame for Imus’s words:

Thank you, Don Imus. You extended Black History Month to April, and we can once again wallow in victimhood, protest like it’s 1965 and delude ourselves into believing that fixing your hatred is more necessary than eradicating our self-hatred.

While we’re fixated on a bad joke cracked by an irrelevant, bad shock jock, I’m sure at least one of the marvelous young women on the Rutgers basketball team is somewhere snapping her fingers to the beat of 50 Cent’s or Snoop Dogg’s latest ode glorifying nappy-headed pimps and hos.

I ain’t saying Jesse, Al and Vivian are gold-diggas, but they don’t have the heart to mount a legitimate campaign against the real black-folk killas.

It is us. At this time, we are our own worst enemies.

The column earned Whitlock appearances on the Today show, Oprah, and Tucker Carlson’s MSNBC show, where he told the host, “Black people have a new set of problems and we need some new leadership.” Carlson replied: “I nominate you, Jason Whitlock.”

The appearances helped establish Whitlock as a standard-bearer for respectability politics — the belief that minority groups can improve their economic and social realities by policing the behavior of their peers to better fit mainstream society — and a reputation as the sports world’s Bill Cosby. Respectability politics traces its roots to Booker T. Washington and still has advocates — even President Obama has occasionally trafficked in it — but most young black intellectuals, including many of the kind Whitlock tried to hire for his site, have largely discarded it. “Respectability politics is, at its root, the inability to look into the cold dark void of history,” Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote last year, in an essay about Charles Barkley, Whitlock’s primary competition for the Cosby role. “If aliens were to compare the socioeconomic realities of the black community with the history of their treatment in this country, they would not be mystified.” Whitlock, meanwhile, campaigned endlessly against the N-word and the degrading effects of hip-hop culture. (He has more recently added mass incarceration to his list of campaigns, after reading Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow.) One name Whitlock considered for his site was “Twice As Hard,” from the black proverb: “You’ve got to work twice as hard to get half as far as a black person in white America.” Whitlock’s basic cultural analysis has long been that rap music was making it thrice as hard.

Whitlock became “the racist right’s unwitting attack dog, here to explain how black people were the problem,” as Greg Howard put it in Deadspin, a position that did little to ingratiate himself to many younger African-Americans. “In the same way that people complain about the good old boys club that run America, we have a good old boys problem with old black men who are angry that there’s no longer a singular voice for black people,” Sal Masekela, a former ESPN host who now does sports stories for Vice’s HBO series, told me. “They take this approach to demeaning the successes in a different direction of young black men who’ve had to struggle just as bad as they did just because it’s a different struggle, and one they don’t identify with.”

Whitlock, though, received enough support to know he wasn’t alone. Mike Wilbon, one of ESPN’s most prominent black commentators, didn’t agree with Whitlock on every issue, but made him a regular co-host on his debate show, Pardon the Interruption. “Jason’s black social conservatism was actually what attracted me to him,” Christopher Scott, a 34-year-old black marketing specialist in Las Vegas, told me. Though the Undefeated has been presented as an idea that originated solely in the brain of John Skipper, Scott says that even before ESPN approached Whitlock, he had been helping Whitlock formulate a proposal for a site much like the Undefeated that Whitlock planned to pitch to Fox Sports. (Whitlock was fired from ESPN in 2006, after criticizing several of his colleagues, including Scoop Jackson, another black columnist, whom he accused of “fake ghetto posturing” and “bojangling for dollars.”) “Jason had this idea for a sort of all-encompassing, hip-hop culture, race, social, type of site,” Scott said. According to Scott, the site was to be called “Red, White, and Truth,” the same name given to a TV show Whitlock was developing for Fox Sports 1.

The Undefeated also wasn’t ESPN’s first attempt to specifically target African-Americans. In 2003, it aired Block Party, a show about “sports in context with the emerging urban youth culture,” hosted by Mos Def, and in 2012, a year before hiring Whitlock, Skipper gave funding to Keith Clinkscales, a black ESPN executive, to help run a website called the Shadow League that would cover largely the same space: topics on its homepage range from fashion at the NBA Draft to the Confederate flag to Misty Copeland becoming the first black principal dancer at the American Ballet Theater.

ESPN and the Shadow League eventually cut ties, and Skipper approached Whitlock, who was arguably the most well-known black sports columnist in the country. Grantland had proven itself an editorial success, and a month before Whitlock’s hiring, Skipper had pulled Nate Silver from the Times. (Whitlock’s poaching from Fox also came not long after News Corp. announced it would be creating Fox Sports 1, which was being positioned as the most credible challenge to ESPN’s cable sports supremacy.) As explanation for Whitlock’s hiring in the face of his reputation and prior flame-out at ESPN, Skipper pointed to Whitlock’s willingness “to take unpopular stands, to challenge the perceived wisdom of any community.”

When Grantland launched, it was mocked in certain corners, but practically every young, male writer from Echo Park to Cobble Hill was clawing to climb aboard. The Undefeated, which promised to hire a number of minority writers, should have caused equal fervor, if only for reasons of job-market expansion: Bill Russell, the Boston Celtics legend, once said that the only place in sports whiter than the front offices were the press boxes, and not much has changed. A 2012 study found that just 8 percent of sports journalists at newspapers and online publications were black, an especially stark number compared to the two thirds of NFL players and three fourths of the NBA who are black.

ESPN, to its credit, has a relatively good reputation for diversity. “They make the rest of the sports-journalism industry look good,” Ron Thomas, who runs a sports-journalism program funded by Spike Lee at Morehouse College, told me. “Because they hire such a high percentage of the black sports journalists and skew the numbers.” When Skipper was conceiving the Undefeated, he spoke to Bill Rhoden, a columnist at the Times, about getting students from historically black colleges involved in the site. If it ever gets off the ground, Thomas said, the plan is for students from Morgan State, Rhoden’s alma mater, and Morehouse to join as interns.

But many black journalists were less than excited about the Undefeated. “Jason’s a great columnist, and columnists are supposed to elicit response, move the needle, so he can say whatever he wants,” one black journalist at ESPN told me. “But at what point does that disqualify you as a guy who’s gonna run a website that’s all about connecting with an audience that you’ve offended so many times?” When Whitlock’s hiring was announced, a number of ESPN employees went to Skipper and other executives to express reservations about Whitlock. One black editor at a prominent digital publication — many black journalists declined to speak on the record, citing some variation of the fact that, “This is a very small world, and we all have to work in it for another 30 years” — told me he viewed the site the same way he looked at Tyler Perry’s movies: Employed black writers were better than unemployed ones, but the site under Whitlock only seemed likely to set back to the cause.

Whitlock’s relationship with the younger regions of the internet was not always so strained: In 2013, around the time Whitlock returned to ESPN, he invited the staff of Deadspin to dinner at Virgil’s, in Times Square, during which the staff presented him with a “Good Writering Award,” after Whitlock had complained that his columns weren’t eligible for a Pulitzer Prize. Everybody seemed in on the joke. I also spoke to several young black writers — mostly those at less prominent publications, or for whom sportswriting was a part-time passion — who rejected many of Whitlock’s views, but said they would have considered joining the site if Whitlock had asked. Christopher Scott, who says he worked with Whitlock on developing the site for Fox, insisted that, “Whitlock wasn’t out to push his agenda. He felt this could be a place where discussion could happen — the kind of discussions that came out of those salons in the Harlem Renaissance.”

Whitlock’s initial attempts to staff the site suggested as much, as he set about trying to hire everyone from traditional sports reporters to those who covered criminal justice. But he quickly found that many of his targets weren’t interested. Some were content in their jobs; others were hesitant about working for him. Resources were not a question — the site recently sent one of its reporters and a film crew to South Africa for a story on Josiah Thugwane, the country’s first black Olympic gold medalist — nor were salaries. Whitlock’s top target was Ta-Nehisi Coates, The Atlantic writer whose “The Case for Reparations” Whitlock held up as the standard to which he wanted his site to aspire. Whitlock offered to triple Coates’s salary, but Coates still turned him down. A friend of Coates’s said the idea of potentially running such a site would have appealed to Coates, but he had little interest in working for Whitlock.

Many potential hires said they weren’t convinced they would be able to report and write the types of stories they wanted, and some were concerned that working for Whitlock would put them on the wrong side of history. Whitlock’s response to the protests in Baltimore had been to tweet that “Children need committed parents. Gotta rebuild the home,” and a few days later, he linked to an article arguing that the string of young black men killed by police had been an overhyped story, because almost as many people were killed each year by lightning strikes and dogs. “A lot of us feel as if we’re writing things at a particular moment in history that people are going to look back on, so it’s extremely important that the tone and confection of these pieces are right,” one reporter who covers race told me. “Being the guy in 1960 saying Martin Luther King Jr. was not all he’s cracked up to be would have gotten you a lot of newspaper readers, but it’s not about getting clicks now. It’s ‘Are these going to hold up to the scrutiny of history?’”

Rebuffed by many of his top choices, who would have provided in-house sparring partners, Whitlock ended up with a staff populated in large part by people with similar perspectives to his own. Mike Wise, a white columnist from the Washington Post, shared Whitlock’s feelings about the N-word, and Brando Starkey, a Harvard Law graduate, had just written a book called In Defense of Uncle Tom: Why Blacks Must Police Racial Loyalty, which Whitlock blurbed. The fears of many who had rebuffed Whitlock were confirmed when Deadspin published tales of his apparent managerial ineptitude, along with the 47-page “playbook” Whitlock had distributed to employees as a guide to the site’s direction. It included 16 inspirational quotes from everyone from Maya Angelou to Mike Krzyzewski; seven of the quotes came from Jason Whitlock. “We will have causes,” he wrote. “We will take a position against use of the N-word, and write stories that hammer home these beliefs.” One writer I spoke to said he found the site’s “civilizing mission” particularly off-putting. “I brought this up with a friend,” he told me. “What if we want to do a Drake profile? Would they be like, ‘He says the N-word, so, no.’”

Prior to Whitlock’s firing, the Undefeated only published five articles, most notably a nearly 10,000-word attempt to position Charles Barkley as a modern day Booker T. Washington, which Whitlock told his staff in an email was “the greatest piece of sports journalism I’ve ever been associated with or seen (other than Taylor Branch’s piece on the NCAA amateurism).” Few others felt that way, partly on account of the strained historical analogy, but equally because the piece seemed overly long, poorly edited, and, well, boring.

In talking with a number of black journalists about where the Undefeated goes from here, that last criticism was one of the more common refrains. Part of what has made Grantland a largely admired site is its ever-present sense that the topic at hand — sports and culture — is not to be taken too seriously. There are moments for weightiness, but those stand out all the more because of the site’s general dedication to having fun with its subjects.

Covering race in a sophisticated way will occasionally require a different level of gravitas, but part of the Undefeated’s brief is to cover “urban culture,” a broad cultural category that includes much of what’s considered cool in American today, and goes well beyond examining blackness. “The idea to me that, in 2015, you’re making a place that’s gonna be mandating black culture doesn’t compute,” Masekela said. “There’s so many different ideas and definitions and lanes of blackness, of urban culture, and how it’s being celebrated by a lot of people who don’t necessarily wear the skin color. It should be a place that’s curating cool shit, and has a cool voice.” Whatever the Undefeated was to be under Whitlock, going forward it needs to feel like less of a lecture than the stories it has published thus far.

One recommendation — largely, it’s worth noting, from young people — was simply to bring in more young people. “They don’t have to have a master’s degree,” Robert Littal, who runs Black Sports Online, said. “That’s what you hire editors for. You need people who are in the streets.” By the streets, Littal meant the corner of (forgive me) Vine and Twitter Boulevards, where much of urban culture gathers. Several people I spoke to suggested that perhaps the best outcome for the Undefeated would be to merge with a site that already does a decent job covering the intersection of sports and culture in a fun and sophisticated way — a site like the one in the same building. “The best thing about Grantland from the beginning was that those guys have just a great command of what’s cool,” Masekela said.

For now, post-Whitlock, the Undefeated is being run by Leon Carter, a former Daily News sports editor whom ESPN had sent to L.A. as Whitlock’s No. 2. Many people who had expressed concern about Whitlock’s lack of experience as a manager spoke highly of Carter’s. ESPN had thus far given its affinity sites to writers, which had worked out in Simmons’s case — the verdict remains out on Silver — but it was possible that a site like the Undefeated, attempting to cover a more contentious space than pop culture or data crunching, might do best without a figurehead whose views would inevitably define perception of the site. “I don’t know if I would have gone to write for James Baldwin’s magazine, because then you would be the guy who worked for James Baldwin’s magazine,” one black writer told me.

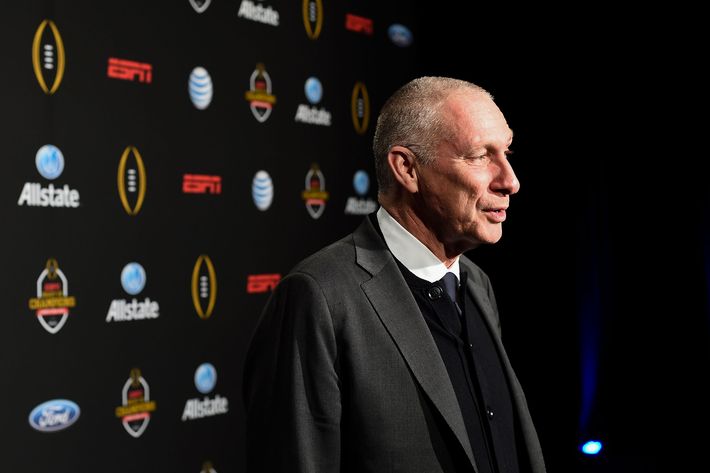

One reason for optimism about the site’s future is Skipper, who holds a master’s in English literature from Columbia and is almost universally admired within ESPN. The economic utility of Grantland, FiveThirtyEight, and the Undefeated is limited; their primary purpose is prestige, boosting the reputation of ESPN as a place where high-minded work can exist alongside debates about Tim Tebow. All three sites, along with “30 for 30,” the network’s acclaimed documentary series, exist under the umbrella of Exit 31, an ESPN division created last year “to focus on expanding creative storytelling beyond traditional content areas.” Multiple people at ESPN say Skipper, who is 59, is committed to the Undefeated, and to cementing ESPN as a vibrant place for sophisticated discussions of sports and culture.

Skipper has offered a plausible economic rationale for the Undefeated — “African-Americans believe ESPN is their TV network, but they are more ambivalent about ESPN.com as their site” — but a business argument for its existence is largely beside the point. ESPN spends money willingly and widely because it can, and for the same reason the company’s support for the ESPYs, its annual money-losing award show, was once explained to me as such: If ESPN doesn’t do the sports award show, Fox or Bleacher Report or someone else would.

At the same time, that impulse has more recently come into question. In May, Disney, ESPN’s parent company, reported better-than-expected quarterly profits, but unlike much of its recent history, ESPN wasn’t among the primary profit drivers. (Bob Iger has Frozen to thank instead.) Income dropped 2 percent in Disney’s media networks division, which includes ESPN, and Disney blamed the dip in part on production and programming costs at ESPN. That primarily means the billions ESPN has spent buying up the live broadcast rights for various sporting events, but it’s hard not to imagine a cost-conscious Bristol seeing a pair of embattled sites 3,000 miles away as cheap ways to cut back.

Whitlock, for his part, seems to have moved on: Two weeks after his firing, he appeared as a co-host on Pardon the Interruption, holding up a copy of “The Big Sexy Playbook.” (Whitlock’s nickname, “Big Sexy,” is a winking nod to his size.) The Undefeated, now approaching the two-year mark since its conception, doesn’t have so much as a speculative launch date. Several journalists who turned down offers to join the site under Whitlock said they might one day reconsider — though perhaps only after the site got its footing. The Undefeated’s future remains uncertain, but it’s useful to recall an article from The Atlantic, in 2011: “Bill Simmons’s Grantland Is Doomed Even Before Launching.” In hindsight, Grantland was far from doomed. Early warning signs aren’t necessarily a death sentence. But if the Undefeated is to succeed, those working on it will now have to work twice as hard to get there.