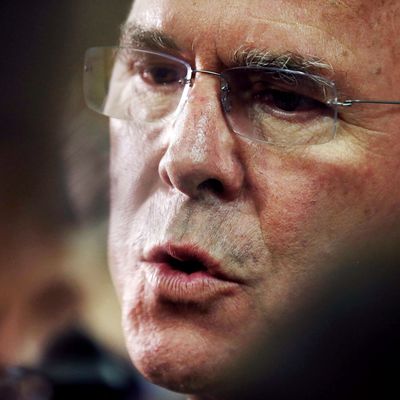

It has still been possible, late this summer, to catch Jeb Bush on a good day. At these times, his stiffness subsides and the dimensions of his empathy become apparent. His interest in policy seems deeper and his grasp of it more intuitive than that of the rest of the Republican contenders for president. His comparative centrism seems not just tactical but felt. And it seems like those $120 million in campaign contributions did not just accrue to him by the accident of his family name but also because he actually represented a possibility: that conservatism might offer not just a logic for screechy opposition to the country’s basic social direction, but a way of moving with it.

I happened to catch one of these good Bush days a week ago Wednesday, at an education-reform forum outside of Manchester, in which Bush and five of the other GOP candidates for president spent 40 minutes each telling war stories about their battles with the teachers unions and pontificating about the liberations that technology and market competition would bring to schools. Not a very hard topic and not a very tough crowd.

But Bush was simply better than the rest — better than Chris Christie and Bobby Jindal; better than the two other moderates he, improbably, is trailing in New Hampshire, John Kasich and Carly Fiorina; and better than Scott Walker, once and perhaps still his main competition for the nomination. Walker was genial where Bush was tense, underbriefed where Bush tended to bushwhack straight for the densest policy brush. Walker more or less waved his hands at the atmospherics of the summit: all of the worried education talk about the future of the American middle class and the testing prowess of fourth graders in Singapore. All this stress about achievement seemed a little overblown, Walker said. He wanted to push community college, to encourage sixth and seventh graders not just to dream of becoming doctors and lawyers but also “welders and IT technicians.” “There are great careers there,” he pointed out; increasingly, he said, the well-paying jobs were technical ones. Walker’s politics of combat is in service of a sublime social placidity, a kind of case against hopes and dreams: America, you just do you.

Bush took almost exactly the opposite line, a paternalistic horror that standards had so badly lapsed. Mitt Romney and Jeb Bush share roughly the same politics but almost exactly the same mien. Jeb Bush has none of his brother’s louche ease. Instead, he has Romney’s urgency and agitation, his occasional entitled cruelty, his inability to construct a public mask that is any different or better than the public one, his dispositional desire to measure up. When Campbell Brown (the host of the education summit) asked Bush to name a teacher who had inspired him and whose work helped shape his view of education, he named his sophomore-year Spanish teacher at Andover, a man from Spain named Angel Rubio, who insisted the tenth graders read Borges and Cervantes even as they struggled with the basic grammar. From this Bush came to understand, he told Brown, that what society owed everyone within it was high expectations. He told Brown, too, about his revulsion, as a candidate for governor, at seeing a high-school senior in an Orlando suburb prepping for the test he needed to pass to graduate and struggling with a question that asked how long a baseball game lasted if it started at 3 p.m. and ended at 4:30. When he claimed credit for raising standards in Florida sufficiently so that high-school graduates needed to pass an 11th-grade equivalency test rather than an eighth-grade equivalency test, he also expressed an almost yelping alarm that he had not been able to get the graduation standard to 12th grade. He referenced with feeling his brother’s great line from the 2000 campaign — the soft bigotry of low expectations. Listening, you could just about etch out the country as Jeb Bush saw it: a 300 million-person Andover of the mind.

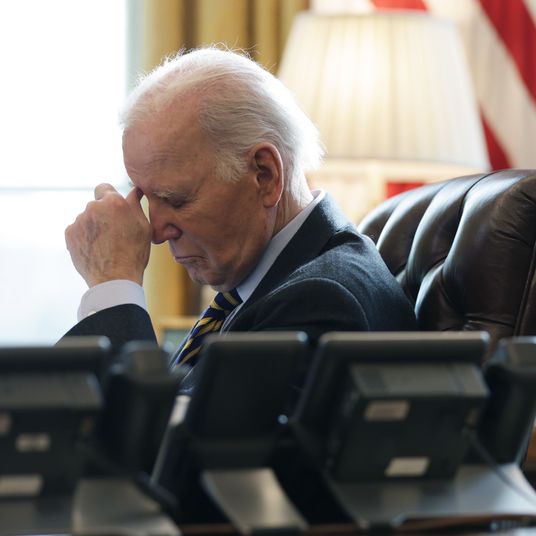

There haven’t been enough good days like this for Bush recently, and a campaign that started out with the exactness of eye surgery, prophylactically defusing a series of potential minor scandals, has grown more loose and uncertain, most alarmingly with Bush’s pointed pandering references to “anchor babies,” an episode in which he entirely abandoned his best self. Part of this is just the normal pattern of Republican primaries, in which cyclic enthusiasm for the wild-eyed recedes into a quieter preference for the Establishment figure. But it also could be that the party, in the long aftermath of the financial crisis, is no longer itself, that the structures of American politics (open primaries, fixed two-party system) have confined the energies that empowered nationalist third parties across Europe within the Republican Party, that the GOP has become a police-sketch version of itself and that no correction is bound to come — that Bush simply no longer fits.

During the Obama years, as the Republican Party’s populism has deepened, the conservative aim has been more explicitly to restore the past — to repeal, to roll back. But the populist surge has also served to complicate the Republican relationship with privilege. Entitlement for the Bushes and Romneys was personal, aristocratic, and could at its best beget a politics of noblesse oblige. But for Walker, Trump, and Cruz, the privilege that matters is the basic and plebian fact of being born American, and a hard line on immigration a way to protect it. One small part of what is at stake in this Gothic, fascinating Republican presidential primary is whether there is still room in the party for Bush’s aristocratic fervency, for the executive’s ethic of perpetual improvement, for the optimistic certainty that the future will be better than the past.