If These Girls Knew That Slender Man Was a Fantasy, Why Did They Want to Kill Their Friend for Him?

The problem wasn’t that they didn’t know they were living in a fantasy world. The problem was that they couldn’t — or didn’t — extricate themselves.

Payton had been called “Bella” since about the first grade. Morgan had been Bella’s best friend since fourth. Both girls loved cats and playing dress-up. Morgan was obsessed with Harry Potter; at least one time at lunch, she and Bella imagined that Voldemort was pursuing them through the cafeteria. Now in sixth grade, they talked on the telephone every night. Morgan’s favorite teacher was Jill Weidenbaum, for reading and writing, and on May 30, 2014, the Friday of Morgan’s 12th-birthday sleepover, both girls hung around Ms. Weidenbaum’s classroom after school, helping her clean up.

There were three girls at the sleepover at Morgan’s house that night: Morgan and Bella and Morgan’s newer friend Anissa, who lived in the same housing complex as Morgan — Sunset Apartments, on Big Bend Road — and rode the school bus with her every day. Anissa and Bella knew each other, but Morgan was what they had in common: Each would have said that Morgan was her closest friend. At school, Anissa was an outsider, and Morgan a fantasist who made up stories in her head. Bella was the most social of the three; she had a reputation as a pleaser. But as a group, these were not the most popular girls at Horning Middle School. One Horning mother called them “misfits” — not “girly girls,” maybe a little immature. They were not much interested in boys, or bands, or in trying out for the prizewinning Waukesha Xtreme Dance Team.

Waukesha is a suburb of Milwaukee, a politically conservative and fairly bleak place, despite its spot on a few “best places to live” lists. Sunset Apartments, on the wrong side of Sunset Drive, consists of 72 units in neat but drab two-story subsidized housing where backyards are fenced and small curtained windows and closed doors look over a parking lot. The rather desolate downtown is marked by endlessly passing freight trains and a biker bar or two, but unless kids play sports, and lots of them do, there are not many obvious gathering places where they can meet.

But there is Skateland — an indoor roller rink, especially popular on Friday nights, where a DJ plays Top-40 hits and a constellation of disco balls lights the floor; the green-and-purple picnic tables are sticky with spilled Coke. That Friday, Morgan, Bella, and Anissa headed there around dinnertime — chauffeured by Morgan’s father, Matt — and stayed until about 9:30, when Morgan said she wanted to leave. Back at Morgan’s, the girls goofed around on their laptops until they eventually settled down together in Morgan’s loft bed, Anissa and Morgan side by side and Bella horizontal along the head. Later, Anissa remembered that Bella accidentally kicked her in the face and that, in retaliation, she kicked back.

The next morning, someone had the bright idea of crushing granola bars into Silly Putty and flinging the mess at the ceiling, which they did, then worried over how to get it down. Then they played dress-up, each girl acting out her own avatar: Morgan as Data from Star Trek: the Next Generation; Bella as a princess in pink; and Anissa as a “prosti-troll,” a character of her own creation and “sort of inappropriate,” Morgan commented later. There were doughnuts and strawberries for breakfast, then Morgan asked her mom if they could go outside and play.

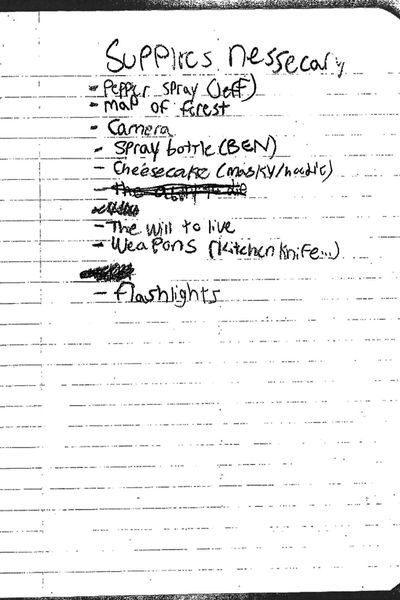

As the girls set out for David’s Park, Bella walked ahead and Morgan and Anissa lagged behind. It was then that Morgan pulled up the left side of her white-and-black plaid jacket to show Anissa what she’d taken from her kitchen — a thin knife, the kind you’d use for cutting vegetables or steak, Anissa said, with a black handle and a gray stripe. Anissa and Morgan gave each other sidelong glances. “I thought, Dear God, this is really happening,” Anissa later told police, all the months of fantasizing coming down to this day.

David’s Park is a green, grassy field about the size of a city block, with public restrooms for men and women at its northeastern edge; it was inside this dingy outpost that Anissa and Morgan first attacked Bella. There was a tussle in which Morgan tried to restrain Bella, and another moment when Anissa halfheartedly pushed Bella’s head against the brick wall. But Morgan fell apart just then, pacing and singing, and Anissa, the big-sister type, sent Bella outside to play while she comforted Morgan, petting her, she said later, like a cat. It was Anissa’s idea to go play hide-and-seek in the woods that form the far boundary of the park. Once Morgan was calm, the three girls headed there.

It’s hard to understand Bella’s decision to stick with her friends, why, after having been assaulted by them in the bathroom, she thought hide-and-seek might be a fun thing to do (though she might have interpreted the bathroom attack as just a mean episode of imaginary play — and it’s possible that, at the time, Anissa and Morgan saw it that way, too). Together they proceeded to the end of Big Bend Road, where the asphalt turns to gravel and dead-ends by the woods. These are suburban-type woods, not the state-park variety, scrubby and weedy and thick with brush. The Les Paul Parkway and a Walmart are just on the other side, less than a mile away.

Hide-and-seek was a haphazard affair. Morgan counted first, and Anissa and Bella hid. Anissa tried to tackle Bella, but couldn’t hold her down. It was then that Morgan gave Anissa the knife, but Anissa handed it back, saying she was too squeamish. While they talked, Bella was crouched down in the dirt, playing with flowers.

“I’m not going to until you tell me to,” Morgan said.

Anissa says she started to walk away, and when she had gone about five feet, she stopped. “Kitty now,” she said. “Go ballistic, go crazy.”

Anissa heard Morgan say, “Don’t be afraid, I’m only a little kitty cat.” Then Morgan pushed Bella over and stabbed her 19 times, in her arms and legs but also puncturing her stomach, her liver, and her pancreas and barely missing a major artery near her heart. “Stabby stab stab stab” is how Morgan recalled it. “It didn’t feel like anything,” she said during her interview with police, making a vague, loose stabbing gesture with her left hand. “It was, like, air.” Bella screamed and screamed: “I hate you! I trusted you!” She tried to get up and walk. She wobbled, though, and that’s when Anissa took her by the arm and steered her deeper into the woods and told her to lie down. Morgan tried to dress Bella’s wounds with a leaf, and then they fled, washing up in the sinks in the Walmart bathroom and filling their water bottles there. Then they wandered around Waukesha for a couple of hours, crying and singing and wilting in the heat, until they were picked up by police as they sat in the grass near an entrance to the interstate.

“Where’s Bella’s body now?” Anissa asked later that afternoon, two and a half hours into her interview with police. Bella was alive, the female detective gently told the girl. According to the complaint filed by the Waukesha County prosecutor’s office, Bella had crawled into the road. She was discovered by a passing cyclist and taken to the hospital, and had enough time, before the anesthesia took effect, to tell police what had happened. Anissa had been crying for most of the interview, but now relief, and something like serenity, washed over her face. “Will I be able to go back to school?” she asked. Since the third grade, she hadn’t missed a day.

Over the past year, the attack in Waukesha has come to be known as “the Slender Man stabbing.” This is because, during their interviews with police that Saturday, Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser, who at the time were both 12 years old, said they were trying to kill Payton Leutner to please a mythical internet horror creature named Slender Man — a tall, thin, faceless man in a suit who has tentacles growing out of his back and preys on children. The idea, Anissa carefully explained to the detective, as if giving a book report, was to become proxies, or puppets, of Slender Man through murder — an initiation ritual requiring a blood sacrifice. Anissa and Morgan told officers that, according to this logic, Bella’s death would earn them Slender’s protection. Afterward, they said, they would go to live with him in a mansion in the forest, morphing somehow into mini-monsters, not unlike the way humans who’ve been bitten by vampires are said to become vampires themselves.

The girls were charged with attempted murder in the first degree — as adults, in accordance with Wisconsin law — and have been held for the past 14 months in a juvenile-detention facility in Washington County, about 30 miles from Waukesha, as their lawyers have attempted to convince the court that they should be tried as juveniles. That effort failed earlier this month when, on August 10, Judge Michael Bohren, citing the particularly vicious nature of the crime, ruled to maintain their status as adults. One of the results of this decision is that their court files remain open, and because the girls’ lawyers declined interview requests, it is from these files, which include transcripts of hearings, exhibits, and hours of their videotaped interrogations, that this account is largely built. Many girls live in dreamworlds, but seldom are those worlds so thoroughly catalogued. The material is heart-stopping.

Slender Man was the most powerful and compelling of the characters that preoccupied Anissa and Morgan, but he was by no means the only one. Each girl was, differently, obsessed with a pantheon of imaginary creatures, and their friendship was built, in part, on a mutual love for tales of demons and supernatural evil. Morgan, in particular, had a rich fantasy life. Voldemort and Snape, villains from the Harry Potter series, were especially vivid to her; Voldemort she called “Voldie,” as if he were her pet. She regarded Spock, Star Trek’s Vulcan, as a mentor of sorts, a tutor in how to suppress emotion (one sign, perhaps, that she was aware of the extent to which her outward behavior was in need of editing). On the Facebook-page support group for Morgan, one photograph shows her wearing Spock ears; another shows her wearing a black hoodie emblazoned with the white bones of a human skeleton. Her favorite fashion accessory was a pair of black lace fingerless gloves, which she wore all the time, including during the attack (and which she left on the sink in Walmart, to her lasting regret). But all these gothic, fantastical impulses existed alongside the utterly unremarkable interests of a 12-year-old girl. A catalogue of the contents of her bedroom, made after the attack, includes her school backpack, which on that Saturday afternoon contained five volumes from The Littles series, famous children’s books about tiny people with tails who live in a human house. Also on that list: volumes of Mad Libs, the blanks filled in with a tween’s pornographic and scatological sensibility: penis, pooping, urine, horny, crapping, and “vajayjay.”

Bella, for her part, frequently went to school dressed up as a cat. According to the mother of a child who was friendly with her, she often drew whiskers on the backs of her hands; after the attack, some of the sixth-grade girls at Horning had the idea of going to school with whiskers painted on their cheeks in tribute to her, but the school nixed the idea. What the sixth-grade girls at Horning probably didn’t know was that Morgan liked to imagine herself as a cat as well — the predatory kind. “She said she was going to draw whiskers on her face if she became a proxy,” Anissa told police. “Don’t be afraid, I’m only a little kitty cat” would be her calling card, her “catchphrase.” In their real lives, both Bella and Morgan kept cats as pets and treasured them.

Adults expect a certain amount of fantasy play from children, and for tweens, it can be a useful, if not always healthy, way to cope. Pretending can offer a welcome regression into childhood. It can feed creative urges or provide an escape from stress. Fantasizing can also give an episodic sense of control over one’s environment, an effect that may have a narcotic appeal to those just starting to come to terms with their newfound agency in the world, and the fact that that agency has limits. It seems notable that Anissa and Morgan, with one foot still in childhood, fantasized about becoming only proxies of Slender Man, and not, say, vanquishing him: Even as they rejected the constraints of their world, their dream was one of submission to a supernatural authority, not independence.

By the age of 8 — and definitely by 12 — psychologists agree, most children are as able as adults to sort out what’s real from what is not. What sets children and adolescents apart from adults is a mental task psychologists call “discounting” — the rational inner voices that can subdue overheated emotional responses to the imagination’s powerful projections and that come with the maturing of the frontal lobe by around age 25. That’s why a 50-year-old can finish rinsing her hair even as she recalls the shower scene from “Psycho,” while a 16-year-old will find herself with a racing heart, soapy and dripping on the mat. But the feeling of being in the thrall of a fantasy (even a morbid one) can be seductive as well, as comforting as getting high, as mesmerizing as Minecraft.

In this way, the friendship of Anissa and Morgan, with its shared obsessions and mutually satisfying imaginary play, was the rather unremarkable effort of two bright, alienated kids to build a world more thrilling than their reality, a private bubble that offered them belonging, excitement, and a sense of their own power. The problem wasn’t that Morgan and Anissa didn’t know they were living in a fantasy world: Ultimately, when pressed by adults, they acknowledged the difference between fantasy and reality. The problem was that they couldn’t — or didn’t — extricate themselves from the fantasy. “He does not exist,” Anissa told police on the day of the stabbing. “He is a work of fiction.” Morgan, the more troubled one, had a more enduring attachment to the fairy tale they had told themselves and that had brought them to the woods. But even she admitted, in her interview, that the attack on Bella was “probably wrong,” she said. “I honestly don’t know why we did this.”

Anissa says she introduced Morgan to Slender Man around October 2013. At the time, all three girls were in their first year at a new middle school; Anissa and Morgan were socially isolated, but Bella was “a social butterfly,” according to those who knew her. In her interview, Morgan acknowledged Bella’s role as her social lifeline: “She was my only friend for a long time.” Even so, she said she found her “gullible.”

Teachers regarded Morgan as odd; she referred to herself as “creepy,” and in one of the notes found in her room she describes herself as a “mental case.” In the time since her arrest, she has been examined by a number of psychiatrists and psychologists, who have concluded that she is mentally ill, likely schizophrenic — an extremely rare diagnosis for a 12-year-old. And though none of the experts who have testified on her behalf in hearings have found evidence of “malingering” (the term psychologists use for “faking it”), there are those in town who wonder if there isn’t a theatrical aspect to her strangeness as well. During a court hearing in June, Jill Weidenbaum, the teacher, testified that Morgan sometimes engaged in inappropriate, attention-seeking behavior: She would bark like a dog or catch insects and fling them at classmates. In sixth grade, Weidenbaum was concerned enough to talk to Morgan’s mother. In January, Morgan was briefly suspended for bringing a hammer to school. But compared to the kind of misbehavior familiar to middle-school administrators, Morgan’s eccentricities seemed benign. She had an above-average IQ. Her grades were fine. She was responsive, curious, and a gifted artist. Sometimes she doodled or appeared distracted, but she did her homework on time.

Morgan’s parents have an erratic pattern of employment. Her mother Angie was laid off last November from her job at a hospital; Matt receives government assistance for mental illness. When he was a teenager, he was hospitalized for something like a schizophrenic break himself. Morgan’s dark imagination can seem disconcerting, but to tour the Facebook pages of both girls’ parents is to find oneself immersed in metal music and fairy paintings, and Morgan’s home seems to have had an especially gothic flavor. One of her father’s alleged email usernames was “ILOVEEVIL,” at least according to the English newspaper the Daily Mail; his Instagram handle was Deadboy420, and on that feed he posted (along with family pictures) brass knuckles tipped with skulls and a skull-and-crossbones birthday card he’d sent his wife. Just two months before the stabbing, Matt proudly posted a drawing Morgan made of Slender Man: “Only Mogo draws Slenderman in crayon on a napkin when we are out to dinner.”

Morgan and Anissa met at the school-bus stop, and their friendship blossomed on the ride to and from school. The previous year, Anissa’s parents had gotten divorced, and she was still reeling and feeling depressed. Her extended family is large, and her relationships with the adults in her life — with her father, especially — had been sustaining; she was having a hard time adjusting to the ruptures in her world. Anissa’s mother, Kristi, worked the night shift, Anissa told police, and would pick her up at the bus stop after school and keep her until William, Anissa’s father, came to get her after work. Psychologists who have testified on Anissa’s behalf say her parents are well-meaning but had no idea what kind of trouble she was in.

Morgan could almost seem bullying in her weirdness; Anissa is “thin-skinned,” says someone who has met her. She once slapped a classmate for using a racial epithet. Morgan’s over-the-top creativity must have appealed to Anissa, but perhaps she also saw in Morgan a vulnerability that gave her a sense of purpose. “I stand up for her every now and then because Morgan’s, like, a prime target for bullies at school,” she told police. “One time [a boy] got too close to Morgan, and I kind of didn’t like it, so I punched him kinda hard. He kind of started crying.” In the very first moments of her interview, before she began recounting the events of the day, Anissa warned the detective about Morgan’s oddities, like a worried mother giving fair warning to a child’s new teacher: “She can be a little dopey and forget what she’s saying, in the middle of a sentence, a lot,” she said. “Because, like, she says she hears voices, too.”

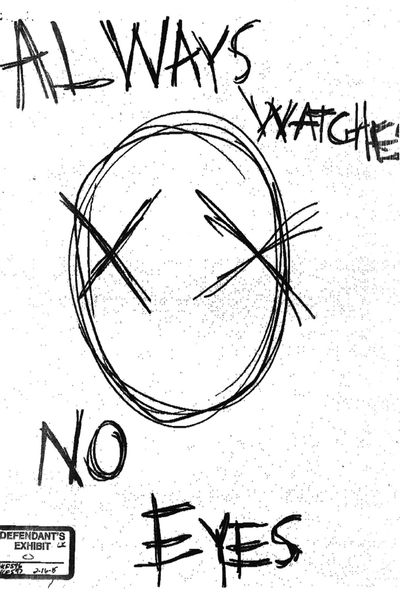

Anissa told police she first encountered Slender Man as a secondary character in a Minecraft video. A friend pointed her to Creepypasta, a collection of user-generated horror fan sites in which written, Photoshopped, and videotaped accounts of encounters with monsters and supernatural evil are presented as “real” in the form of encyclopedia entries, testimonials, and other “documentary” evidence. There, Anissa was drawn to Slender Man, but also to Zalgo, a super-evil entity, and to Jeff the Killer, an ever-smiling ghoul said to be based on an actual child murderer. It was Jeff’s “realness” — the “news accounts” on Creepypasta establishing his bona fides — that made her think that Slender Man might really exist. “We got our hopes up,” she told police. According to the mythology, Slender Man is a lurker. “He’s everywhere,” Morgan told police. He is almost always depicted around children, though whether he is merely observing the misfortunes that befall them or causing them to happen can be unclear. Some legends say he’s an abductor or a kidnapper; others say he disembowels his victims. Slender Man can invade one’s thoughts and can cause “Slender Sickness” (nausea and coughing up blood), insanity, and Scribbling In, an incessant compulsion to draw and write. In Morgan’s bedroom, in addition to Mad Libs, investigators found more than 50 drawings referring explicitly to Slender Man, scrawled with slogans in all capital letters like NEVER ALONE and HE STILL SEES YOU, many of them deploying the “Operator Symbol,” a circle covered by an X, which is supposed to either fend off Slender Man or draw him near.

In Anissa’s account, Morgan proposed that they kill Bella to become proxies sometime around late December or early January. One senses in the background of Anissa’s version a chorus of derisive peers challenging their dedication to a fantasy character. “I didn’t want to do it,” she said. “But later, I didn’t want to leave Morgan all by herself out here, because I thought it would be cool to prove the skeptics wrong.” In her interview, Morgan speaks far less about Slender Man than Anissa does, and she characterizes Anissa as the architect of the plan to murder Bella. “She made it seem necessary, and I figured that if it was necessary, then I would,” Morgan said. In Anissa’s telling, it was Morgan with the vision. “We were going to be like lionesses chasing down a zebra,” Anissa told police.

For all its fantastical elements, their plan had the outlines of a familiar mean-girls plot, in which two new friends conspire to discard a third wheel they’ve outgrown or come to resent. (Anissa “always calls [Bella] a bitch,” Morgan told police. For her part, Morgan tormented Bella, who was terrified of Slender Man, sending her links to Creepypasta and warning her that Slender Man would get her as she slept.) According to someone familiar with the case, the relationship between Anissa and Morgan was not sexual, but it was in a way like an affair: dangerous, exciting, wrong. It became a total preoccupation that existed alongside the much more mundane aspects of being 12. “You have no idea,” Morgan told police about their plotting, “how difficult it was not to tell anyone.” She told police that she went through with the stabbing in part because “I didn’t want to make Anissa mad. It’s hard enough to make friends. I don’t want to lose someone over something like this.”

After the attack, as Bella crawled her way to help, Morgan and Anissa wandered: crossing train tracks, passing a cemetery, resting at a furniture store giving out lemonade. Morgan told Anissa she had a map in her head, but Anissa felt that they were lost. Like children who run away from home with precious belongings tied into bandannas, the girls were serious enough about their plan to have packed, but not enough to have brought anything of particular use. They had a couple of granola bars. They had some water bottles. Morgan was carrying one of her mother’s old purses, into which she had stashed the knife. Anissa had even brought along keepsakes in the form of some old family photos. “We were probably going to be spending the rest of our lives [with Slender],” she told police, “and I didn’t want to forget my family.” Here, Anissa begins to cry. “You know how distant family members and friends fade away with time.” Anissa had also left two messages on her cell phone, discovered after the fact. Written just days before the stabbing, one was like a will, bequeathing all her possessions to her parents. The other was an overwrought adieu, as though the murder in her mind were a suicide, too. “This is my final wish to those who care, do not grieve my absense, but remember me for who i was. I love and cherish you all and wouldn’t do you harm.”

As they walked and sang to each other, Morgan felt “surprisingly calm … I actually felt nothing.” Anissa, on the other hand, was super-scared: “I had a total nervous breakdown, and blamed Morgan for everything. I said, ‘You stabbed her. You wanted to do this.’ Morgan is not one to cry very often, but finally she just let go and started crying.”

Right after the attack, Morgan had made a terrible confession to Anissa. She had “kinda sorta” made a side deal with Slender, she told her friend: In private, telepathic conversations, Morgan promised Slender that if they failed to go through with the murder, then Slender could have his way with their families. Anissa fell apart again. “I said, ‘I’ve had enough of this. I want to call my mom. I want to go home.’ ”

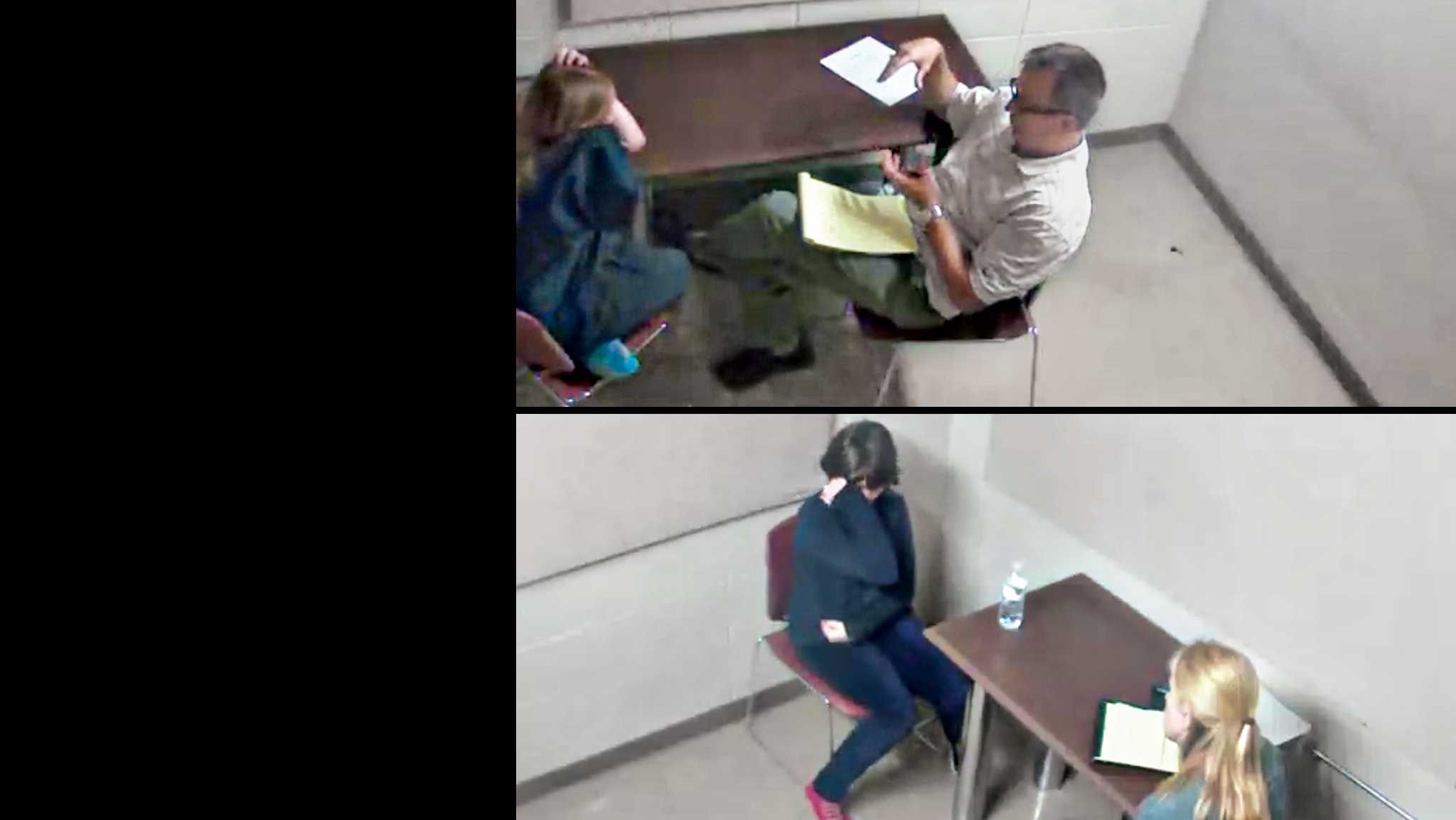

At the police station, the girls were put in separate, identical blank white rooms, furnished with nothing but one table and two chairs, for questioning. Mounted high on the wall of each room is a video camera, which the detectives, by and large, ignore. In the recordings, the girls are disheveled, articulate, 12. As the camera rolls, each girl obediently gives her hands to the bald and jocular forensics guy so he can scrape beneath their fingernails (“Looking forward to summer break?” he asks Anissa, like a dental hygienist); when they’re asked to disrobe so their clothes can be sent to the lab, the detectives steer the girls away from the lens; when they return to the frame, they’re wearing prison-issue scrubs several sizes too large. Morgan gets little disposable booties, too, like you get in the hospital, and she starts fiddling with them, until, on her left foot, most of her toes have pushed through. Anissa is barefoot. When the detective brings her two big gray blankets, she wraps one around her shoulders and coils the other around her ankles, making a fat covering for her feet.

Anissa spills. The detective questioning her, Michelle Trussoni, is gentle and motherly. Anissa is helpful, detail-oriented, and literal. She wants the detective to understand; she wants to do a good job. She needs tissues. She is shaking. She weeps more or less continuously. But she has a grasp on things — on who Slender Man is, on what Creepypasta is, on the exact route she and Morgan took out of town, on the last names of her relevant friends. You can sense her relief. One of the things she wants to make very clear is that Morgan did the stabbing, not her. She’s “too squeamish.” She says this over and over. She even gives the detectives a sort of redemption story: “Beforehand, I believed,” she told them about Slender Man. “Now I know it’s just teenagers who really like scaring people and making them believe false things.”

Morgan seems like she is from another planet. When the recording begins, she is sitting on a chair. Her hands are handcuffed behind her back, and she’s still got her coat on. The posture of her arms forces her body forward, but she cranes her face up, toward the camera, like a pale and curious turtle. Once the cuffs are off and the questioning begins, Morgan blames the whole thing on Anissa. Anissa told her to do it. Anissa made it seem necessary. She can’t remember, exactly, who held the knife. Of the two, Morgan was much more in the grip of the mythical power of Slender Man, but she barely mentions him until Detective Tom Casey, apparently receiving reports from the next room, begins to press the point.

Morgan pulls her bare arms inside her giant shirt; sometimes, she tucks her whole head in there, too. At one point, she asks Casey if she’ll rot in jail; at another, she says, “Please don’t cut off my head.” Morgan is also hostile. “Stabby stab stab stab,” probably the most-quoted phrase in the Slender Man canon, is prompted by her growing annoyance with the detective, who gently but firmly keeps asking her to describe the moment of violence again. “Are you trying to do this over and over again and see if I tell the story differently?” And then: “I have the right not to go into detail about it if I don’t want to.”

Near the end of their interview, Morgan is left alone with a container of takeout food. She approaches the Styrofoam box daintily, like a cat, and removes a single French fry, eating it in tiny nibbles. Slowly, she takes out another three, placing them in a small pile on the table. She eats the fries one by one, crouched in her chair. Once she’s done, she takes a lap of the small room, looking beneath the table and in the corners and touching invisible spots on the wall. Then she sits back down and removes a few more, holding one fry upright in one hand and her asthma inhaler in the other, like little dolls, and makes them dance.

Since May 31, 2014, the day of the attack, the girls have been living in a juvenile-detention facility. Their 14-month tenure makes Morgan and Anissa eminences here; for most kids, Washington County is a layover, a place where they spend a few days or weeks, awaiting trial after jacking cars or selling drugs or doing something stupid with a gang. Still, it’s an intimate place. In hearings, the same prison guard has testified on behalf of both girls. Anissa and Morgan are kept apart — separate living quarters, separate classrooms — but depending on the day, they will glimpse each other as they pass in the hall.

The judge in the case has ruled the girls mentally competent, their crime serious enough to be tried in an adult court. But that is a legal judgment, not a moral one, and each girl’s lawyers still plan to argue that on that Saturday morning last May, their clients were still, in every meaningful way, children — not wholly competent to think their actions through, and, as a result, not guilty. On August 21, the judge entered pleas of “not guilty” for both girls, though their lawyers may later revise that plea to reflect a claim of insanity (relevant especially in Morgan’s case). In any trial, Morgan’s lawyer will probably try to show that at the moment of violence, her schizophrenic client was in the grip of her illness. Anissa’s lawyers will likely argue that she was in the throes of a “shared” delusion, an immature thinker in thrall to a powerful friend. As her lawyer Maura McMahon argued at a hearing in May, “Was her behavior good that day? No. Should she have run away and summoned an adult? Certainly. But given what she was dealing with … she did what she could.”

In jail, Anissa has been a model inmate. Compliant, pleasant, an overachiever (she has done the seventh-grade history curriculum twice, and has elected to take a world-geography course), she persists in her “big sister” role with other inmates, though she made clear from the moment she was booked that she wanted nothing to do with Morgan. “She’s kind of like a stabilizing force with the other kids,” Gary Cross, one of Anissa’s teachers, told the court in May. “The mother hen or something.” Upon entering prison, each “juvenile,” as they’re called, is given a list of 39 rules — including no roughhousing, no gang talk, and no putting staples or comb teeth through piercing holes — and Anissa follows them to the letter. She has been reprimanded only a handful of times: for drawing on herself with colored pencil, for sitting on a table, for braiding another girl’s hair — and for swearing, which she did to fit in, she explained.

Anissa is also a mess. She seems unable to retrace her steps and fully understand how she got to this place. In July of last year, after threatening self-harm, Anissa was put on suicide watch and given a straitjacket. She occasionally complains of stomachaches, enough to keep her out of classes in jail. Last March, she fell to pieces after a bunch of girls started taunting her, calling her a “monster” and a “fucking bitch” for what she’d done. She started to cry and refused to leave her room, according to a jail administrator, saying, “That’s what I am, exactly what they had called me.”

For four months last fall, Morgan was transferred to the Winnebago Mental Health Institute, where she was put under 24-hour surveillance and diagnosed as schizophrenic. She has a “long history of auditory, visual, and tactile hallucinations,” Dr. Kenneth Casimir testified in June. Since the age of 3, she has been haunted by “vivid dreams which she wished she could change.” By third grade, “she was seeing images pop up on the wall in different colors.” Also, she could see and feel ghosts hugging her. Morgan was also diagnosed with “oppositional defiant disorder,” a tendency to be antisocial and break the rules. Casimir also found Morgan to be at continued risk for harming others. “If [Slender Man] told me to break into someone’s house and stab them, I would have to do it,” she told him.

In her police interview, Morgan is not quite willing, or able, to release Slender Man entirely to the realm of acknowledged fantasy — “It was weird. I felt no remorse … I still have this idea that it was necessary,” she tells the detective — and, in jail, Morgan seems to be unraveling further. According to testimony from guards and other people who have observed her, she is frequently seen in conversation with people who aren’t there. She eats her meals on her knees on the floor with her back to the door, and when someone unexpected comes to see her, she sometimes whirls around and make claws with her hands, like a cat. She regards the ants in her jail cell as her pets, feeding them off her meal tray; sometimes, she will take them to the rec room and throw them on other kids. She doesn’t talk much to the other children. She made a dollhouse with minute detail — a tiny CD player and tiny CDs and closets filled with clothes — entirely out of ripped and colored-in paper, because in prison you can’t have scissors. During her incarceration, Morgan had a falling-out with her father, ripping him out of all the family pictures in her cell; apparently, the fight was about his disrespect for her imaginary friends.

The September after the stabbing, Bella went back to school, and has done well, according to a family spokesman; she loves music and she’s had a few friends over for sleepovers at her house. Still, she and her family attend weekly therapy sessions, and when she grows up, she is expected to need plastic surgery. To that end, the Leutners have established a fund which accepts contributions online and benefits from the occasional fund-raiser, like a recent convocation organized by a female motorcycle club riding from Valparaiso, Indiana, to Waukesha. To date, donations amount to more than $250,000.

Morgan celebrated her 13th birthday in jail, and around that time she received a visit from Donna Joan Bennett, a social worker. It had been a year since Skateland, since dress-up, since she found herself in the Waukesha police station being questioned by a detective about the stabbing of her best friend. Her dinner tray before her, she spent the session rolling up pieces of bread and stirring them into her soup. When Bennett wished her a happy birthday, Morgan shrugged her off. It’s really no big deal, she said, “just one day closer to death.”

*This article appears in the August 24, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.