In an interview yesterday with the Union Leader, Jeb Bush committed an act of honesty. Asked to explain his economic program, Bush explained his goal of precipitating unprecedented economic growth, which, as he put it, “means we have to be a lot more productive, workforce participation has to rise from its all-time modern lows. It means that people need to work longer hours and, through their productivity, gain more income for their families.” Democratic groups are already emailing the comments to reporters. Bush’s comments may or may not develop into “gaffe,” depending on whether his advisors calculate the political fallout helps or harms their candidate. Far more interesting than the campaign dynamics, though, is the fact that Bush has introduced an important idea that reveals profound differences between the two parties.

One interesting tip-off from Bush’s comments is that he uses the concept of productivity to mean something different than its economic meaning. In economic terms, productivity means output per hours worked. That is a crucial concept for economists, because, over the long run, higher productivity is the only way a society can actually increase its standard of living. You can increase your societal wealth by increasing the amount of hours worked, up to a point, but there are only so many hours in the day. Americans enjoy higher levels of prosperity today than we did a century ago because we produce far more in the hours that we work. In his second sentence, and possibly his first as well (its meaning is more ambiguous), Bush uses productivity to mean producing more by working more — people need to work longer hours and, through their productivity, gain more income.

This casual slip in usage reveals an important assumption. Bush not only prefers higher productivity in its technical meaning (higher output per hours of work), which both conservative and liberal economists consider axiomatic; he likewise considers higher levels of work implicitly preferable. Liberals do not share that assumption. And the division over this question turns out to be buried within many of the economic fights of our time.

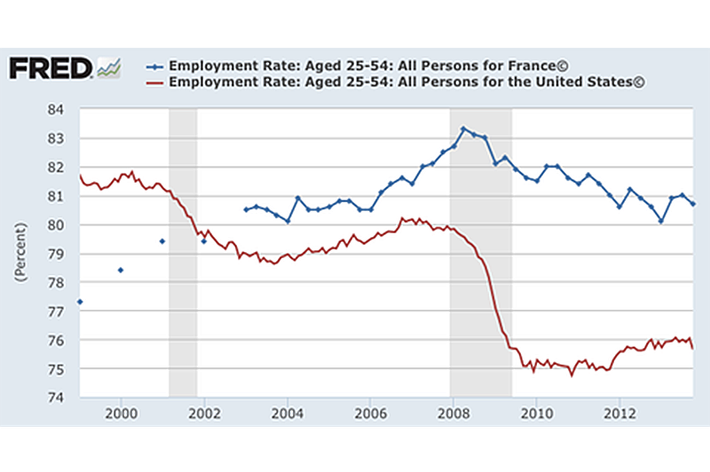

Conservatives like to contrast American-style capitalism with Western European sloth. But the difference does not lie in how many Americans work. As Paul Krugman has pointed out, among people ages 25 to 54, a higher percentage of French than Americans work full-time:

Output per working hour is also similar. The main difference is that Americans work many more hours than French workers, or workers anywhere in the advanced world except South Korea and Japan.

Conservatives embrace that distinction, and seek to extend it further still. A major economic rationale for tax cuts, aside from the underlying moral desire to allow the winners of the market economy to keep their money, is to coax more labor out of the workforce. When faced with the choice of working more hours or enjoying more leisure time, a higher tax rate tends to encourage more leisure. (If you get to keep three quarters of the extra dollar you earn, you might work that extra shift. If you only keep half, you might not.) Liberals have less interest in coaxing those additional hours out of the labor force.

The differing preference for more or less work also come out in different ways as well. Conservatives loudly trumpeted the Congressional Budget Office’s prediction that Obamacare would lead to fewer hours worked. Conservatives often described this as Obamacare “destroying jobs,” but that is not what the CBO actually concluded. It found, instead, that since many people hold onto full-time jobs in order to maintain their employer-sponsored insurance, providing them with affordable insurance outside their employer plan would lead some of them to retire, or work part-time. Liberals consider that result perfectly fine. If a person can afford to retire, or work part-time, or care for their children or an ailing family member, they’re better off doing so rather than having the need for employer insurance dictate their life. Conservatives disputed this conclusion, arguing that the decline of work is a serious societal problem.

Much of the dispute centers not on incentives but on whether workers should have the freedom to choose more leisure time. Democrats favor more generous family- and medical-leave policy — the downside of which is, of course, less work. In Wisconsin, Republicans are proposing to eliminate a state law granting workers the right to one day off every week. In theory, the choice to work a seven-day week is a mutual decision between employer and employee. In practice, the boss has most of the leverage, and employers who want their employees to work seven days a week will get rid of workers who don’t.

Opposition to laws and customs that enforce periods of rest, and a culture where workers can comfortably balance their jobs against family life and leisure, sets American conservatives apart from American liberals and the rest of the Western world. They are not wrong in their belief that more work buys us more income. What Jeb Bush and his party assume about this trade-off is very much an open question: Would more work actually make Americans happier?